Public funds for private-school enrollment? The question is getting a lot of attention this year in state capitols, and Iowa has a far-reaching new law

After years of failed attempts, Iowa lawmakers this session were successful in passing one of the most expansive education savings account (ESA) programs in the nation.

In contrast to previous session proposals — which based eligibility on family income levels, special-needs status, and attendance at a public school in need of “comprehensive support” — Iowa’s HF 68 provides universal eligibility.

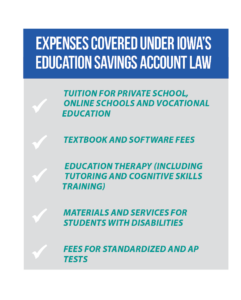

Once the law is fully phased in, any Iowa family will have access to an ESA to pay for private-school tuition costs, as well as other education-related expenses (see graphic).

Once the law is fully phased in, any Iowa family will have access to an ESA to pay for private-school tuition costs, as well as other education-related expenses (see graphic).

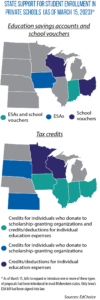

According to the school choice advocacy group EdChoice, of the 10 other states that provide ESAs (including Indiana, which supports qualified students with special needs), Arizona, Arkansas, Florida, Utah and West Virginia are the only other states that currently or will soon provide for universal eligibility.

Additionally, the value of Iowa’s new ESAs will be equal to the per-pupil rate used for public schools — a higher amount compared to measures from previous sessions.

What made the difference this year?

Iowa House Speaker Pro Tem John Wills, who served as the floor manager of HF 68, points to events from the year prior. In 2022, Gov. Kim Reynolds extended legislative session by a month to try and get an ESA bill to her desk. When that didn’t happen, she publicly endorsed primary opponents of members of her own party who didn’t support the proposal.

Iowa House Speaker Pro Tem John Wills, who served as the floor manager of HF 68, points to events from the year prior. In 2022, Gov. Kim Reynolds extended legislative session by a month to try and get an ESA bill to her desk. When that didn’t happen, she publicly endorsed primary opponents of members of her own party who didn’t support the proposal.

“Out of eight people who weren’t school-choice folks,” Wills explains, “seven of them lost their election.”

With the support of newly elected proponents, as well as the creation of a five-member House Education Reform Committee (which included Wills as a member and Speaker Pat Grassley as chair), the 2023 proposal was introduced and signed into law within the session’s first two weeks.

Consequences of choice?

Legislative momentum for these types of measures has accelerated in recent years, partially due to the impacts of pandemic-related school closures along with a national spotlight on K-12 instruction.

Legislative momentum for these types of measures has accelerated in recent years, partially due to the impacts of pandemic-related school closures along with a national spotlight on K-12 instruction.

“Parents [saw] what was going on, and they weren’t always happy with what they were seeing,” Wills says.

Both he and Reynolds also have emphasized the value of students’ enrollment in school being based not on ZIP code, but on a choice made by their family.

“Public schools are the foundation of our education system, and for most families they will continue to be the option of choice,” Reynolds said in signing HF 68.

“But they aren’t the only choice.”

Questions about the impact on public schools have been central to Iowa’s multi-year debate over ESAs. One particular concern has been the potential implications in rural areas if students leave for private institutions.

“I don’t expect that, all of a sudden, we’re going to hear this massive sucking sound out the front door of our rural schools,” Wills says.

As of the 2022-’23 school year, certified nonpublic schools were operating in 57 of Iowa’s 99 counties.

Under HF 68, public schools will receive categorical funding to offset student transfers to private institutions (around $1,200 per pupil).

Still, according to an analysis by the Iowa Legislative Services Agency, there will be an estimated net decrease of around $46 million for public schools by the fourth year of the law’s implementation (a 1.2 percent decrease compared to estimates without the ESA law in place). That analysis relies in part on an estimate of how many students will use ESAs and transfer.

Discrimination concerns

Opponents of such measures have also questioned whether state dollars should go to nonpublic and parochial schools that can legally deny a student admission due to a disability status or an LGBTQ+ identification.

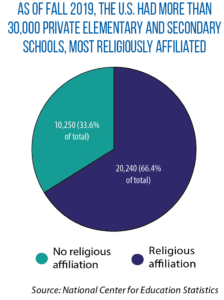

On multiple occasions, the U.S. Supreme Court has ruled in cases such as Carson v. Makin (2022) and Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue (2020) that statewide student-aid opportunities that are available to public and private schools cannot exclude religious institutions.

In addition, the “free exercise of religion” clause of the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution means parochial schools cannot be compelled by government to violate their religious doctrine — a doctrine which may be interpreted as not accepting students who identify as LGBTQ+.

In addition, the “free exercise of religion” clause of the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution means parochial schools cannot be compelled by government to violate their religious doctrine — a doctrine which may be interpreted as not accepting students who identify as LGBTQ+.

In Iowa, of the 183 certified nonpublic schools currently operating, 95 percent are religiously affiliated. In other words, the closest private school option for a gay or transgender student who wants to leave their public school could be an institution that does not allow them.

Wills says if there was a large enough group of these students, they would have the ability to start their own school, while acknowledging that, “it is a very expensive prospect to start a school and it is very tough to become accredited.”

Other proponents raised concerns that students with disabilities could also be denied admission. Federal code does not require private schools — even those that receive federal aid like the National School Lunch Program — to accept students with a disability or special needs if the resources needed to adequately care for such students are not offered at the school and go beyond minor adjustments. The NSLP also allows for religious exemptions to federal nondiscrimination laws that sometimes include sexual orientation and gender identity.

Wills says he has spoken with several private school superintendents throughout Iowa and, anecdotally speaking, found many do accept students with disabilities or IEPs.

Regardless, some states have taken efforts to enshrine in state statute anti-discrimination language applicable to private schools.

Nebraska Sen. Megan Hunt’s response this year was to introduce LB 487. It would bar public funds from going to schools that discriminate based on a young person’s sexual orientation, gender identity, or disability or special education status.

Nebraska Sen. Megan Hunt’s response this year was to introduce LB 487. It would bar public funds from going to schools that discriminate based on a young person’s sexual orientation, gender identity, or disability or special education status.

“We cannot allow this trend of just gesturing to the idea of religious freedom to grant automatic exemption from law,” Hunt says.

Entering this year, Nebraska did not have any school-choice programs in statute, according to EdChoice.

However, this year’s LB 753 (a bill advancing toward passage as of mid-March) would create a new tax-credit scholarship program. Individuals who donate to nonprofit, scholarship-granting organizations would get a tax credit from the state. These organizations, in turn, provide scholarships for students to attend private school.

During a February committee hearing, Gov. Jim Pillen testified in favor of the program by saying, “We cannot let financial burden of a family be an obstacle for these kids to get the best education that meets their needs.”

Tax-credit scholarship programs differ from ESAs in that the funds do not come directly from state coffers.

Still, Hunt questions the constitutionality in her state.

She says a mix of constitutional language, existing statutory definitions and state legal precedent over the meaning of terms such as “tax expenditure” and “to appropriate” support her claim that such scholarships should be considered “public funds” — funds that cannot go to private schools in Nebraska.

According to an analysis by University of Nebraska-Lincoln College of Law Associate Dean Anthony Schutz, “If one were to say that all tax expenditures are appropriations, it might cast too wide of a net, exposing all manner of tax expenditures to the substantive and procedural limits on appropriation. … None of the Court’s cases involve the question of whether forgone revenue through a tax-credit mechanism involves ‘public funds.’”

Schutz suggests LB 753 supporters may want to consider a ballot referendum asking voters to amend the constitution to more clearly allow for state dollars to go to private institutions — similar to previous attempts in the 1970s.

In Michigan this year, legislators passed a bill expanding the state’s existing civil rights laws to provide protection from discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity or expression.

As part of SB 4, signed by the governor in March, all educational institutions are prevented from denying services or admission based on these protected classes.

As part of SB 4, signed by the governor in March, all educational institutions are prevented from denying services or admission based on these protected classes.

“Religion is already protected from discrimination … but adherents of a religion are required to follow neutral, generally applicable laws,” Michigan Senate President Pro Tem Jeremy Moss, the sponsor of SB 4, says. “If a good or service is available on an open market, there should be no allowance to discriminate.”

Indiana’s enrollment trends

Indiana has strongly embraced school choice for many years. Still, the presence of financial-aid opportunities in this state has not necessarily resulted in big boosts in private school enrollment.

According to a 2021 Ball State University report, between 2007 and 2020, private school attendance in Indiana dropped from 69,708 (6.3 percent of total state K-12 enrollment) to 55,348 (5.1 percent of the total).

Although the introduction of a voucher program in 2011 led to an initial increase in private enrollment, peaking at 80,523 (7.3 percent) in 2015, there has been a continual decline in each ensuing year.

One explanation for the drop could be that Indiana, like every Midwestern state except Illinois, allows for inter-district transfers to other public schools.

“The ability to send your child to another local public school proved so popular in Indiana that it led to the real financial stress, if not death, of a lot of local private schools,” explains Ball State economics professor Michael Hicks, a co-author of the study.

He adds that the absence of local property tax revenue and busing services for private schools also has contributed to lower enrollment numbers.