Decades of groundwater depletion mean hard choices ahead for states

During expert-led session at Midwestern Legislative Conference Annual Meeting, lawmakers explore policy options to ensure water doesn’t run out for future generations of farmers, communities

On a recent visit to the western Kansas town of Garden City, Burke Griggs asked local leaders a question that may have first sounded like a joke. “Where do you plan on moving Garden City in 50 years?” asked Griggs, a leading expert on water law.

He was deadly serious, though, about a problem that the Washburn School of Law professor says a growing number of communities will face in the coming years and decades without shifts in how the state manages, allocates and conserves its resources, particularly groundwater.

“You can’t think about a hundred years of urban planning on 40 years of water,” he said. “And it’s a problem that’s facing the Great Plains as a whole. If we don’t start refocusing our water policy around our public, we’re going to be in serious trouble.”

Kansas Rep. Ron Highland, who joined Griggs as a panelist in July at the Midwestern Legislative Conference Annual Meeting, echoed those concerns.

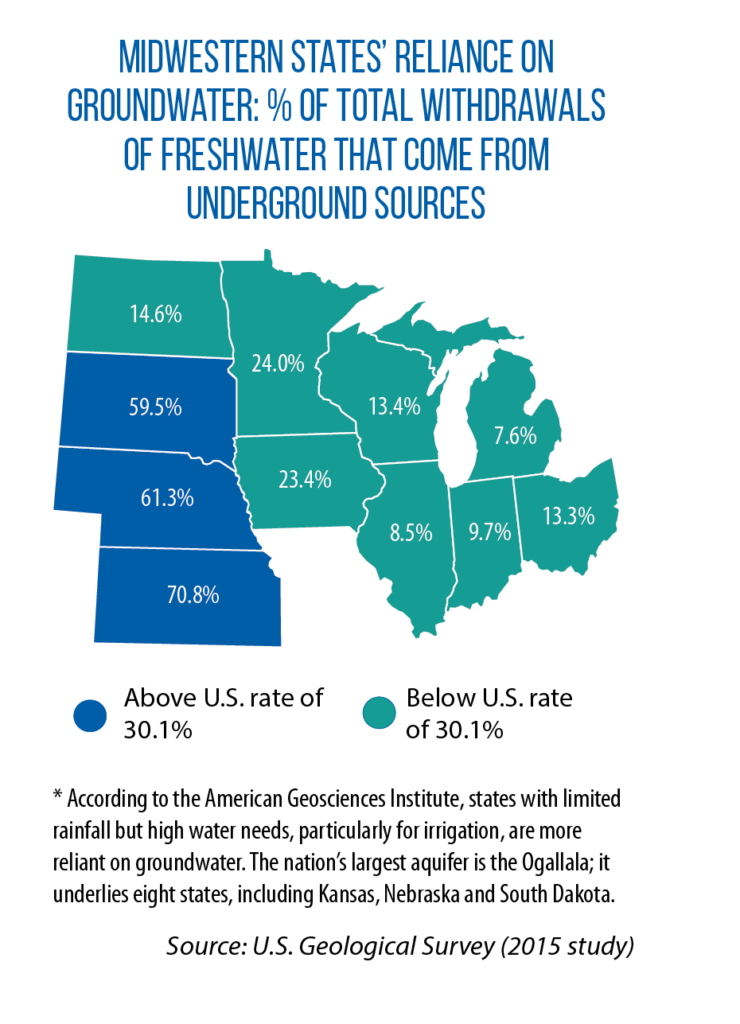

He said one county in his state is on pace to lose its groundwater in as little as seven years. In other areas, estimates show that a continued depletion of the Ogallala Aquifer means a total loss in 10, 14 or 50 years.

“All of this started with over-allocation [of water resources] back in the days when we didn’t know that this was a limited supply,” Highland said. “Nobody’s to blame. It happened.

“Now we’ve got to deal with it.”

‘Generational test of our democracy’

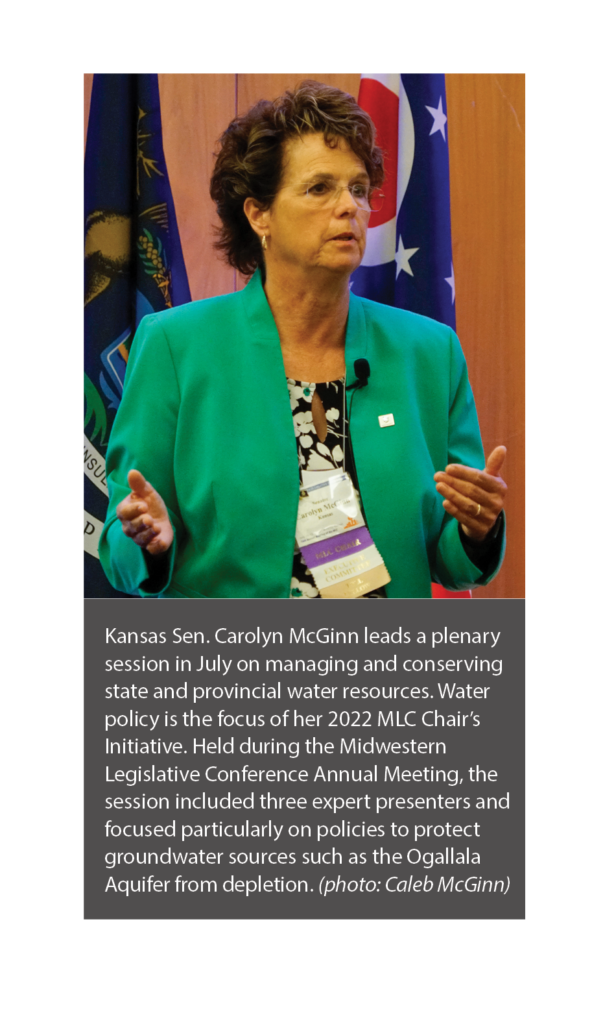

Addressing the problem of limited, and dwindling, groundwater resources was the focus of the July 2022 MLC session.

Kansas Sen. Carolyn McGinn, who chose water policy to be the subject of her 2022 MLC Chair’s Initiative, joined three panelists in leading the discussion.

“It offers a generational test of our democracy,” Lucas Bessire said about the challenge of water scarcity.

He grew up in southwest Kansas, on a farm where generations of his family were raised and relied on what seemed like an endless supply of water from underground.

“My great-grandfather was an early pioneer in deep-well irrigation,” Bessire said. “He believed the water would never run out, and he pumped it like there was no tomorrow.”

To this day, Bessire added, some common “myths” persist, standing in the way of the policy adjustments needed to “cut groundwater consumption to sustainable levels.”

Among those myths: Family farmers are responsible for the problem and don’t want to address it, and only continued depletion of the Ogallala Aquifer makes economic sense for these producers.

“Farmers know it’s a problem; they know what to do about it,” said Bessire, author of the book “Running Out: In Search of Water on the High Plains.” “They also realize individual action is insufficient to [address] the scale of depletion.

“In other words, depletion cannot be solved by policies that only incentivize voluntary, individual actions by producers.”

According to Bessire, the interests of far-away agribusiness owners and commodity-market investors have held too much sway — at the expense of local farmers, business owners and residents.

“For independent producers, growing irrigated corn in a dry range can sometimes feel like betting against a stacked deck,” he said. “Most of our losses are papered over by farm subsidies, crop insurance and bank loans. Such aid can compel farmers to double down on wasteful practices, but even most of these short-term gains don’t stay in our communities.”

A framework for reshaping state water policy

A restructuring of farm finance was one of several ideas offered by Bessire to end what he called a current “race to the bottom.” He also said states must have policies and water-permitting systems that reflect “the real value of groundwater,” and must ensure that any incentives for reducing water use be tied to “collective, fair and enforceable benchmarks.”

Another priority of Bessire’s: ensuring that local groundwater districts (such as those in place in Kansas) represent all interests in the community, not just a select few water users.

In Kansas, Rep. Highland led the work of a special legislative committee that took a deep-dive into the state’s water challenges and future. That led to this year’s introduction of HB 2686. It did not pass, but Highland expects many of the proposals to reappear in future sessions — creating a cabinet-level Department of Water and Environment, imposing new or increased fees on water users to raise revenue for water conservation and recovery, requiring groundwater districts to develop plans to reduce groundwater declines by 50 percent, and demanding more reporting by these districts as well as additional state oversight.

“Good bills take time [to pass],”Highland said. “We all know that, and I think we’ve laid the groundwork.”

According to Griggs, groundwater depletion should no longer be thought of as only a “western” or “Great Plains” problem.

It is spreading.

For example, the most recent interstate disputes have involved Georgia, Florida, Tennessee and Mississippi.

“If you’ve ever been to these regions, you know they’re not lacking for water, but what they’re lacking is regular precipitation,” Griggs said. “And one of the things that groundwater does is allow producers to irrigate when they need to.”

Within a state, he urged lawmakers to craft policies with the view of groundwater, just like surface water, as a public resource.

“Dairies move. Meat plants burn down and move. Farms move,” he said. “But cities can’t move. Neither can rural communities.”

Kansas Sen. Carolyn McGinn has chosen water policy as the focus of her Midwestern Legislative Conference Chair’s Initiative for 2022. A series of articles is appearing in Stateline Midwest this year in support of this initiative. A special session on this topic also was held during this year’s MLC Annual Meeting.