Farm economy has outpaced expectations, but high input costs and labor shortages persist as problems

With the caveat that “agriculture issues can change quickly,” a leading economist told the Midwest’s legislators in July that conditions in one of the region’s most important industry sectors point to continued growth — both for farmers and the states that rely on the tax revenue.

“Right now the ag economy remains strong, supported by high prices and a robust domestic and international demand for U.S. farm products,” Cortney Cowley, a senior economist for the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, said in July during a session led by the Midwestern Legislative Conference Agriculture & Natural Resources Committee.

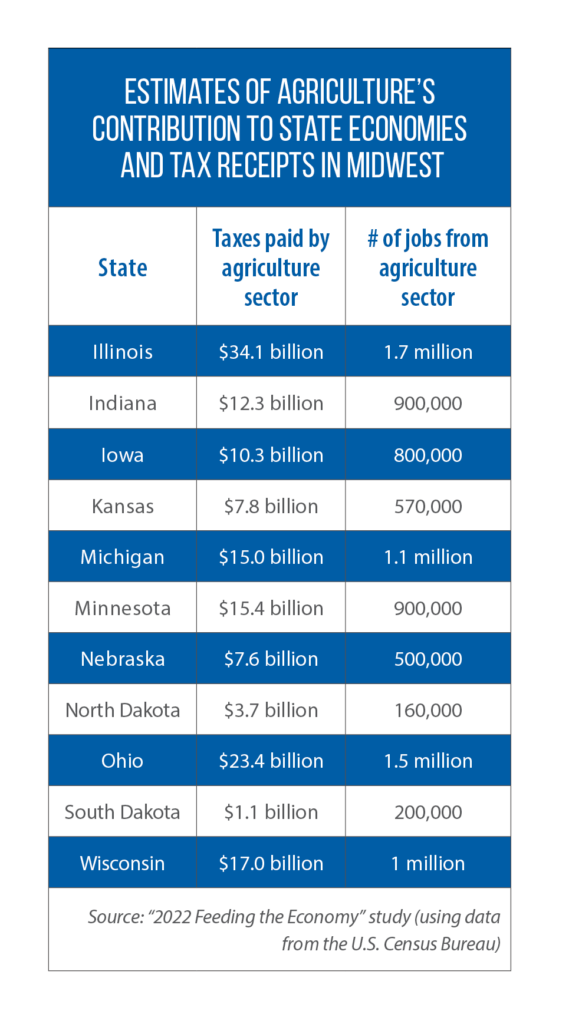

That is good news for the Midwest, where the health of agriculture affects entire state economies: In 2020, for instance, the industry supported 9 million jobs in this 11-state region, while generating close to $150 million in tax revenue.

It has been a tumultuous, yet often unexpectedly prosperous period in U.S. agriculture. At the end of 2019, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, many forecasters were predicting the continuation of a recent decline in the agriculture economy in 2020.

Then a global pandemic disrupted the entire food production chain. That year, though, farm prices bounced back quickly for most commodities, and when combined with pandemic relief from the federal government, 2020 turned out to be a strong income year for most agriculture producers.

One outlier has been the cattle industry.

“That sector is still struggling, and cattle prices have been slow to recover,” Cortney said.

When COVID-19 hit, a large portion of the animal processing workforce got sick; at one point, as many as 500,000 cattle were awaiting processing. It was a buyers’ market, and live cattle prices dropped. On the consumer side, meanwhile, a store-level shortage of beef occurred, causing retail prices to skyrocket.

These factors resulted in a large spread between low cattle prices and high prices at the grocery store. Cowley explained that this gap is continuing because many people who work on the cutting floor at animal processing facilities did not come back to the labor force after leaving due to COVID.

Labor shortages on the cutting floor are keeping processing numbers down, she said. Droughts also have hit many cattle-raising areas, and producers are dealing with high (and rising) input costs, particularly for feed. As a result, some producers are liquidating herds, and overall, the number of beef cows in the United States has fallen — a drop of 2 percent in July 2022 compared to a year ago.

This is the fourth straight year of smaller beef cow numbers, with the biggest decreases in heifer and cow inventories. Higher cattle prices should be coming soon as a result of this downward trend.

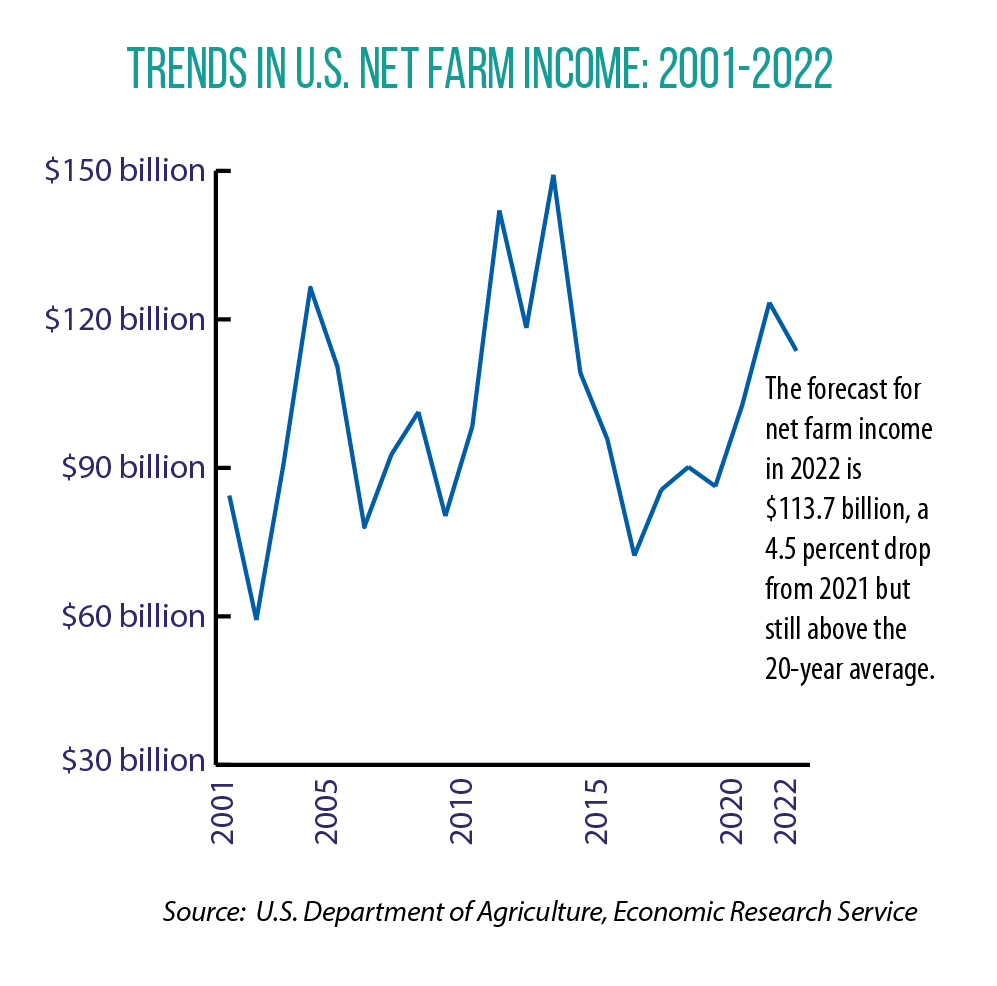

Across the agriculture sector, net farm income, a broad measure of profits, is expected to drop 4.5 percent this year compared to 2021 numbers — down from $123.4 billion to $113.7 billion, with this year’s figure still being high relative to most recent years and above the 20-year average.

In part, farmers have been using their increased income to pay off loans, with rates of farm loan delinquencies decreasing and loan repayment rates improving.

According to Cowley, just as supply chains in the farm sector were recovering from the pandemic, the war in Ukraine, labor challenges and the weather have impacted agriculture producers this summer. Because Russia and Ukraine account for a large share of the global production and export of grain and oil, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine caused historical increases in the price of oil and wheat similar to that seen during the Dust Bowl and the 1974 oil embargo.

The invasion caused broad disruptions in global commodity markets and large price increases, the latter exacerbated by already low inventories.

Markets have been dropping slowly, Cowley said, but higher commodity prices will continue to be supported by record-high exports through the remainder of the year.

For farmers, one concern continues to be a rapid rise in production costs, along with uncertainty about where input prices are headed. Right now, increases in input costs — particularly fertilizers, which are made from fossil fuels — are far outpacing rises in food prices. Between 2020 and 2022, the U.S. Department of Agriculture estimates that total production expenses will increase by more than 20 percent. This is leaving many farmers, particularly small and medium-sized producers, to question their ability to just break even this year, despite high commodity prices.

Cowley, in response to questions from legislators about how to help producers, said that states should look to increase access to credit and focus on strategies to ease the labor shortage.