Surplus of ideas in unique budget year

Record-high reserves and big influx of federal aid have lawmakers considering new spending plans and tax cuts, but they also see need to prepare now for coming fiscal cliff

In his nine years as a legislator, Rep. Troy Waymaster says, he’s never experienced a budget situation even close to the one right now in Kansas: a projected surplus nearing $2.9 billion by year’s end and close to $4 billion by 2023.

But he’s also clear-eyed about what lies ahead in the not-so-distant future.

“There has just been this huge infusion of money from the federal government into the economy, and that’s what has precipitated our ending balances to be so high,” says Waymaster, chair of the House Appropriations Committee. “The federal government cannot continue to infuse that money. It’s going to stop. “So we’ve got to be prepared for when that fiscal cliff happens and our ending balances begin to dwindle.”

Pay off debts. Address Kansas’ unfunded liabilities in its retirement system for public employees. Build up a rainy day fund. Ensure any new spending or tax-cutting proposals can sustain budgetary ups and downs over the long term.

Those were some of the ideas and principles guiding Waymaster entering the 2022 legislative session. It’s a cautious approach that Josh Goodman of The Pew Charitable Trusts says he was seeing early in the year in other states as well.

“One thing that has been gratifying to me, at least, is as lawmakers talk about new investments — whether it’s in the form of spending or tax cuts — they’re also recognizing that a lot of this is temporary money, and that we need to prepare for this cliff when the federal aid expires and when state revenue returns to a normal level,” says Goodman, a senior officer for Pew’s State Fiscal Health program.

‘A lot of uncertainty’

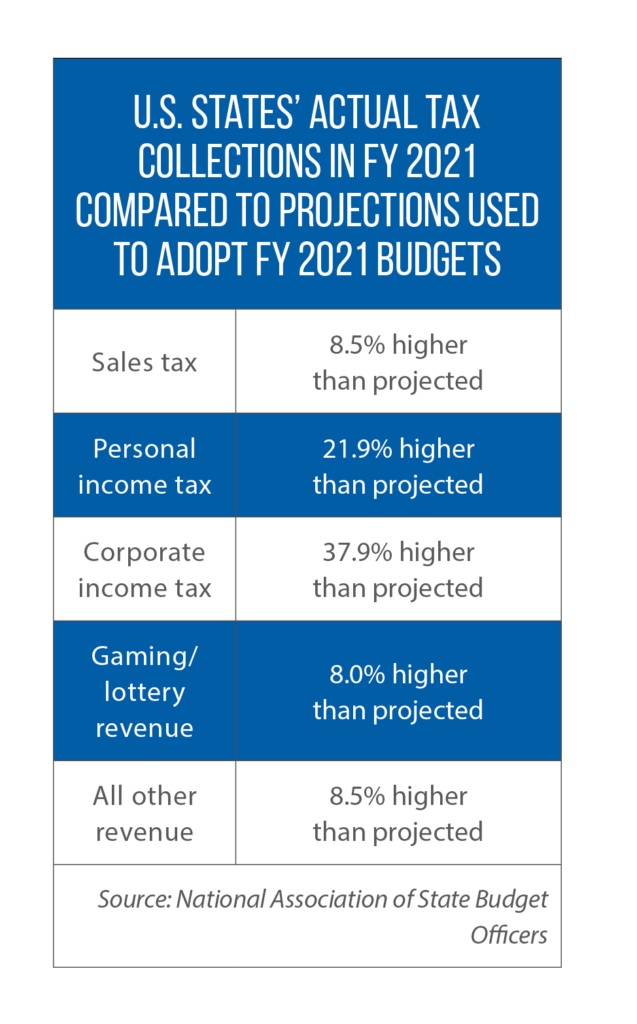

The last year has not been “normal” in terms of state finances. According to the National Association of State Budget Officers, states closed their books for FY 2021 with year-over-year growth of 14.5 percent. That was the highest annual increase in at least four decades. In comparison, NASBO data show, average annual revenue growth for U.S. states has been 5.4 percent.

“It’s an impressive amount of money that states are sitting on right now, not only to pay pandemic bills, but to make investments that they otherwise could never have afforded,” says Barb Rosewicz, project director for Pew’s State Fiscal Health program.

In Minnesota, the state’s most recent budget projections point to a surplus of $9.25 billion by the end of the current biennium.

“I’ve probably been through more deficits than surpluses as a legislator, but this year reminds me of a saying I heard a long time ago: In the legislature, you’re going to argue more when there’s a surplus than when there is a deficit,” says Minnesota Sen. Julie Rosen. That’s because everyone has ideas on what to do with the excess money, she adds.

Entering the legislative year, Rosen was envisioning a balanced approach: return some money to taxpayers; spend more in high-need areas such as public safety, mental health and financial support for frontline COVID-19 workers; get Minnesota’s unemployment trust fund out of debt and back on solid footing, and shore up the state’s long-term fiscal health.

“I would like us to look at paying off some of the responsibilities, some of the debt that we have — whether it’s our tobacco fund bonds or just our overall bonding debt,” says Rosen, chair of the Senate Finance Committee. “There are a lot of things we could start to pay down, which would really benefit the state.

“And we want to maintain that healthy budget surplus because with inflation and other things coming down the pipeline, I think there is a lot of uncertainty right now [about the future].”

Value of a long-term budget outlook

Lucy Dadayan, a senior research associate with the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center, says there are many reasons for states to prepare now for the bursting of what she calls a “fiscal bubble.”

For one, her research shows a “huge gap” in recent state revenue growth compared to increases in GDP, with the former significantly outpacing the latter. Such a disparity is atypical, Dadayan says, and will not continue.

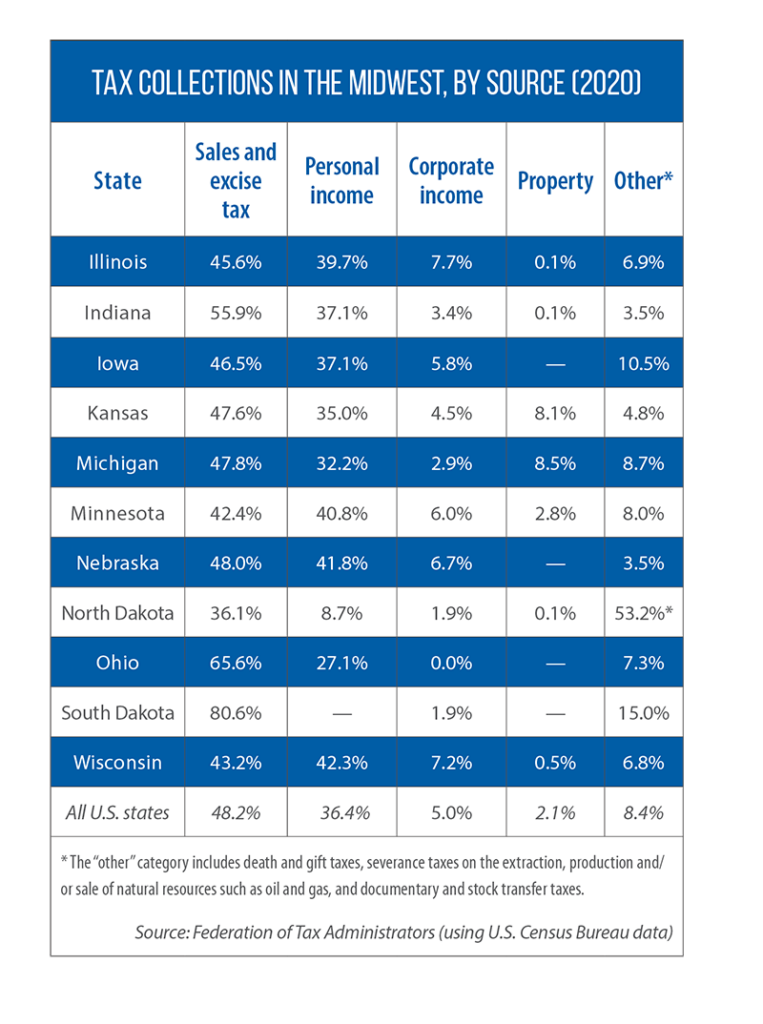

Second, the pandemic temporarily changed consumer habits, with a shift to more spending on goods (subject to the sales tax) than services (often not taxed in many states). A return to the longer-term trend — more spending on services, less on goods — is coming and will cause a negative impact on sales tax collections, she says.

Third, the additional federal dollars supporting the overall economy, and states in particular, will be gone. Money from the American Rescue Plan Act’s (ARPA) State Fiscal Recovery Fund must be appropriated by the end of 2024 and spent by the end of 2026. In a November 2021 study, the Center on Budget Policy and Priorities noted that of the nearly $200 billion set aside in ARPA for states, more than half of it already had been allocated by the nation’s governors and state legislatures.

The most common uses of ARPA dollars thus far have been: 1) the replacement of lost state revenue due to the pandemic (23 percent of total state allocations); 2) replenishing unemployment trust funds and improving UI systems (15 percent); 3) human services (14 percent); 4) economic development (10 percent); and 5) broadband access and expansion (8 percent).

“I am worried that, three, four years down the road — or even less time than that — we are going to be seeing state revenue growth declining, and maybe even negative growth,” Dadayan says.

According to Goodman, to plan for volatility and uncertainty, states need to use data and budget projections that look more than only one or two years out.

“I think three years would sort of be a minimum, and we see some states looking five years, sometimes even 10 years out,” he says. “The right length really depends in part on when things will change. So let’s say a state had a major tax that was set to expire in six years. You wouldn’t want to only look five years out and ignore what’s going to happen in that sixth year and beyond.

“And so right now, in particular, states should be thinking about their budget picture after the federal relief is spent or expires.”

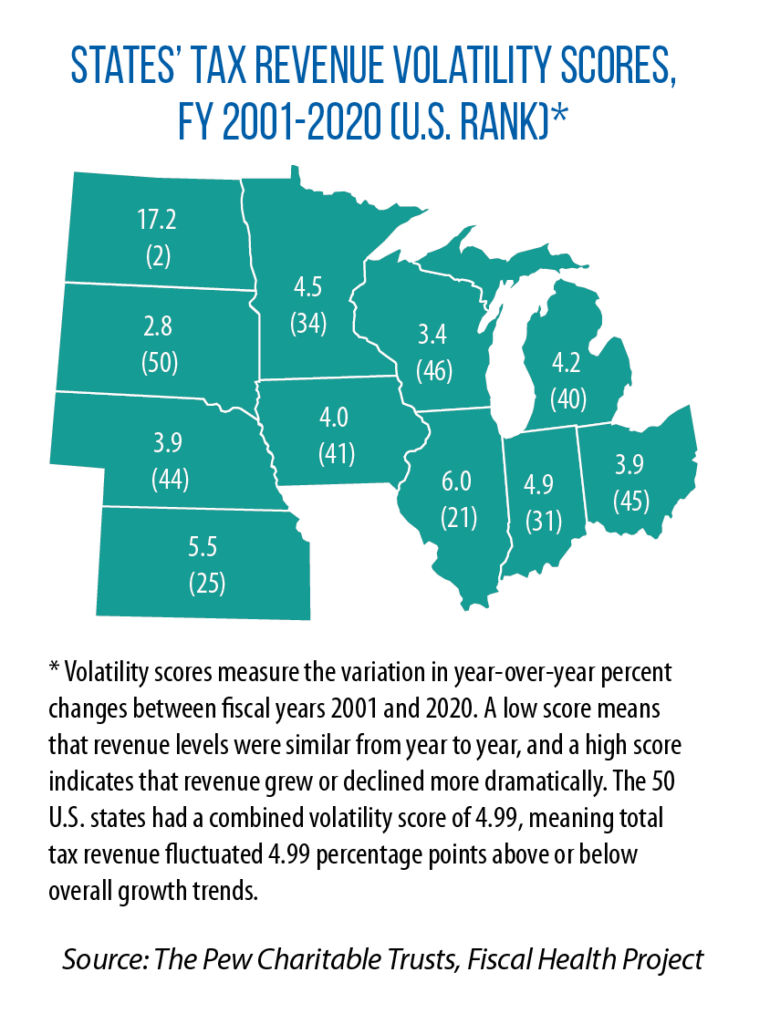

Likewise, looking back at the volatility of state revenues can help fiscal leaders make sound long-term budgeting decisions. Over the past 20 years, Pew research shows, the 50 U.S. states had a combined volatility score of 4.99, meaning total tax revenue fluctuated 4.99 percentage points above or below overall growth trends.

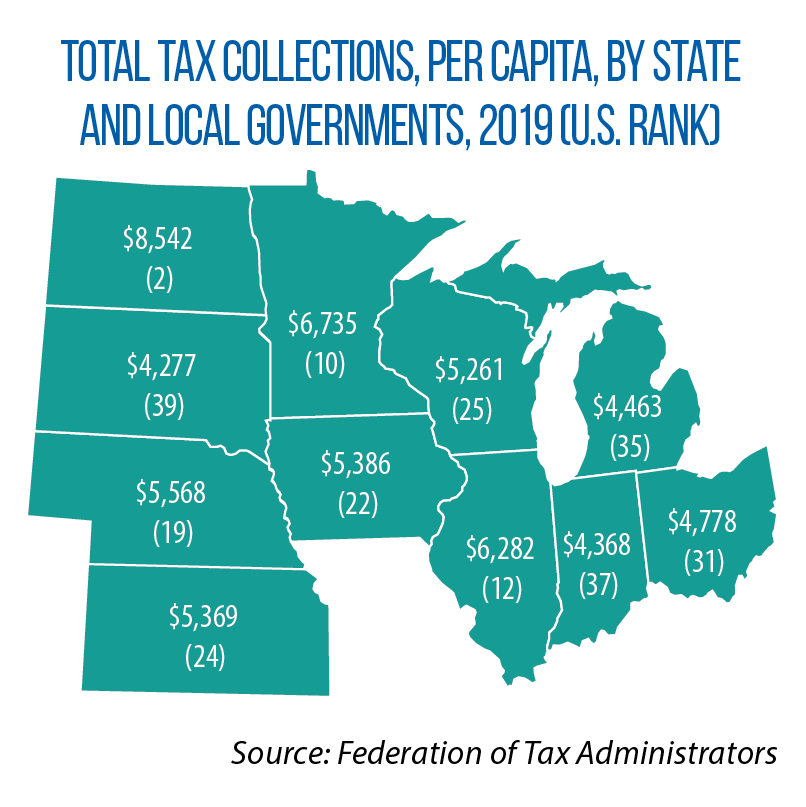

In the Midwest, the volatility scores ranged from a high of 17.2 in North Dakota (due to its reliance on an oil and gas tax, a turbulent revenue source) to a low of 2.8 in South Dakota (the state has no income tax and relies heavily on the sales tax, a relatively stable revenue source).

“By studying volatility, policymakers can better determine their own budgetary risk and put in place evidence-based savings strategies that harness tax growth in good years to cushion the lean years,” Pew notes.

Flexibility and opportunity in 2022

This is undoubtedly one of those “good years” for states, and there is excitement about some unprecedented opportunities. In Minnesota, every even-numbered year is known as a “bonding” year — a bill is passed by the Legislature and signed by the governor to borrow money in order to issue bonds for capital investment projects.

“With the kind of budget surplus we have, we have more flexibility in what we could bond for to help our communities, especially some of those that have been traditionally marginalized or under-invested in,” says Rep. Fue Lee, chair of the House Capital Investment Committee.

For example, he says, many communities are in need of more housing, educational and occupational services for young people, and job training in growing sectors such as clean energy. According to Lue, because of the state’s strong fiscal situation, general-fund dollars could be used for one-time investments in these kinds of community assets, on top of whatever is included in a final bonding bill.

In addition, an estimated $7.3 billion is coming to Minnesota as a result of passage of the Infrastructure Investment and Job Act. That law prioritizes spending on states’ transportation, water, energy and broadband infrastructures, thus freeing up more state bonding dollars for capital projects related to higher education or workforce development, Lee says. That juggling of state and newly available federal dollars also has been part of discussions in Kansas, Waymaster says.

“Part of what we tried to communicate early on with our [legislative] budget chairs was that as you go through all of the budgets for the different agencies and departments for the state, and as you get requests for revenue enhancements, think about whether those enhancements would qualify under ARPA rather than being paid through the general fund,” he says.

There is, of course, another option being considered by state policymakers during this exceptionally strong fiscal period — cutting taxes. Numerous proposals had been introduced early in 2022, including several in the Midwest, to lower corporate and income tax rates.

“We want to reduce taxes. There’s no question about that, but we want to do it in a responsible and strategic manner,” Waymaster says about the outlook in Kansas. “I came here to the Legislature in 2013 and lived through the budget issues that we had because of a tax plan that had passed the year before. That plan was just too aggressive.

“Today, it’s very easy to look at the balances that we have in fiscal years 2022 and 2023 and say, ‘Let’s reduce taxes.’ But at the same time, this is not going to last forever. And if we are too aggressive, then we’ll find ourselves in a deficit.”