With local jails overcrowded and lacking treatment options, Indiana gives judges discretion to send low-level offenders to state prisons

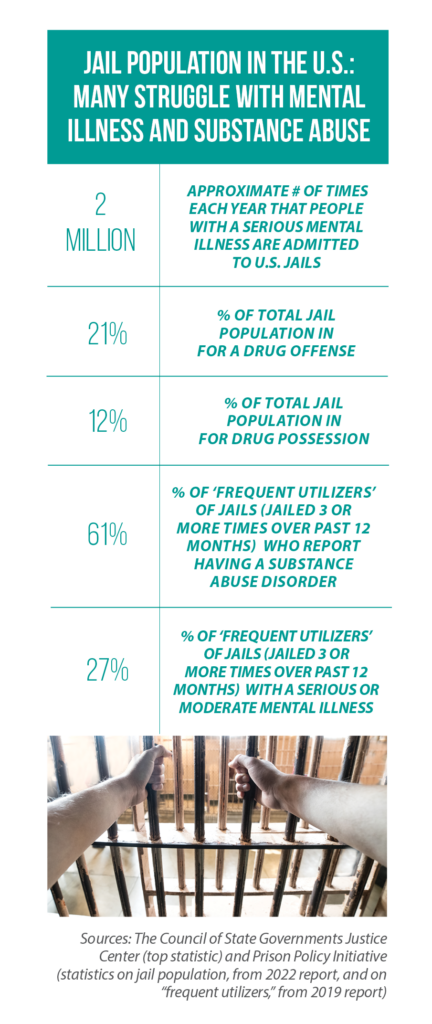

In Indiana, as in states across the country, a significant number of the people who commit low-level felonies suffer from drug addictions and/or mental health disorders.

In recent years, these Level 6 offenders have mostly been sent to local jails across Indiana.

The problem: Many of the jails are overcrowded and not equipped to provide treatment services. Without a path to recovery, the result can be high rates of recidivism.

In response, the Indiana General Assembly passed HB 1004. As a result, starting in July, judges will have the discretion to place Level 6 offenders in state prisons, which have a greater capacity to provide counseling and treatment services.

This policy shift will give individuals a “better chance of recovery” and “help them stay out of the criminal justice system,” Indiana Rep. Randy Frye, the author of HB 1004, said in a statement after the bill’s passage.

Despite the proposal receiving overwhelming bipartisan support, some legislators say the need for HB 1004 reflects a policy shortcoming: inadequate support for local programs that treat drug and mental health issues and reduce recidivism.

“We have to acknowledge that this bill is kind of a recognition of [our] failure,” Rep. Matt Pierce, who voted for HB 1004, said during a committee hearing earlier this year.

Local Needs Not Always Met

Back in 2013, the Indiana General Assembly passed comprehensive legislation (HB 1006) overhauling the state’s criminal code.

In part, the revisions reflected new guiding principles on how the justice system should treat low-level offenders struggling with addiction and mental illness.

“The whole premise was we’re going to essentially lower these drug sentences, get rid of mandatory minimums,” Pierce says. “Shift the system away from warehousing people and focus more on getting them to treatment.”

As part of this new approach, legislators changed how Level 6 offenders would be confined — in local jails rather than state prisons.

Soon after the criminal justice overhaul, too, pilot programs were established to evaluate the effectiveness of pre- and post-incarceration treatment services, with a particular focus on local care.

One of those services still in operation is Recovery Works.

Through the program, criminal justice-involved individuals who don’t have health insurance are connected with certified mental health and addiction treatment providers. The state then provides vouchers to these providers.

As part of a 2018 study, Indiana University researchers analyzed how Recovery Works has impacted recidivism. Its findings:

- Among participants who had never been incarcerated, 93.4 percent remained out of a correctional facility one year following their treatment.

- For participants who had previously spent time locked up, 90.2 percent remained free.

- Two years after treatment under the program, 87 percent of never-incarcerated participants and 79.1 percent of previously incarcerated participants had remained free.

What’s needed, Pierce says, is to increase the reach of treatment programs such as Recovery Works.

Instead, since passage of the 2013 law, the legislature has failed to consistently fund local treatment services statewide — despite evidence of their benefits, Pierce says.

“Making sure that every single county — either working on its own or with other counties around it in a regional way — would have that mental health facility, would have that drug treatment facility, would have the counselors and the mental health professionals that are needed,” Pierce said this year on the House floor.

“That was on us to do, and we’ve never done it.”

He believes this failure has contributed to jail overcrowding and recidivism.

Closer to Treatment, but Farther From Home

One concern with HB 1004 is that it will place some low-level offenders in a facility far from their loved ones.

“Having a support system, knowing that people are willing to come and see you … it has a tremendous effect on an individual that’s trying to get [his or her] life together,” says Sen. Rodney Pol, a former public defender.

He adds that certain DOC treatment programs like drug therapy have long waiting lists and “are designed for long-term engagement.”

“So the benefits of these programs [for Level 6 offenders] are probably going to be slim to nothing,” Pol says.

He proposed an amendment to HB 1004 that would have required consent from certain Level 6 offenders (those with a sentence of less than a year) before placement in a state Department of Corrections facility, rather than a county jail. That amendment was rejected.

__________________________________

Treating substance abuse and mental Illness in criminal justice populations: Two examples from the Midwest

Positive results seen from Minnesota’s Alternatives to Incarceration Pilot Project

Under a state-funded pilot project, one county in the Twin Cities metropolitan area launched a community-based strategy for non-violent offenders in need of treatment for substance abuse.

Traditionally, these offenders would have been sent to prison for technical violations. Instead, they were assigned a specialized probation officer and provided other community-based resources.

“[County officials] offered housing when they needed it, they did intensive group/individual therapy, they did a whole chemical dependency treatment modality right

there on site,” says Minnesota Rep. Marion O’Neill, a proponent of the 2017 legislation that first created the Alternatives to Incarceration grant.

Close to 90 percent of recent participants in this $160,000 incarceration-alternative treatment program have remained out of lockup. According to O’Neill, many of the people selected for the initial pilot study — nonviolent parolees at risk of reincarceration due to technical violations — would not otherwise have received treatment in prison due to their short sentences. The program has been expanded to two additional counties.

Kansas helps counties ‘step up’ efforts to reduce number of people with mental illness in jail

Last year, Kansas became the second U.S. state to open a Stepping Up Technical Assistance Center that helps counties reduce the prevalence of people with a serious mental illness in jails. Along with providing baseline data on the number of jail inmates with mental illnesses and substance use disorders, the center helps counties set reduction targets, measure progress, and develop evidence-based strategies and programs.

the prevalence of people with a serious mental illness in jails. Along with providing baseline data on the number of jail inmates with mental illnesses and substance use disorders, the center helps counties set reduction targets, measure progress, and develop evidence-based strategies and programs.

Stepping Up is a national initiative of The Council of State Governments Justice Center, the National Association of Counties and the American Psychiatric Association Foundation.

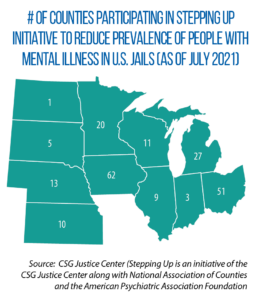

Its goal: rally counties to achieve a measurable reduction in the number of people in jail who have mental illnesses. As of July 2021, more than 200 counties in the Midwest were participating (see map).

Since that time, Iowa, Michigan and Wisconsin added one new Stepping Up county, each; and Kansas and Ohio expanded by two counties.