For states, the work on ‘forever chemicals’ has just begun, and potential economic effects on agriculture loom large

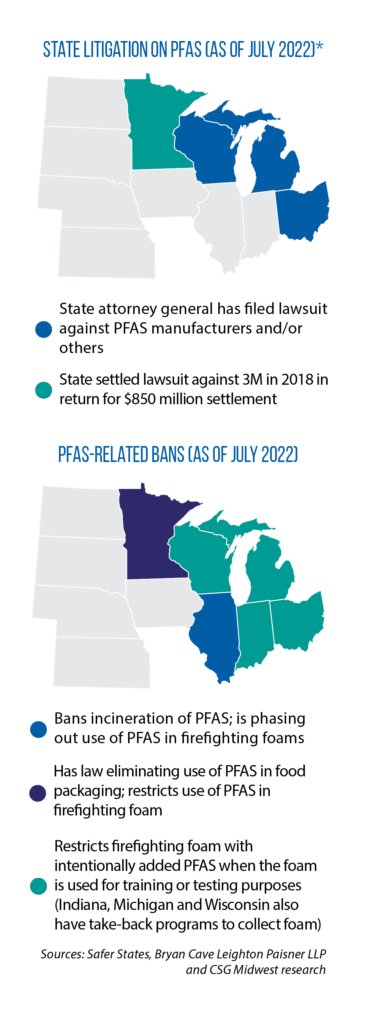

Over the past two years, policy “firsts” have cropped up in state legislatures across the country to deal with the problem of PFAS, a class of widely used chemicals linked to harmful health effects in humans and animals. In the Midwest, Illinois became the first U.S. state to ban the incineration of PFAS (HB 4818), and Minnesota is the first in the region to outlaw these chemicals in food packaging (SF 20).

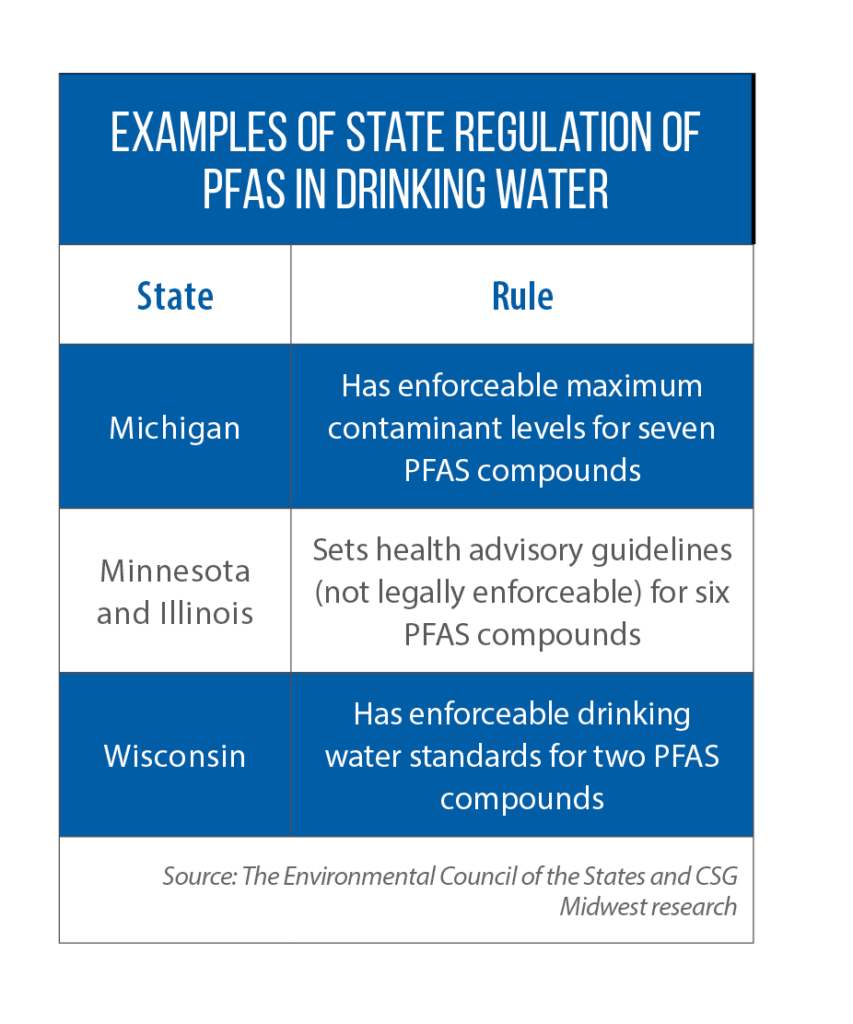

Wisconsin, for the first time, now has enforceable limits on levels of certain PFAS chemicals in community drinking water systems, joining Michigan in the Midwest.

Outside the region, some of the recent actions have been even further-reaching.

Maine, for instance, is prohibiting all non-essential uses of PFAS in products, and after sewage sludge was discovered to be a source of widespread PFAS contamination on farmland, the state banned the use of sludge as fertilizer. Also this year, Maine legislators established a $60 million trust fund for farmers whose land and products have been contaminated by PFAS. Through the fund, the state will purchase contaminated property, replace the lost income of farmers and monitor the health of affected families.

In Vermont, residents exposed to PFAS contamination now have a right to medical monitoring (paid for by PFAS polluters).

“It’s everywhere, and the cleanup is very difficult to do and very expensive,” Minnesota Rep. Ami Wazlawik says about the challenges posed by PFAS contamination. “So you have the prevalence of the chemicals in the environment, the fact that they are ‘forever chemicals’ that stick around, and then the negative health impacts.”

‘Turn off the tap’

All of those concerns led Wazlawik to become a leading voice on PFAS-related issues in the Minnesota Legislature. Her focus, in particular, has been on measures to “prevent further contamination.” That’s why she sponsored the food packaging bill from 2021, and introduced measures this year to ban the manufacture and sale of PFAS-containing cosmetics, cookware, ski wax and apparel (none of the legislation from 2022 passed).

Sarah Doll, national director of the group Safer States, refers to bills like these as a “turn off the tap” approach to PFAS. States have been at the forefront of these policies as well as two other types of strategies, she says. One, “figure out the problem,” through more testing and monitoring, as well as studying the health effects. Two, “address the problem” — investing in PFAS cleanup, establishing regulatory standards, suing polluters, etc.

The “turn off the tap” approach has particular appeal because of the “forever” nature of these chemicals, says A. Daniel Jones, a biochemistry professor at Michigan State University and associate director of the school’s Center for PFAS Research.

“If we keep manufacturing more of them, and they don’t go away, the levels are just going to increase unless we do something about it,” he says.

But instituting such bans can be difficult.

As a class of chemicals, Jones says, PFAS can have some “really important functions, so we’d like to be able to distinguish between what are the essential needs and then where there are some good substitutes that are available and that would not be just better for our health, but better for our economies and the ecology.”

PFAS refers to a class of many different chemical compounds. Two of them, PFOA and PFOS, have “become the poster children for PFAS,” Jones says, because the toxicity and health effects of these particular compounds are relatively known. The same cannot be said for many other chemical compounds in the PFAS family that remain in use today. (PFOA and PFOS are no longer manufactured in the United States.)

In Minnesota, Wazlawik says, one reason for the success of her food-packaging ban was that parts of the food industry already were moving toward PFAS alternatives in its products.

According to Doll, another policy lever for states is to help private industry find those alternatives. “It’s not just about dinging the companies,” she says.

Minnesota has a university-led Technical Assistance Program to help businesses with environmental stewardship. In the state of Washington, a recent law directs the Department of Health to designate chemicals of concern and then identify the products in which these chemicals are being used.

To ban the use of these chemicals, the department must first demonstrate that “safer alternatives are feasible and available.”

‘All over the planet’

The Environmental Working Group, a nonprofit, nonpartisan research and advocacy organization, tracks PFAS pollution in public and private water systems, and then regularly updates its national findings by state. As of June, it had documented close to 3,000 contaminated sites in the United States. Michigan has among the highest number of these sites, but Jones says that’s because the state has been a leader in terms of monitoring and testing.

“These chemicals are all over the world now, but Michigan has taken a much more aggressive role in trying to figure out where these chemicals are,” Jones says. “That’s been really important, because we need to understand what the scope of the problem is and how to prioritize cleanups. Where is it the worst? Where are the hotspots?”

Along with widespread testing for the presence of PFAS in the environment, Michigan has regulatory standards for levels of PFAS in drinking water, surface water, groundwater, and the releases by wastewater treatment plants. In recent years, too, legislators have invested heavily in PFAS contamination and cleanup — most recently with this year’s SB 565, which specifies that $55 million in state water revolving funds be used to eliminate PFAS and other emerging contaminants in drinking water.

According to Wazlawik, much of the work in Minnesota is being guided by a PFAS “blueprint,” an agency-led effort that prioritizes the state’s response. In future sessions, she says, much of the legislative role will be to adequately fund those priorities.

Part of the focus in Minnesota, and other states, is getting a better handle on the risks of different PFAS chemicals to human health. Jones says a colleague at MSU’s Center for Policy Research aptly refers to PFAS as “general messer-uppers.”

“They’re not your classical environmental poison,” he says. “They mess up a lot of biological functions, and then the question is, at what level does that become significant? And we just need to know more.”

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, high levels of certain PFAS may lead to increased cholesterol levels, a greater chance of kidney or testicular cancer, small decreases in infant birth weights, and an increased risk of high blood pressure.

PFAS fallout for farmers

To date, much of the attention on PFAS has related to the contamination of drinking water.

But Jones says the focus of states may turn more and more to the presence of PFAS on agricultural land, and in crops and livestock. To date, that problem has been most acute in the Northeast, as evidenced by Maine’s new $60 million trust fund for impacted farmers.

Earlier this year, though, the state of Michigan issued a consumption advisory regarding beef from a farm in the state. The cause: the use of biosolids containing PFAS on the land where the cattle were located.

“Some groups estimate that 20 percent of the farms may already have contaminated biosolids spread on them,” Jones says. “If that’s the case, what do we do next? How do we preserve our farms? Can you add things into the soil that keep the PFAS chemicals from getting into the crops?”

Those are among the many questions that may lie ahead for legislators, whose work on addressing the impacts of “forever chemicals” has just begun.

Kansas Sen. Carolyn McGinn has chosen water policy as the focus of her Midwestern Legislative Conference Chair’s Initiative for 2022.

Tackling the PFAS problem: Five examples of strategies from Midwest

ENACT LAWS BANNING PFAS IN CERTAIN PRODUCTS

ENACT LAWS BANNING PFAS IN CERTAIN PRODUCTS

Minnesota will soon become the first state in the Midwest to ban the use of PFAS in food packaging. Under SF 20, signed into law in 2021, “No person shall manufacture or knowingly sell … a food package that contains intentionally added PFAS.” The law takes effect in 2024. According to Safer States, which tracks PFAS-related legislation, 10 other U.S. states have taken steps to eliminate PFAS in food packaging. To date, the most common state action has been to ban or limit the use of firefighting foam with PFAS — including laws in Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio and Wisconsin.

TEST THE WATER AND RAISE PUBLIC AWARENESS

TEST THE WATER AND RAISE PUBLIC AWARENESS

Many Midwestern states have expanded PFAS testing and monitoring in drinking water. That includes Minnesota, which has an interactive online dashboard that allows residents to find out levels of PFAS (if any) in their community water systems. In unveiling this new resource, the Department of Health noted that Minnesota has joined states such as Illinois, Michigan and Ohio in conducting statewide testing of PFAS in drinking water.

SET LIMITS ON THE PRESENCE OF PFAS IN THE WATER AND AIR

SET LIMITS ON THE PRESENCE OF PFAS IN THE WATER AND AIR

Michigan and Wisconsin are among the states with enforceable standards that require action to be taken if certain PFAS compounds are detected in local drinking water systems at or above levels considered harmful to human health. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency is planning to adopt standards that are more stringent than any current state-level limits. Some states also have established regulatory standards for the presence of PFAS in surface water (Michigan, Minnesota and Wisconsin), groundwater (Michigan), soil (Michigan and Wisconsin), and the air (Michigan), according to The Environmental Council of the States.

INVEST IN PFAS REMEDIATION AND CLEANUP

INVEST IN PFAS REMEDIATION AND CLEANUP

Earlier this year, Michigan lawmakers made a historic $4.7 billion investment in the state’s water infrastructure. One area of emphasis: PFAS cleanup. Language in Michigan’s SB 565 allocates $55 million in state water revolving funds to address PFAS and other emerging contaminants in drinking water. Another $15 million will be used to clean up a single PFAS-contaminated site in the state.

FILE LAWSUITS AGAINST PFAS POLLUTERS

FILE LAWSUITS AGAINST PFAS POLLUTERS

Four years ago, Minnesota reached a $850 million settlement with 3M. The state had sued the company over the degradation of drinking water and other natural resources in parts of the Twin Cities metropolitan area due to the production of PFAS. Money from the lawsuit is going to 14 impacted communities to invest in their drinking water infrastructure. According to Safer States, Michigan, Ohio and Wisconsin are among the 13 U.S. states where attorneys general have active lawsuits over PFAS contamination against manufacturers and others.