Strains in Nebraska and Kansas reflect impact of staff shortages in U.S. states’ correctional facilities

For years, states’ departments of corrections have struggled to fully staff their facilities — a phenomenon only exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

In Nebraska, the shortage has reached “crisis” levels.

According to the latest annual report published by the state Inspector General’s Office, there were a record-high 527 vacancies in June 2021, around 23 percent of total positions in the Nebraska Department of Correctional Services. The report also projected that by the end of calendar year 2021, the department will have lost 4,165 employees since 2015.

“Let’s face it, working in the correction system is tough work,” says Nebraska Sen. John McCollister, who serves as vice chair of The Council of State Governments’ Midwestern Legislative Conference Criminal Justice & Public Safety Committee.

“If there are viable alternatives to working in the corrections system, I think some people have opted to take less-stressful work.” (Nebraska’s unemployment rate in November was 1.8 percent, lowest in the nation.)

Added to the difficulty of the job is a deteriorating work culture, which Nebraska Inspector General Doug Koebernick says his office has found in recent surveys of correctional staff.

The office’s annual report, too, references anecdotal evidence of staff members suffering emotional breakdowns after working mandated overtimes, sometimes lasting 24 hours straight.

Last September, several current and former NDCS employees voiced their concerns to members of the Unicameral Legislature’s Judiciary Committee. According to Nebraska Public Media, the hearing lasted more than six hours.

In neighboring Kansas, years of staffing shortages have resulted in in-person visits being suspended indefinitely in one facility, and offenders spending increased time in their cells — sometimes 23 hours a day — at another.

Sarah LaFrenz, president of the Kansas Organization of State Employees, points to other consequences as well.

“We’ve had two, in less than a month, very serious staff assaults at one particular correctional facility,” she says.

“There are fewer people [working] in those living units, maintaining order and ensuring that things are going the way they’re supposed to. There are fewer people who are going to [cafeterias] to help [offenders] get their food or get their meds.”

“So it very much affects the people that live there, those who are incarcerated. And the safety of the people that work there is very much compromised.”

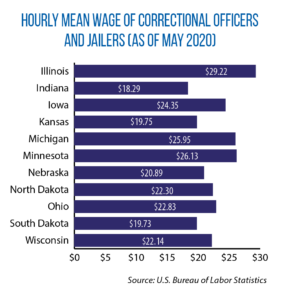

Will higher pay help?

The governors of Kansas and Nebraska have reached new deals with labor unions representing workers in their respective state correctional facilities.

In both states, the result will be considerably higher base wages and shift differential pay for overtime work.

In Nebraska, starting pay for a corporal corrections caseworker will jump by 40 percent, from $20 to about $28 an hour.

And a new deal with the Nebraska Association of Public Employees (which represents nurses, counselors, food-service staff and others who work in corrections facilities) includes $3-an-hour raises, increased overtime pay, and 2 percent cost-of-living adjustments for certain employees.

This isn’t the first time Nebraska has attempted to offer attractive financial incentives as a recruitment tool. In 2019, the state began offering $10,000 bonuses for new corporal hires at three of its most understaffed prisons.

According to the inspector general’s report, within two years, almost 60 percent of people who received these bonuses had left NDCS, including 79 employees who quit after being on the job for less than four months.

Additionally, although certain front-line security staff supervisors have recently seen increased pay to reflect their seniority, similar step-pay strategies have not occurred across the board, leading to ongoing wage compression — where subordinate employees eventually earn more than their supervisors, which, in turn, leads to more staff exits.

Despite past events, Koebernick is optimistic about the impact of the latest labor deals.

“It’s going to be very difficult for them personally to make that decision to leave just because they are getting paid such a significant amount higher than they were before,” he says, “and it’s going to be harder to find a comparable position with that kind of rate of pay within the community.”

Additionally, Koebernick is urging agency leadership and lawmakers alike to check in more frequently with correctional employees in order to assess complaints and staff morale.

McCollister also notes that broader legislative changes would help reduce correctional staff workloads.

“Sentencing reform, probation reform,” McCollister says, “those things need to happen to reduce the prison population.”