How and why states are partnering with businesses on child care

Public-private initiatives will be part of broader North Dakota legislative proposal in 2023; other states in Midwest have started new grant programs and expanded tax credits

A decade ago, during the Bakken oil boom in western North Dakota, then-Mayor Brent Sanford had a workforce challenge on his hands: employers in his hometown of Watford City, with a population of just 1,744 people at the time, were struggling to attract workers because little or no child care services were available.

his hands: employers in his hometown of Watford City, with a population of just 1,744 people at the time, were struggling to attract workers because little or no child care services were available.

Led by Sanford, the city collaborated with the local school district, county officials, the state and the business community to find a unique solution.

City officials identified land for a new child care facility and apartment complex for teachers and first-responders, and a mix of public dollars and business donations allowed construction to commence.

Within five years’ time, a facility with the capacity to serve up to 211 children had opened. Watford City has since grown to about 6,000 residents, and another child care center, with some financial backing from the county, is slated to open in 2024.

Today, Sanford is still immersed in addressing child care shortages, but now for the entire state as North Dakota’s lieutenant governor and Gov. Doug Burgum’s point person on the issue.

Today, Sanford is still immersed in addressing child care shortages, but now for the entire state as North Dakota’s lieutenant governor and Gov. Doug Burgum’s point person on the issue.

“The desire is there [to address the problem],” Sanford says. “It’s not like we have to get attention for it. It’s a matter of figuring out what’s going to be the best return on our investment.”

‘A real workforce crunch’

That task is, in part, up to the Early Childhood Council. Established by the legislature in 2021 (HB 1416), the group includes a mix of lawmakers, child care providers, state agency heads and child care providers. Sanford serves as chair of the group.

In September, he and Burgum released a framework for 2023 legislative action to address the three obstacles that families typically face: affordability, accessibility and quality of services. While details are to be worked out, Sanford says, various elements of the plan would cost the state an estimated $70 million to $80 million over the next two years.

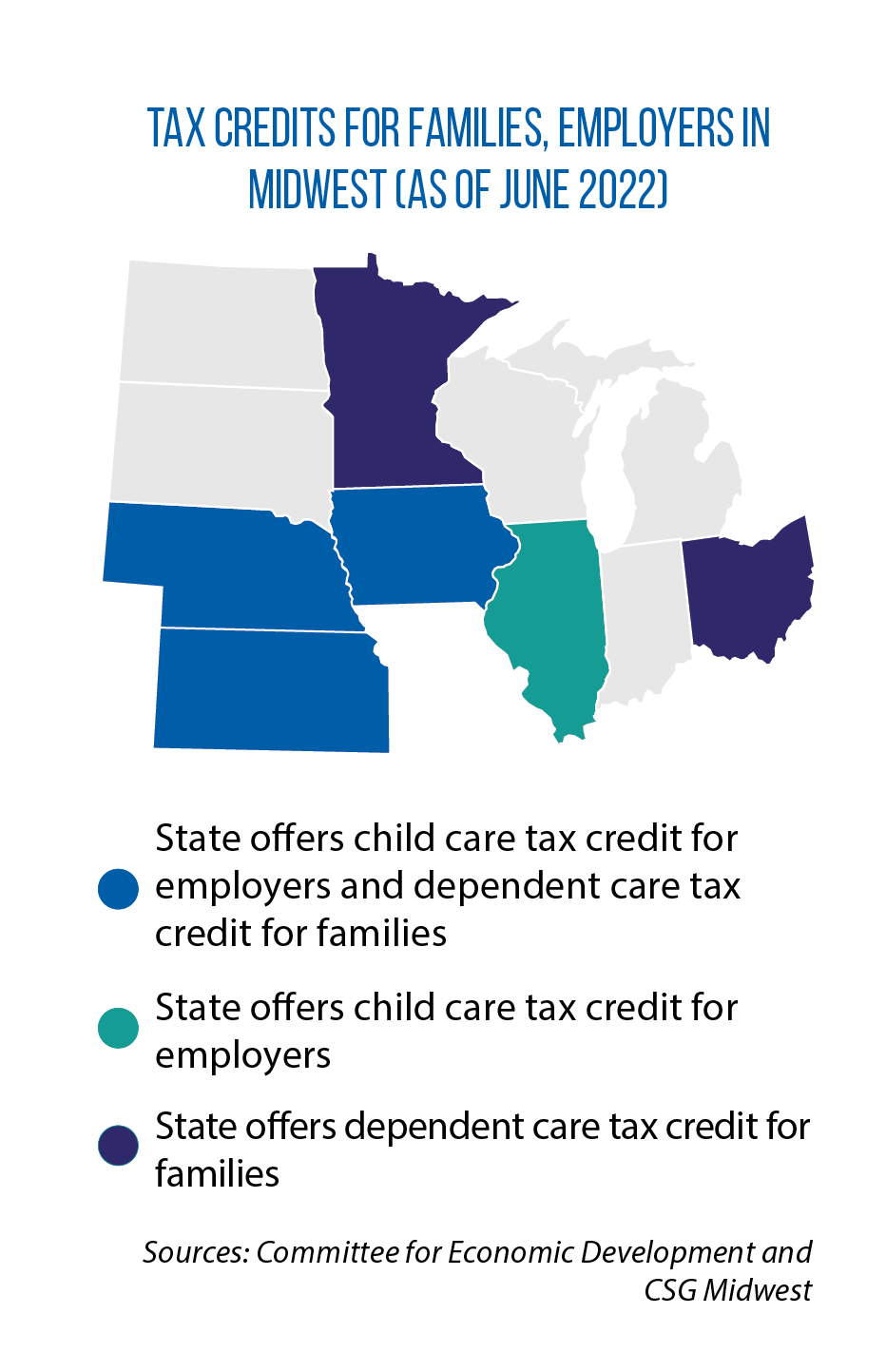

Ideas include expanding eligibility for families to get state assistance in paying for child care, establishing a state-level child care tax credit (similar to the existing federal credit) for low- and middle-income households, and increasing the rates paid by the state to qualifying child care providers.

Part of the plan also will focus on one of the lessons Sanford learned from his time as mayor and as council chair — the value of partnering with businesses to make work-based child care part of the solution to shortages.

“We’ve got a real workforce crunch with not having enough people for the jobs that are coming in,” Sanford says. “Having anything to offer in the way of child care is a good advantage, so for us to help narrow the gap is most effective.”

Part of North Dakota’s proposal envisions the state providing some kind of matching investment for employers who offer workers a child care benefit (a certain dollar amount to be spent on child care).

Additionally, Sanford says, new public-private partnerships with businesses need to be pursued, particularly to help parents and other wage-earners who work nontypical hours and need a nontraditional solution to their child care needs.

“There’s never enough day care,” Sanford says. “If employers are saying, ‘This is a problem for us,’ that makes a difference.”

North Dakota and many other states in the Midwest are looking for the broader business community to be part of the solution, with policy levers that include tax incentives and grants to build child care capacity.

‘Work that allows other work’

This year in Iowa, legislators established a nonrefundable state version of the federal Employer Provided Child Care Tax Credit.

The goal of the credit is to encourage businesses to establish and operate their own child care facilities, or to contract with existing providers to provide such services to workers.

Under HF 2564, which takes effect in 2023, businesses can get a credit of up to 25 percent for operating their own facility or up to 10 percent for contracting the services (same as the federal credit).

Iowa Rep. Jane Bloomingdale, who led legislative efforts on HF 2564, says mirroring the existing federal tax credit was a simple way to provide a state incentive because legislators didn’t have to re-invent the wheel.

“Right now, we have just a handful of businesses across the state that take advantage of the federal tax credit,” she adds. “I would love to see it make a difference quickly. I’m hoping that the state tax credit will get that to double in the first year and build from there.”

A total of $2 million will be made available to Iowa businesses.

Another strategy being used by Iowa: allocating state grants for individual businesses or employer consortia that commit to building onsite child care centers or providing the care via new partnerships with existing providers.

As of September, Iowa had awarded $75.6 million to 191 projects through the Child Care Business Incentive Grant. The result so far has been the addition of more than 10,700 new child care slots in Iowa.

In November 2021, Michigan launched what it has dubbed a “trishare” pilot program, with employers, qualifying workers and the state itself equally splitting the costs of building up child care capacity.

In different regions of the state, an organization has been tapped to serve as a “facilitator hub,” serving as an intermediary between employers, families and child care providers as well as providing overall management of the tri-share model.

In Kansas this year, lawmakers expanded the reach of a tax credit for employers: a credit equal to up to 50 percent of the costs of opening an onsite child care center, or 30 percent for providing a benefit for workers to access the care somewhere else in the community.

According to the group Kansas Action for Children, the credit previously had been available only to large corporations and financial institutions. This year’s HB 2237 opens up the tax incentive to small businesses as well. Up to $3 million in credits may be issued annually.

Illinois also offers businesses tax credits to offset the costs of starting up and operating a child care facility for workers, as well as a separate program for manufacturers that offer on-site services.

Wisconsin has been one of many states to direct additional federal funding from the American Rescue Plan Act to child care.

“[It’s] the work that allows all other work,” Wisconsin Department of Children and Families Secretary Emilie Amundson says.

A total of $10 million in ARPA dollars has gone to Partner Up!, a grant program for Wisconsin businesses that buy slots at existing child care providers on behalf of their workers.

A ‘funding’ cliff ahead for state child care systems

Increasing the number of available child care slots is a central goal of these new state investments and public-private partnerships.

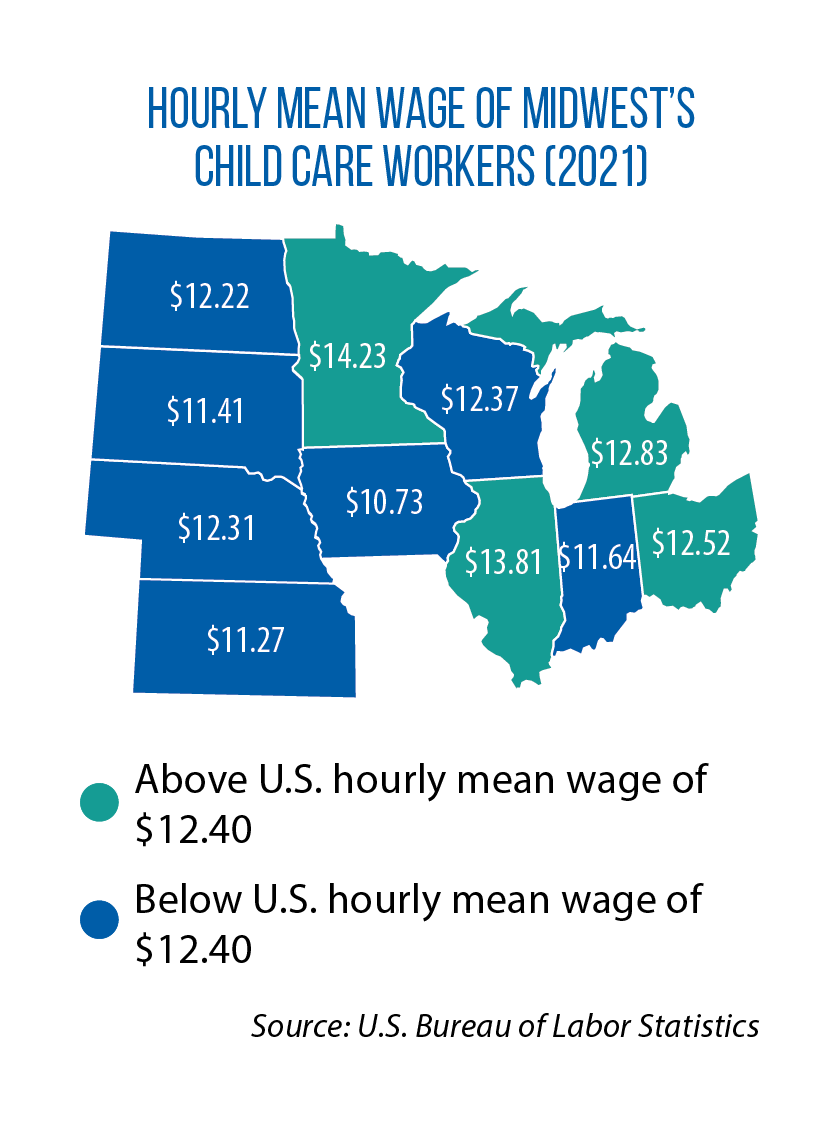

But states also need to be mindful of the need for more workers to provide the care for children, notes Cindy Lehnhoff, director of the National Child Care Association.

“Right now, we can’t find staff at the wages that providers can afford to pay,” she says. “If you don’t help providers directly, they can’t help their staff. The number one reason they can’t find staff, it’s a lot of hard work — physically and emotionally — for a little bit of money and no benefits or retirement.”

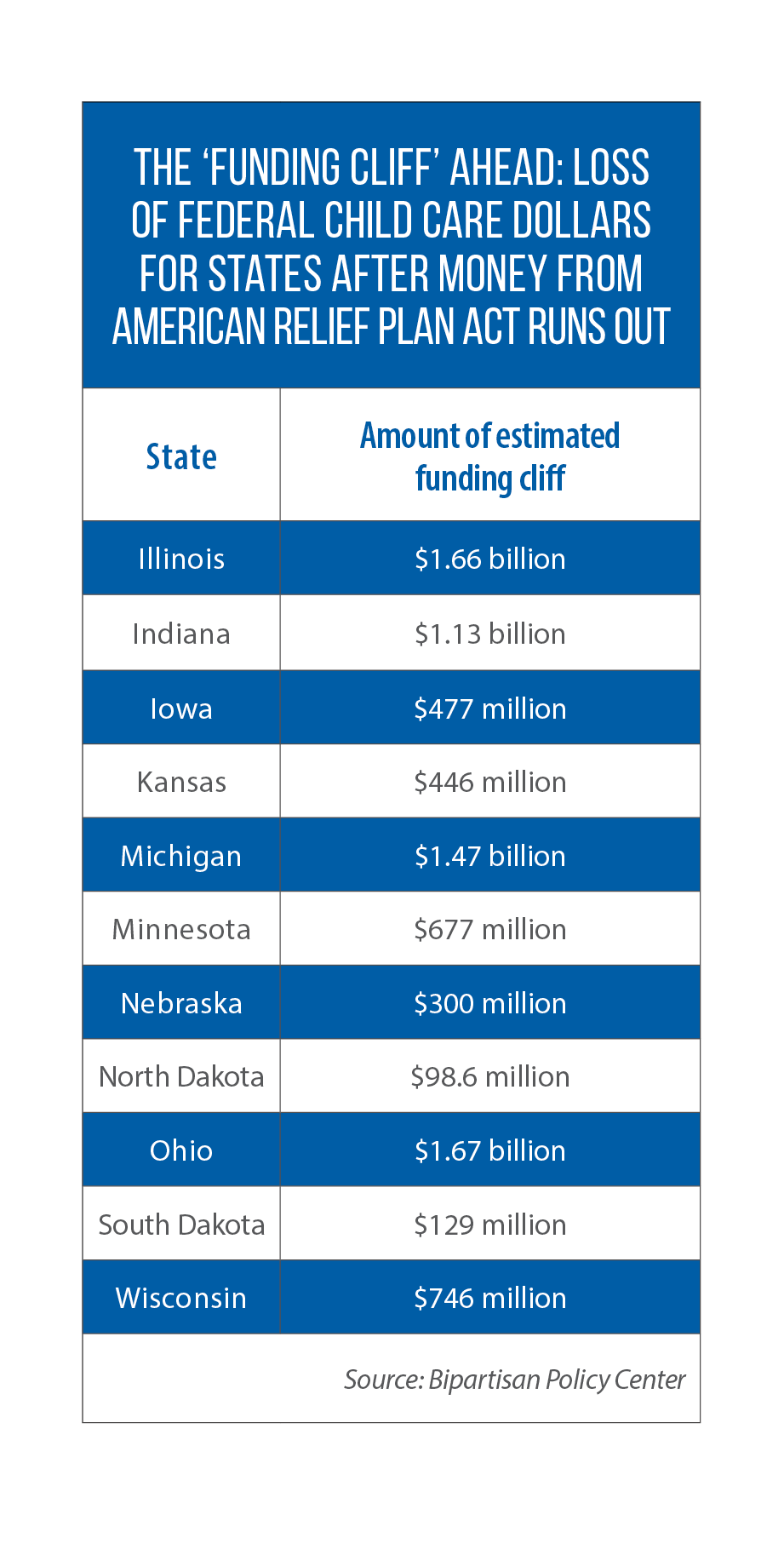

The American Rescue Plan Act helped as it was the first federal support for wages in states that chose to use their funds for child care workers, but that assistance is coming to an end, Lehnhoff notes.

The Bipartisan Policy Center estimates the end of pandemic-related federal support for child care will leave states facing a $48 billion funding “cliff,” which, in the Midwest, ranges from $98.5 million in South Dakota to more than $1.6 billion in Illinois and Ohio.

Without sustained federal funding, Lehnhoff predicts, “we’ll probably go backwards.”

Across the country, child care traditionally has been viewed as a service to be delivered by the private market and paid for by individual families — as opposed to publicly funded K-12 schools or universities. As a result, child care subsidies for providers and parents have been limited or nonexistent.

In North Dakota, state involvement in child care will expand if legislators approve the plan unveiled by Burgum, Sanford and others.

Along with the tax credits and business partnership, that plan is likely to include scholarships and on-the-job training for future and current child care workers, along with new grants and quality-based incentives for providers.

But Sanford says there is an important distinction between child care and education: the latter is a constitutionally mandated function of state government, the former is a private-sector endeavor. A teacher gets paid by the state and a local school district; a child care worker does not. That won’t change in North Dakota, Sanford says.