Minus federal action, states ramp up activity on consumer data privacy

New laws are taking effect this year in a handful of states outside the region; enacted and introduced measures lay out mix of new consumer rights and business obligations

One reality about serving in the nation’s laboratories of democracy: On some issues, the lab can get shut down at any time, if a federal measure passes and includes preemption language.

Consumer data privacy appears to be one of those issues.

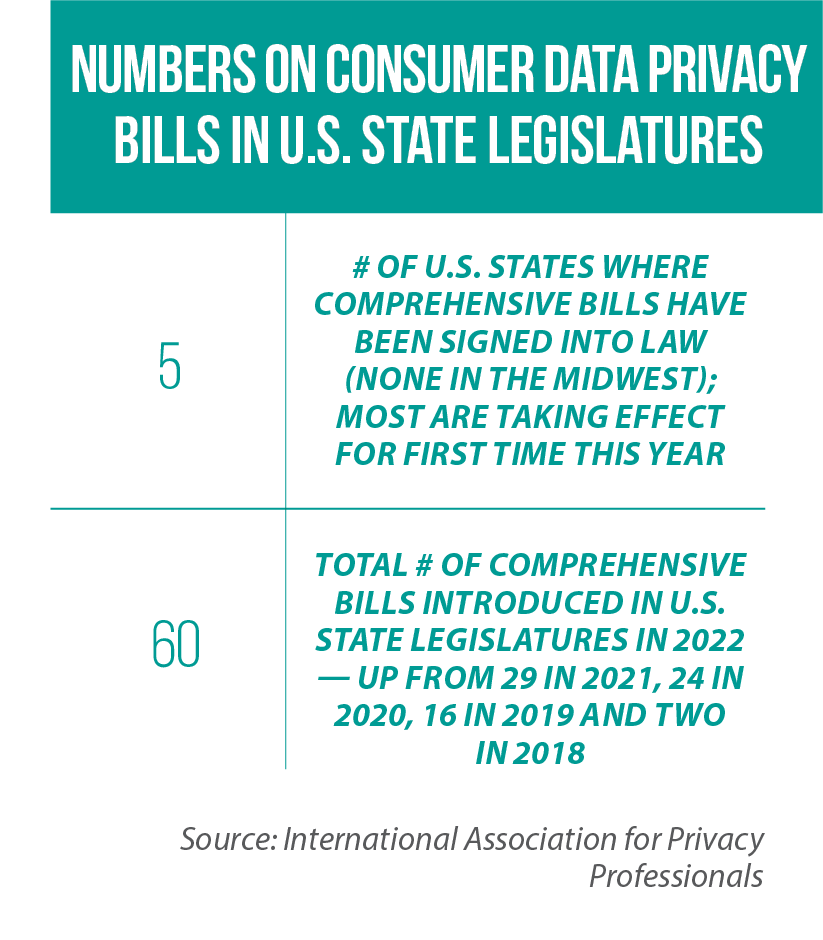

Minus action by the U.S. Congress, state legislators across the country have been crafting bills to establish new privacy protections for their constituents amid growing concerns about how companies collect, use and sell consumer data. As of early 2023, five states (none in the Midwest) had consumer data privacy laws in place, often mirroring each other in many ways in order to avoid a “patchwork” of laws and definitions.

At the same time, these enacted measures have enough substantive differences to get the label of “business friendly” or “consumer friendly.”

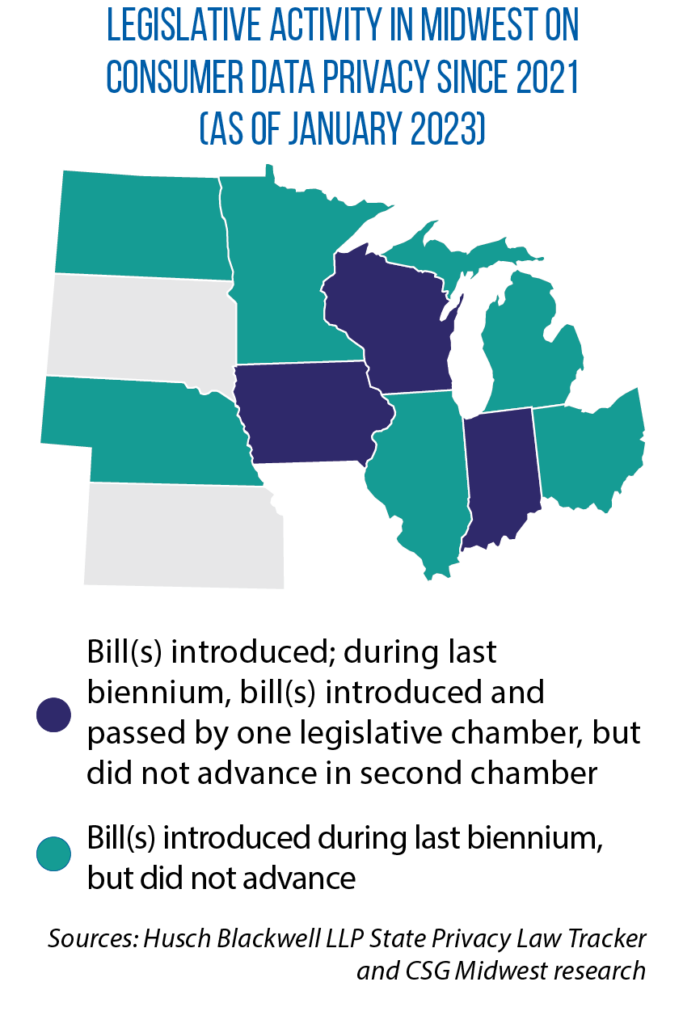

Since 2021, legislation has been introduced in most Midwestern states, and last year, measures were approved in three legislative chambers (see map). Many proposals will be under consideration this year as well, all while lawmakers watch for a breakthrough in the nation’s capital, where congressional leaders came closer than ever in 2022 to agreeing on a comprehensive federal law.

“I expect that whatever I get passed here in Minnesota is eventually going to be preempted by federal legislation,” says Rep. Steve Elkins, whose long professional background in data management and information technology made him a natural fit to be a point person on the issue. “But I also expect the legislation that we’re passing in the states is going to have a heavy influence on what Congress eventually does.

“That’s what I view as the long-term legacy of the work that we’re doing now — identify the issues, flesh them out, and then write good legislation that Congress can use as a model.”

David Stauss, a leading national expert on states’ work on consumer data privacy, agrees that all of this work of states is shaping the direction of federal policy. He points to laws taking effect this year in the “3 C” states (California, Colorado and Connecticut) as examples.

“Everybody realizes that a 50-state approach to privacy law would be a mess,” says Stauss, a partner at Husch Blackwell LLP and co-leader of the firm’s privacy and data security practice group. “What I think the advantage of the state approach right now is it allows things to be tried, rules to be proposed and changed. Also, it ingrains certain concepts and sets floors [on privacy rights] for what will happen at the federal level.”

One state may lead to another

In the meantime, Elkins believes this year’s implementation of new privacy laws in a handful of states will give momentum to legislative proposals in other states, including his own.

He recounts a recent experience of logging into the site of a national hotel chain.

“I went to update my [membership] profile, and there was an option that says, If you’re a resident of California or a couple of other states, you have these additional rights. Click here,” Elkins says. Increasingly, he believes Minnesotans will be asking: Why don’t I have these same rights?

“I went to update my [membership] profile, and there was an option that says, If you’re a resident of California or a couple of other states, you have these additional rights. Click here,” Elkins says. Increasingly, he believes Minnesotans will be asking: Why don’t I have these same rights?

In his work on consumer data privacy, Elkins has used as a starting point the Washington Privacy Act. (As of early 2023, the state of Washington had not passed the measure, but other state laws, with the exception of California’s, were modeled after it.) Elkins expects his legislation this year to again rely on the Washington framework, while incorporating recent enhancements in other states as well as some of his own ideas in areas such as how “precise geolocation” is defined in statute.

What are Elkins’ “must haves” for laws on consumer data privacy?

“They need to have things like the right to have an opt-out of having your data sold,” he says. “The right to know what data a company has about you. The right to correct inaccuracies in that data. The right to question decisions that have been made about you based on that data.”

‘What are the rules?’

Like Elkins, Wisconsin Rep. Shannon Zimmerman came to the legislature as a “data guy.” He and his wife started and successfully built up a language-translation company. More generally, too, Zimmerman embraces the value of “big data,” as a means of improving the experience of consumers and the lives of people.

“As a guy who loves tech, I think we’re living in the best times, this convergence of big data, AI and quantum computing,” he says. “We’re going to see cures to cancer, I hope, in my lifetime as a result of all this. “But I think one of the things that has been overlooked is, what are the rules? What are the ethical considerations as it relates to personally identifiable information?”

That’s where he believes state government, especially minus action at the federal government, must step in, and Zimmerman lays out three pillars for how his state should set new rules in the area of consumer data privacy.

That’s where he believes state government, especially minus action at the federal government, must step in, and Zimmerman lays out three pillars for how his state should set new rules in the area of consumer data privacy.

“Number one, I want a Wisconsin resident to be able to say to a data collector, what do you have on me? What have you collected? Number two, to whom have you shared or sold my private and personal information? And then, third, I, the consumer, should be able to say, ‘No, stop, delete it.’ ”

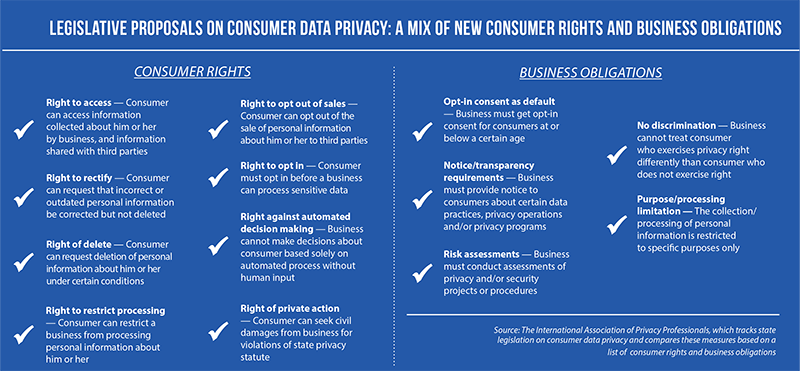

The International Association of Privacy Professionals tracks legislative activity in states, comparing the measures based on their inclusion or exclusion of eight specific “consumer rights” and five “obligations” put on business. The former category includes a consumer’s right to opt out of sales, a right not to have his or her sensitive data processed without first opting in, and a right not to have automated decisions made about him or her without human input.

Among the obligations on business: no discrimination against individuals who exercise their privacy rights and disclosure to consumers of data practices (see full list below).

New obligations on business

From the perspective of Caitriona Fitzgerald, for a law to be truly “consumer friendly,” it must uproot a model that she believes puts an unrealistic burden on consumers to secure privacy rights from each and every business with which they interact online.

“Instead, put an obligation on the companies that they can only collect what is reasonably necessary for what service they’re providing, and a few other limited services such as fraud prevention,” says Fitzgerald, deputy director of the Electronic Privacy Information Center. According to Fitzgerald, the five U.S. states with laws on the books have not met this “reasonably necessary” test; in contrast, the 2022 federal legislation did.

Minus this kind of blanket limit on data collection, Stauss says, some states have included statutory language that allows for a “universal opt-out mechanism.”

Minus this kind of blanket limit on data collection, Stauss says, some states have included statutory language that allows for a “universal opt-out mechanism.”

“There are emerging technologies, through browsers or browser conventions, that can send a signal to a website, ‘I want to opt out,’ “ he explains.

For consumers, this means not having to opt out every time, on every different company website.

Stauss notes, too, that some of the new state laws require businesses to obtain consent before collecting certain sensitive data. In its definition of “sensitive data,” for instance, Connecticut includes race and ethnicity, religious beliefs, health conditions, sexual orientation, biometric and genetic information, a child’s personal information, and the precise geolocation of an individual.

Another consideration for legislators: whether or not to require businesses to conduct data protection assessments.

“In a nutshell, the concept behind these provisions is that a business can be engaging in certain high-risk processing activities,” Stauss says. “So the states are saying you should conduct an analysis of your processing activity. You should consider factors to make sure that you’re only collecting the information that you need to collect. You’re getting rid of information after a certain time period. Those types of things.”

Private right of action?

Stauss adds that no states have yet to “ring the bell” on giving consumers a right to private action. Consumer advocates want individuals to be able to bring lawsuits for privacy violations, as opposed to relying on actions being initiated by state law enforcement.

Zimmerman balks at the idea of including such a private right of action in Wisconsin. “We already have a hyper-litigious society,” he says.

His measure from 2022 (AB 957) included a “30 day right to cure,” in which Wisconsin companies that violate the state law are given the opportunity to fix the violation. “If there is a second time, then the attorney general can say, ‘We’re going to now invoke action,’ ” he says.

The federal legislation from 2022 included a private right of action, Fitzgerald says, along with enforcement by federal and state authorities.

“There’s an Illinois biometric privacy law that has a private right of action,” she notes, “and that’s just proven to be a really, really valuable tool.”

The Illinois law dates back to 2008 and, among other provisions, requires entities to obtain written consent from an individual before collecting his or her biometric data. Individuals harmed by the violations have the right to pursue legal action. Last year, in a class-action lawsuit involving more than 45,000 truck drivers, an Illinois jury brought a $228 million judgment against BNSF Railway for violation of the biometrics statute, according to the Chicago Tribune. The suit centered on the railway’s collection of fingerprint data from the truck drivers.