State of health coverage in the Midwest: Four takeaways from studies showing a drop in uninsured, but continued disparities and rising costs

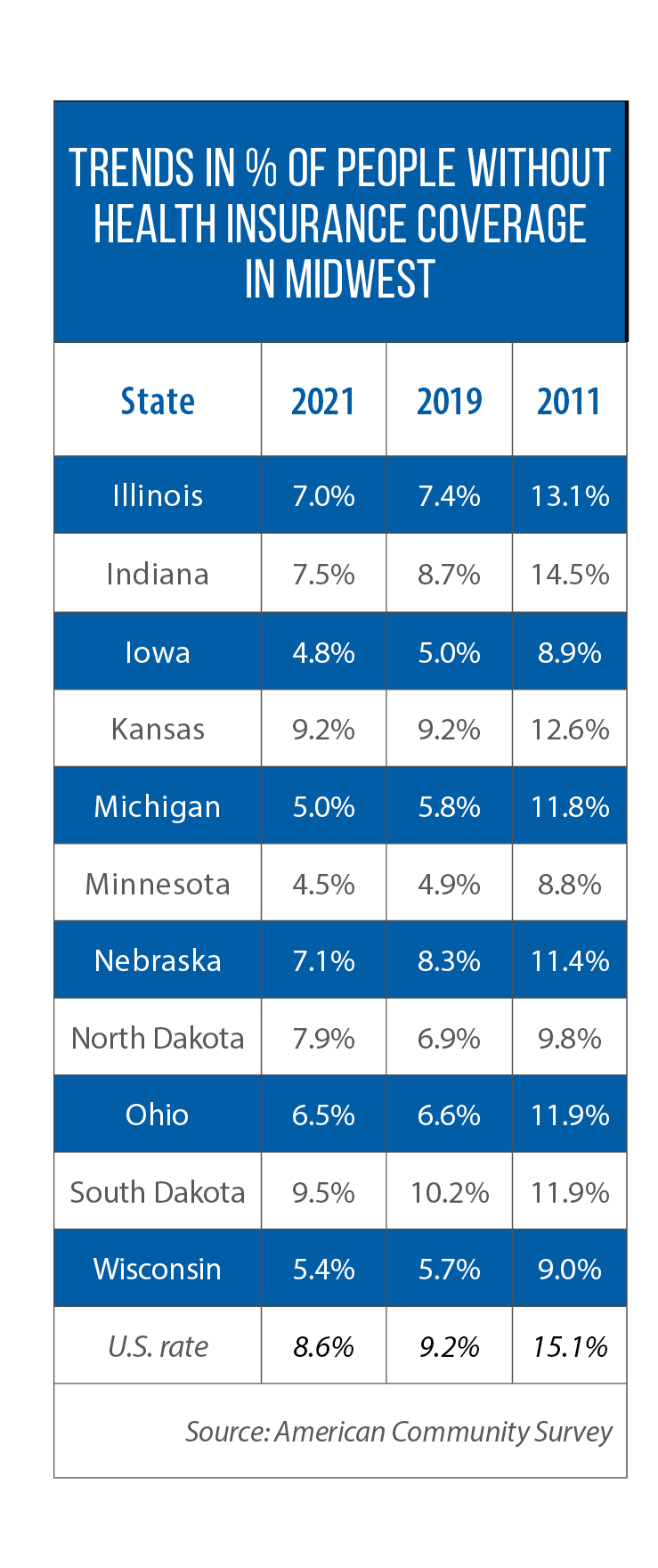

In 2022, several studies of trends in health insurance coverage found generally good news: since the Affordable Care Act became law in 2011, the percentage of Americans without health insurance coverage has dropped from 15.1 percent to 9.2 percent in 2019 – an improvement likewise seen in all Midwestern states.

Laws passed in response to the COVID-19 pandemic – the Families First Coronavirus Response Act of 2020 and the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 – helped drive the percentage of uninsured Americans even lower from 2019 to 2021 in most states.

But those same studies noted continuing disparities in who is covered and found that questions about affordability remain. Here are four trends of note in Midwestern states.

Coverage has improved since 2011, but unevenly

The percentage of uninsured people fell in all Midwestern states in the 10 years since the Affordable Care Act became law in 2011, and fell further from 2019 to 2021, except in Kansas and North Dakota, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

In North Dakota, the percentage actually rose from 6.9 percent in 2019 to 7.9 percent in 2021 while in Kansas, it stayed flat, at 9.2 percent.

In North Dakota, the percentage actually rose from 6.9 percent in 2019 to 7.9 percent in 2021 while in Kansas, it stayed flat, at 9.2 percent.

The Census Bureau attributes variations in states’ rates over the 10-year period to factors like differences

in age of the population, economic conditions, and policy changes like the ACA’s Medicaid expansion option for states.

All Midwestern states but Kansas, South Dakota and Wisconsin had adopted this expansion before 2022. From 2011 to 2021, Kansas’ uninsured rate fell from 12.6 percent to 9.2 percent, South Dakota’s from 11.9 percent to 9.5 percent, and Wisconsin’s from 9 percent to 5.4 percent.

But expansion states’ rates dropped by more: Indiana’s fell from 14.5 percent to 7.5 percent, Minnesota’s from 8.8 percent to 4.5 percent, Michigan’s from 11.8 percent to 5 percent, and Illinois’s from 13.1 percent to 7 percent.

Additionally, the Rural Policy Research Institute at the University of Iowa says two federal policy decisions stabilized uninsured rates during the pandemic:

• The Families First Coronavirus Response Act prevents states that accepted enhanced Medicaid funding for the public health emergency from reviewing Medicaid recipients’ status until after the emergency is officially rescinded.

• The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services opened health insurance marketplaces for most of 2021 instead of the usual annual Nov. 1 to Jan. 15 enrollment period.

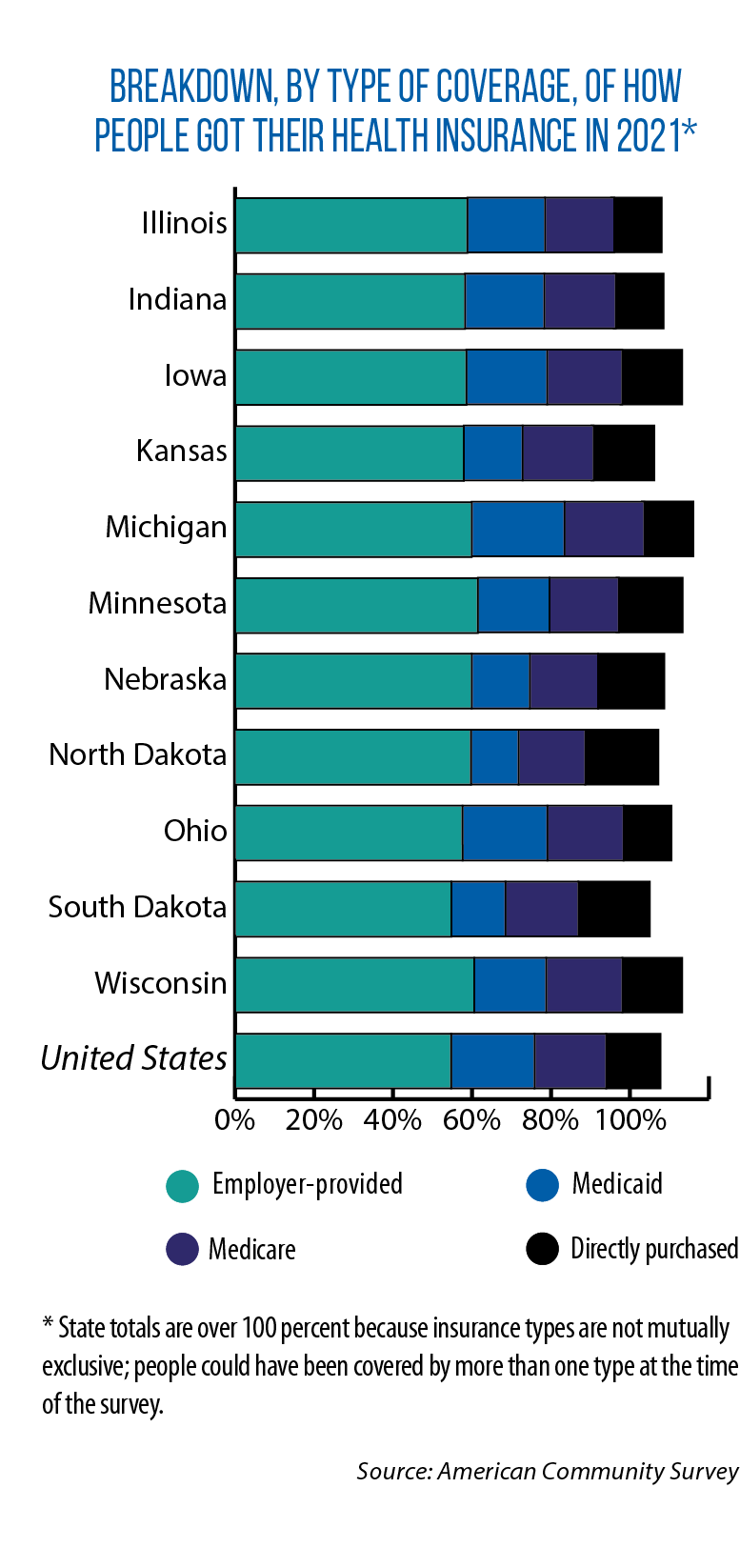

Private, employer-based insurance covers most people

Whether employer-provided or purchased from an insurance company or on a public exchange, private insurance covered the majority of Midwesterners in 2021. Employer-provided health insurance provides the bulk of this coverage, ranging from a low of 57.9 percent (Kansas) to a high of 61.5 percent (Minnesota).

Among public programs, Medicaid covers more people than Medicare in Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota and Ohio — all states that adopted Medicaid expansion.

Among public programs, Medicaid covers more people than Medicare in Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota and Ohio — all states that adopted Medicaid expansion.

Medicaid covers between a fifth and a quarter of people in Michigan (23.5 percent), Ohio (21.5 percent), Iowa (20.4 percent) and Indiana (20.1 percent). Medicaid coverage rates for other Midwestern states range from 12 percent in North Dakota to 19.7 percent in Illinois.

In South Dakota, where Medicare covers 18.4 percent of residents compared to 13.7 percent under Medicaid, voters in November approved an initiated constitutional amendment adopting Medicaid expansion. The state’s Department of Social Services estimates about 52,000 newly eligible residents will enroll once expansion has been implemented.

South Dakota is also one of the Midwestern states in which direct purchase of insurance from an insurance company or an exchange is most prevalent — that option covers 18.1 percent of residents, second only to North Dakota (18.5 percent).

Direct purchase rates in Nebraska (16.8 percent) and Minnesota (16.7 percent) are also higher than the other Midwestern states, where direct purchase ranges from 15.9 percent in Kansas to 12.1 percent in Ohio.

But overall coverage rates vary by age, race

Nationwide, uninsured rates vary widely by age — partly as a function of Medicare and programs targeting younger children — and race, according to an American Community Survey brief released in November.

Medicare covers those ages 65 and older, while children under age 19 may be included in their parents’ insurance coverage, Medicaid and/or the Children’s Health Insurance Program.

For example, no Midwestern state’s uninsured rate for adults ages 65 and older is even 1 percent.

At the other end of the age spectrum, for those under 19 years of age, uninsured rates in the Midwest range from 3 percent in Michigan and 3.2 percent in Illinois to 7.3 percent in North Dakota.

While those ages 19 to 26 are eligible to be covered by their parents’ policies, Midwestern states’ uninsured rates among adults ages 19 to 64 range from 7.1 percent in Michigan to 13.3 percent in South Dakota and 13.5 percent in Kansas.

The ACS brief also found a wide coverage gulf persisting between Whites and Asians on one end of the range and Hispanics and Native Americans at the other. Nationally, just 5.7 percent of Whites and 5.8 percent of Asians were uninsured in 2021 compared to 9.6 percent of Blacks, 17.7 percent of Hispanics and 18.8 percent of Native Americans.

Within the Midwest, the percentages for White uninsured range from 3.4 percent in Minnesota to 6.9 percent in Kansas; for Black uninsured, from 7.4 percent in Wisconsin to 20.3 percent in North Dakota; for Asian uninsured, from 4.2 percent in Michigan to 9.6 percent in Ohio.

The percentages for Hispanic uninsured range from 10.1 percent in Michigan to 20.1 percent in Nebraska and 20.3 percent in Kansas; and for Native Americans, from 12.5 percent in Michigan to 35 percent in South Dakota.

“Racial differences in health insurance coverage persisted across age and selected characteristics and reflect disparities in social determinants of health, such as income and poverty status as well as employment,” the brief says.

Rising costs of insurance still a major obstacle

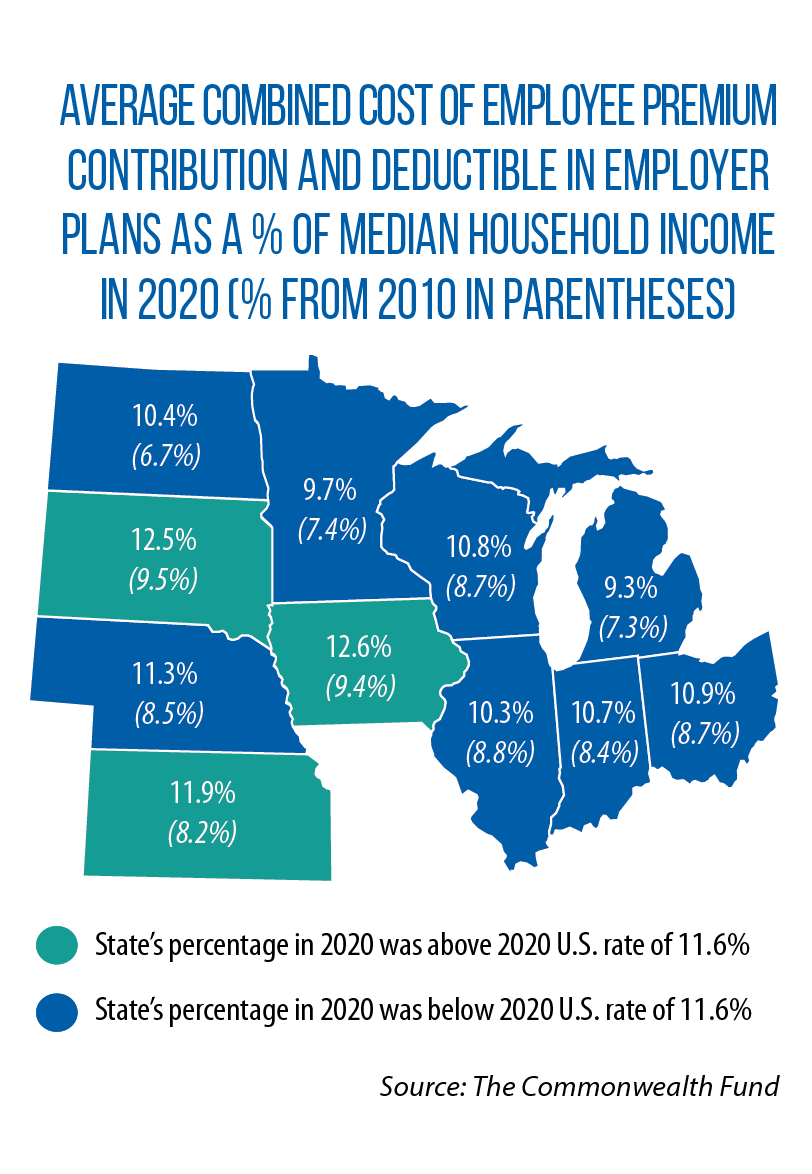

Coverage alone doesn’t help if the insured person can’t afford treatment. Reports issued earlier this year by The Commonwealth Fund suggest health insurance costs are taking larger bites out of middle-income families’ budgets and leaving them “underinsured.”

A September study found more than two in five working adults ages 19 to 64 were underinsured, defined as someone to whom at least one situation applies:

A September study found more than two in five working adults ages 19 to 64 were underinsured, defined as someone to whom at least one situation applies:

• Out-of-pocket costs over the prior 12 months, excluding premiums, were equal to 10 percent or more of household income.

• Out-of-pocket costs over the prior 12 months, excluding premiums, were equal to 5 percent or more of household income for individuals living under 200 percent of the federal poverty level ($27,180 for an individual or $55,500 for a family of four in 2022).

• The deductible constituted 5 percent or more of household income.

A January study of state trends in employer premiums and deductibles from 2010 to 2020 found that in 2010, worker contributions to insurance premiums and deductibles made up 10 percent of median income in no Midwestern state. By 2020, they did in all but Michigan and Minnesota.

“The high cost-sharing people face in many employer, individual-market, and marketplace plans is primarily driven by the prices that providers, especially hospitals, charge to commercial insurers and employers,” the latter report says. “These prices are the highest in the world. And consumers bear the burdens.”