Housing shortages in rural areas are stifling growth, causing states to adopt new targeted incentives

In the small, north-central Kansas town of Stockton, more than 100 jobs are open.

The number of available places for prospective workers and their families to live?

Two, Kansas Sen. Rob Olson says.

Two, Kansas Sen. Rob Olson says.

“And we have [other] cities that are busing in 200 people to work because there is no available housing,” he adds.

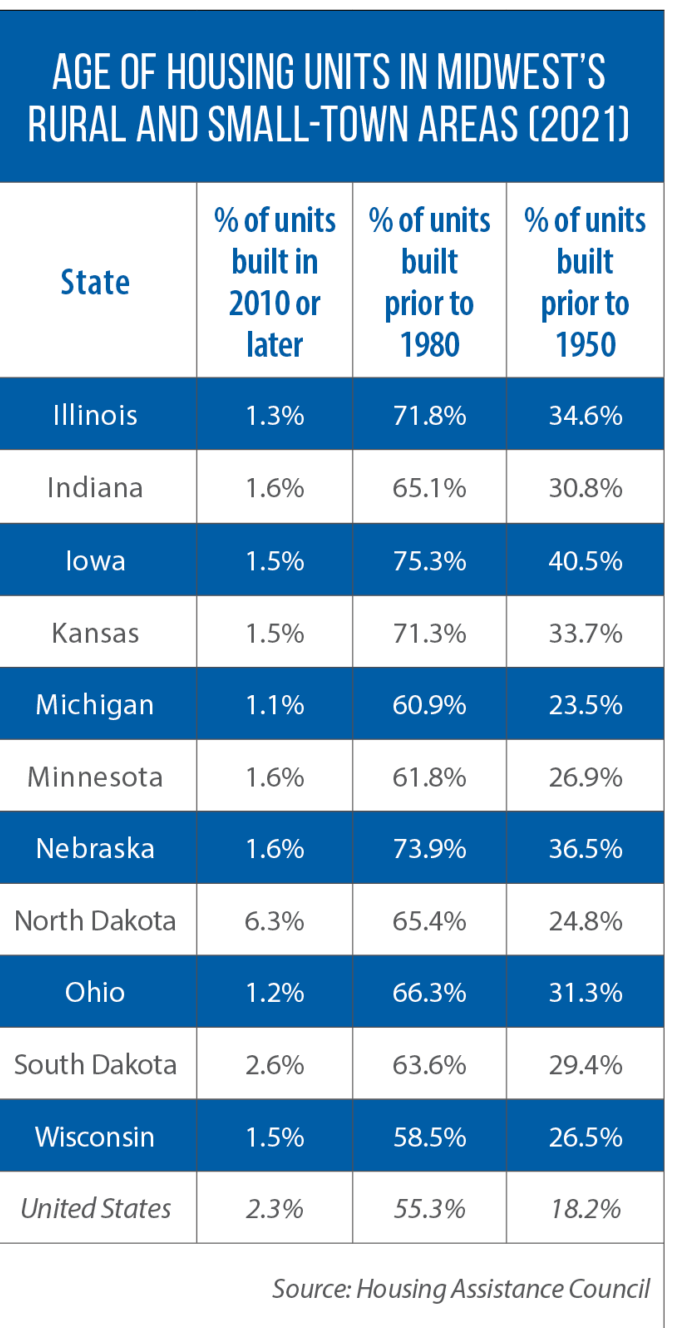

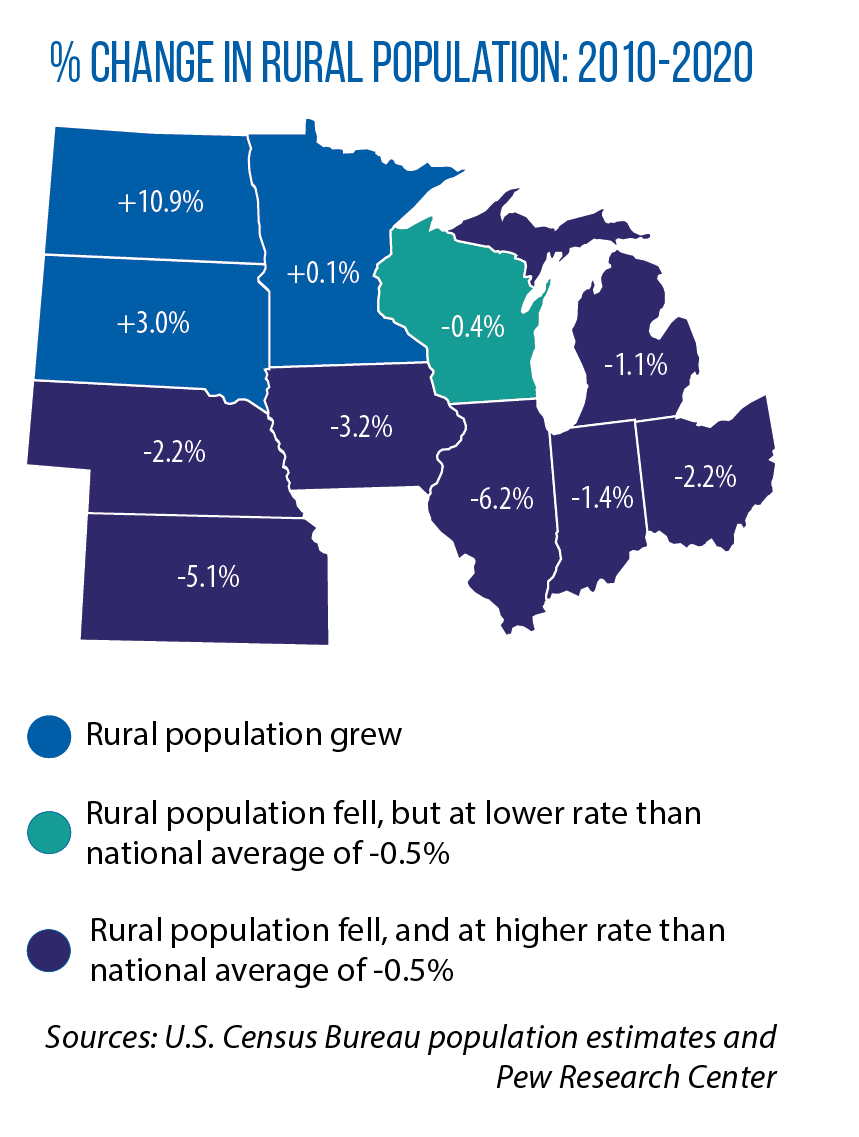

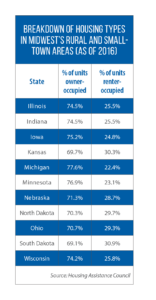

Many rural areas have been disproportionately impacted by a widespread lack of affordable housing. Factors include a housing stock that is aging and in decline, higher new-construction costs compared to urban and suburban areas, and appraisal values that oftentimes fall below the price of building a new home or fixing an existing one.

“When you have a small community that doesn’t have the proper housing, and you have businesses that want to grow or expand or move there, that’s a missed opportunity,” Olson says.

Through a mix of new income tax credits, loan guarantees and state grants, Olson and other Kansas legislators took sweeping actions this legislative session to jump-start rural housing development.

Kansas invests in new tax credits, loan guarantee

With this year’s passage of HB 2237, Kansas will begin funding an income tax credit program for developers who invest in the construction of affordable housing in smaller-populated counties:

- up to $35,000 in tax credits for each new housing unit in counties with fewer than 8,000 people;

- up to $32,000 for each new housing unit in counties with 8,000 to 25,000 people;

- up to $30,000 for each new housing unit in counties with between 25,001 and 75,000 people.

This approach, which Olson likens to his previous legislative work on angel-investor tax credits to spur business development, got bipartisan support in the Republican-led Legislature and the backing of Democratic Gov. Laura Kelly. Various stakeholders (real estate agents, bankers, mobile-home groups, the Farm Bureau, etc.) also got behind the proposal.

“We need to get more funding in the rural parts of the state,” says Olson, who, as chair of the Senate Federal and State Affairs Committee, played a lead role in this year’s legislative efforts.

Under the same new law, a total of $2 million in loan guarantees will go to projects that build new homes or rehabilitate existing ones in Kansas’ smallest counties (fewer than 10,000 residents). The guarantee, capped at $100,000 per home, is an attempt to address the problem of construction costs sometimes coming in higher than the appraised value of homes.

A second new law in Kansas, SB 267, directs more dollars to a program that assists local communities looking to spur the construction of moderate-income, workforce housing — whether that be multi-family rental units or single-family homes.

Prior to this year, Olson says, Kansas was providing $2 million in assistance.

“We were barely scratching the surface [of needs],” Olson says. “This year, we added $20 million, putting in enough money to fund it for about three to four years.”

The program targets help for communities of fewer than 60,000 residents; the new dollars come from the state’s allocation of American Rescue Plan Act funds. Separately, SB 267 also designated $20 million in general-fund dollars to establish a Rural House Development Revolving Loan Program. Loans or grants will go to rural communities for infrastructure projects related to moderate- and low-income housing development.

The program targets help for communities of fewer than 60,000 residents; the new dollars come from the state’s allocation of American Rescue Plan Act funds. Separately, SB 267 also designated $20 million in general-fund dollars to establish a Rural House Development Revolving Loan Program. Loans or grants will go to rural communities for infrastructure projects related to moderate- and low-income housing development.

“It’s going to take four or five years to really start to see the change, but it’s going to be there,” Olson says. “You’ll see growth and expansion.”

Olson himself represents Olathe, a suburb of Kansas City that is among the top five largest cities in the state. But he believes a boost in rural activity will help the entire state.

“The larger communities are doing everything that we can, but we are not using the full potential of the rural parts of our state,” he says. “We have opportunities for growth.”

Nebraska extends state-local housing partnership

Lawmakers in neighboring Nebraska also prioritized rural housing this session, approving a measure (LB 1069) that extends and expands an existing state program.

As in Kansas, previous efforts in Nebraska have showed signs of success, but not on a scale large enough to stem a housing crisis.

According to the University of Nebraska-Lincoln’s Department of Agricultural Economics, the state’s majority of non-metropolitan housing stock is more than 50 years old.

And more recent economic trends have made it more difficult to add housing stock, says Sen. Matt Williams, the sponsor of LB 1069. “We have seen increased building costs, supply-chain delays, and fewer contractors — [all] amplifying the problem,” he says.

Further, Williams says, Nebraska’s lack of workforce housing is intensifying the state’s ongoing workforce shortage.

As originally enacted in 2017, the Rural Workforce Housing Investment Act created a $7 million grant fund, which resulted in a $110 million investment in rural workforce housing and more than 800 housing units.

Two years ago, the state appropriated another $10 million in general funds for a second round of grants.

The program was set to expire at the end of this year. LB 1069 extends the program for the next five years with an additional $40 million in state funds. With this money, the state awards grants to nonprofit development organizations for the construction of workforce housing in counties with fewer than 100,000 people. These grants aim to mitigate the financial risk associated with the high cost of building in rural areas.

Under the 2022 law, the state is increasing the maximum allowable costs for grant-eligible projects — up to $325,000 for an owner-occupied housing unit (from $275,000) and up to $250,000 for rental housing units (from $200,000).

Additionally, lawmakers removed a cap on the amount that a nonprofit organization can receive; instead of $2 million, the limit will be determined by the state Department of Economic Development. Lastly, the local match to receive state funds was relaxed, from 100 percent to 50 percent.

For Williams, one of the program’s most promising aspects is that it’s built to last — because of the type of funding mechanism typically being used at the local level to meet the state’s matching requirements.

“Most are using a revolving-fund arrangement so the local programs keep growing,” he explains. “It’s the gift that keeps giving.”