In Minnesota and elsewhere, high-impact tutoring is making a difference in student achievement

For families with the financial means, tutoring often is the intervention of choice to help a child catch up or get ahead in school.

About $42 billion is spent on it in a single year, Wendy Wallace noted in July as part of a presentation to the Midwestern Legislative Conference Education Committee.

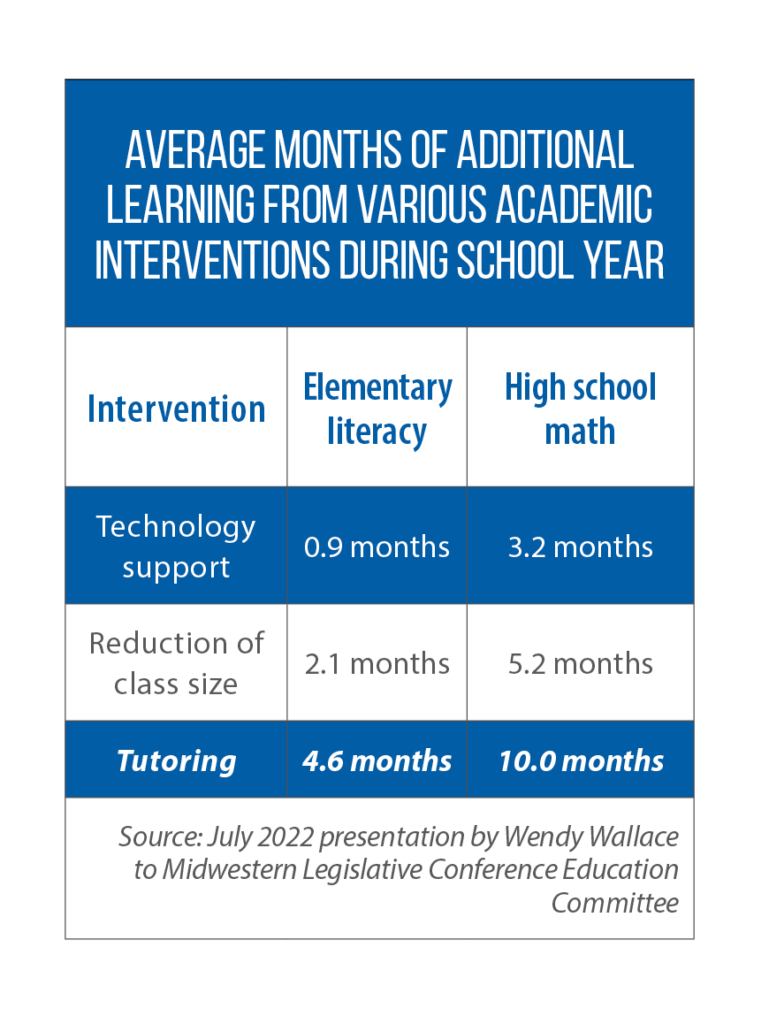

“[It’s] more effective than any other kind of academic intervention that researchers have found,” she added, comparing it to practices such as class-size reductions and technology supports. “The effects are shown across grade levels and subject areas, and range from a half a year to more than a year of learning [growth] over one year of academic tutoring.”

Often, though, the child who needs the tutoring the most — one at risk of falling behind and failing academically — does not receive additional supports. The goal of groups such as the National Student Support Accelerator, a project of Brown University’s Annenberg Institute for School Reform where Wallace works: Ensure every student has access to high-quality, high-impact tutoring.

Perhaps more than ever before, Wallace said, states have the opportunity to overcome the obstacles that traditionally have blocked the expansion of tutoring in their K-12 systems.

Schools have become more open to scheduling changes, and unprecedented amounts of federal assistance are available (via the American Rescue Plan Act). In addition, education leaders now have information on the essential elements of a high-impact tutoring program.

In the “No Child Left Behind” era of education policy, many students were offered, and participated in, government-backed tutoring initiatives. The problem was a lack of quality, Wallace said, causing the impact on student achievement to be “close to zero.”

What works?

Many of the essential elements can be found in long-running, successful programs run by ServeMinnesota, which oversees all AmeriCorps programs in that state. Through the organization’s early-learning, reading and math corps, tutors are embedded in schools across Minnesota.

People of all ages and backgrounds serve, Lindsay Dolce, chief advancement officer for ServeMinnesota, said to legislators.

“A lot of our tutors have never spent time in school and don’t have an education background, but they’re passionate about serving their community,” she added. “They want to give something back.”

Each tutor receives intensive, week-long training before ever stepping foot in a classroom. Then, he or she gets ongoing training and feedback, including from a staff person in the school building and from a “coaching specialist” at ServeMinnesota. Tutors also have access to high-quality materials and “scripts” to guide instruction.

Through the Reading Corps, students in kindergarten to third grade get 20 minutes of tutoring every school day. Math Corps provides a total of 90 minutes of tutoring each week to students in grades four through seven.

ServeMinnesota has expanded the reach of these tutoring programs, partnering with more schools in Minnesota while also spreading to states such as Iowa, Michigan, North Dakota and Wisconsin.

North Dakota Sen. Kyle Davison said the program has proven to be a “game changer” in parts of his state.

“We look at the kids on the bubble [of academic success or failure] and try to help them with this program,” he said. “One of the strengths of AmeriCorps is that these volunteers want to be in your schools, and the effect of a student’s relationship with that adult in that school every day, for 20 minutes [of tutoring], is just incredible.”

In Minnesota, the Legislature has gradually increased appropriations for these tutoring programs. (Most of the funding comes from federal AmeriCorps dollars; private donations help as well.)

Across the country, Wallace said, there has been an uptick in state support for high-quality tutoring — in the form of new grant programs and matching funds for schools. In addition, a handful of states now have laws defining “high-impact tutoring” and/or requiring that certain students have access to it.

Other options for states include training tutors that can be deployed in the schools, or bringing more college students into the classroom through new partnerships between K-12 and postsecondary systems.