The fentanyl threat and legislative response in the Midwest

Recently enacted laws include three approaches to harm reduction, as well as increased criminal penalties

“Reducing Harm, Increasing Criminal Penalties” ~ PDF

Introduction: ‘Single deadliest drug threat our nation has ever encountered’

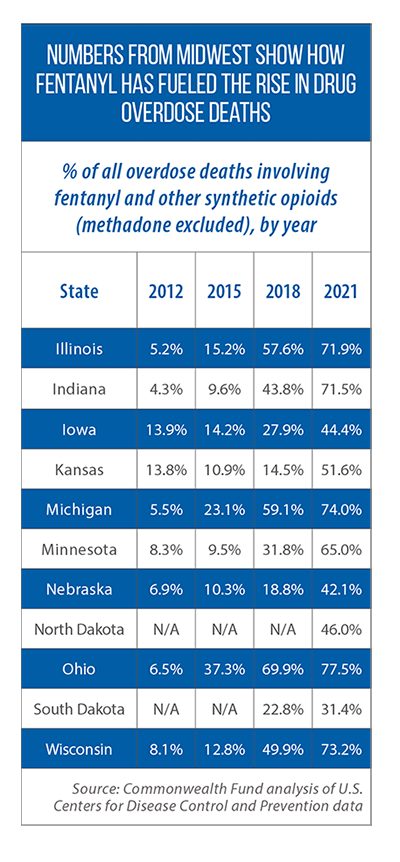

In less than a decade’s time, the number of drug overdose deaths in the United States more than doubled, reaching nearly 107,000 by 2021.

One of the striking aspects of this rise has been the increasing role played by fentanyl and other synthetic opioids. They were involved in close to 70 percent of all overdose deaths in 2021, compared to only 6 percent of the fatalities nine years earlier, according to a Commonwealth Fund analysis of federal mortality data. Anne Milgram, head of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, has said that fentanyl “is the single deadliest drug threat our nation has ever encountered.”

This threat has received considerable attention in the Midwest’s state legislatures, with many of the recent legislative proposals taking one of two approaches — and sometimes incorporating a mix of both.

The first approach is “harm reduction”: change a state’s laws or invest in new programs that prevent overdoses by reaching and helping people who use drugs. A second common approach has been to increase criminal penalties related to fentanyl trafficking and/or overdose-related deaths.

This Issue Brief was written by Tim Anderson of the Midwestern Office of The Council of State Governments. It was produced as part of CSG Midwest’s support of two binational, interstate committees of the Midwestern Legislative Conference: the MLC Criminal Justice & Public Safety Committee and the MLC Health & Human Services Committee.

Harm reduction strategies: A look at 3 common approaches in the Midwest

In this Issue Brief, we look at recent activity in the Midwest in three harm reduction areas:

1) policies on fentanyl test strips;

2) efforts to expand access to naloxone or other medications that can reverse an overdose from opioids; and

3) good Samaritan laws that provide legal immunity to individuals who reach out for medical assistance while either experiencing or witnessing a drug overdose.

We also explore how legal settlements with opioid manufacturers, distributors and retailers can help states fund harm reduction strategies, and summarize recent activity across the border in the province of Saskatchewan.

Approach #1: Fentanyl test strips as a harm reduction strategy

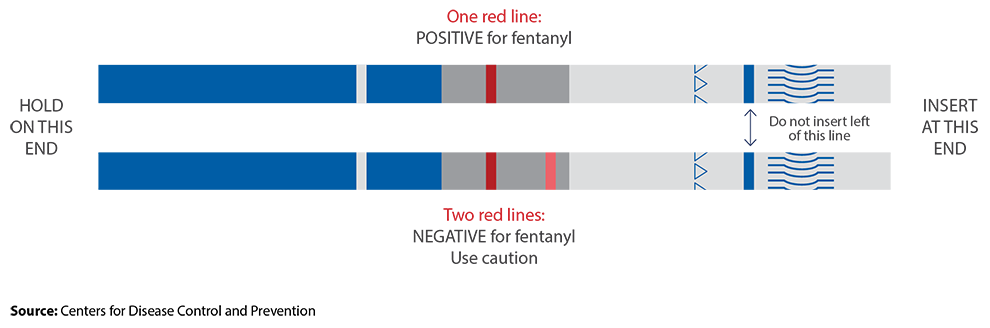

An individual may ingest fentanyl — which, even in small doses, is potentially deadly — without knowing it. The drug cannot be detected by sight, taste, smell or touch, and is now commonly mixed with illicit drugs such as heroin, cocaine and methamphetamine, as well as made into pills that resemble other prescription opioids, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

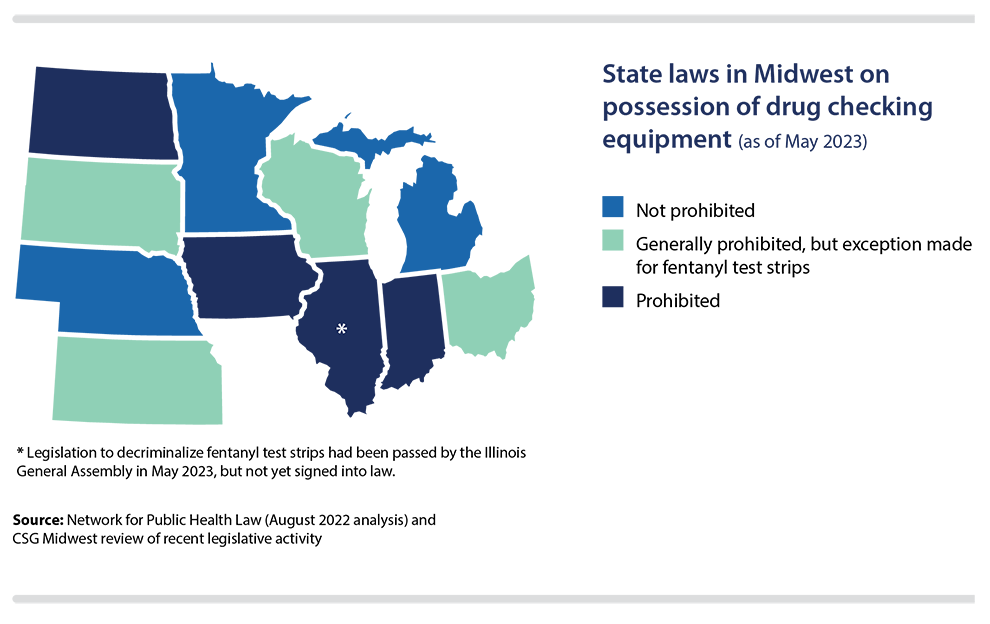

A test strip can be used to determine whether a drug is laced with fentanyl, and more U.S. states, including in the Midwest, are adopting laws to decriminalize the possession and/or distribution of these strips. Without such legislative action, fentanyl strips may be illegal under many states’ broader, longstanding prohibitions on drug paraphernalia and drug checking equipment, according to an August 2022 analysis by the Network for Public Health Law. The network’s study found, for instance, that every Midwestern state except Michigan and Nebraska had laws that generally bar the possession of drug checking equipment.

At the time of that analysis, states such as Minnesota and Wisconsin already had carved out exceptions for fentanyl test strips, and other state legislatures have done so in 2023. The network’s analysis from 2022 also found that states such as Illinois, Michigan, Minnesota, Nebraska, Ohio and Wisconsin have statutory language that allows for the free distribution of fentanyl test strips (or all drug checking equipment, in some cases).

Decriminalization of test strips

In 2021, with the passage of HF 63, Minnesota legislators added statutory language to remove fentanyl test strips from the state’s definition of illegal drug paraphernalia. Wisconsin took similar action in 2022 (SB 600), and as of May 2023, Kansas (SB 174), Ohio (SB 288) and South Dakota (HB 1041) were among the Midwestern states where decriminalization bills had been signed into law in 2023.

Also in 2023, Minnesota became the first U.S. state to legalize drug paraphernalia, including testing equipment and syringes. Those provisions were included in SF 2909, an omnibus measure signed into law in May.

Legislation to decriminalize fentanyl test strips has stalled, however, in some states. In Iowa, for instance, lawmakers cited concerns raised this year by law enforcement officials. “Almost unanimously, they asked us to pump the brakes on this,” Iowa Rep. Phil Thompson told the Iowa Capital Dispatch. “Their major concern … a lot of times, what we’re seeing in some of these states that have expanded it are getting false negatives on those counterfeit pills.”

Distribution of fentanyl test strips: Examples of 3 recent laws in Midwest

One option for states is to establish new laws or programs that allow for and/or facilitate the distribution of fentanyl test strips. Here are three examples from the Midwest.

North Dakota

HB 1163, enacted in 2021, added a section to an existing law that had authorized syringe or needle exchange programs. Specifically, HB 1163 outlines which supplies can be part of these syringe service programs; those supplies include drug test strips as well as the overdose-reversal drug naloxone.

Wisconsin

In October 2022, seven months after the Wisconsin Legislature decriminalized the possession of fentanyl test strips (SB 600), the state Department of Health Services announced that more than 120,000 of these strips had been distributed to tribal health clinics, county and municipal health departments, and other organizations. The department says drugs mixed with fentanyl are the leading cause of overdose deaths in Wisconsin.

Illinois

In Illinois, pharmacists, physicians and other health care professionals now have the legal authority to store and distribute fentanyl test strips as the result of HB 4556, a measure signed into law in 2022. In 2023, lawmakers passed HB 3203, which allows pharmacists and retailers to sell over-the-counter fentanyl test strips and also permits county health departments to distribute the strips free of charge. Also included in HB 3203: language eliminating fentanyl test strips from Illinois’ definition of illegal drug paraphernalia. The Illinois bill had not yet been signed into law as of early June.

Approach #2: Naloxone access as a harm reduction strategy

Naloxone is a proven life-saving drug. It can reverse a heroin, fentanyl and prescription opioid overdose as well as restore normal breathing within two to three minutes, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Many state laws, programs and investments aim to expand access to and the availability of naloxone. In separate summaries of laws across the country, the Network for Public Health Law and the Legislative Analysis and Public Policy Association point out several legal provisions that can impact access. Their work raises several questions for policymakers to consider about laws in their own states:

• Who should the state authorize to prescribe, dispense and/or administer naloxone? Should the authority to administer naloxone extend to laypeople? Should certain organizations (nonprofit and community health groups, for example, or state-authorized syringe access programs) be able to legally distribute naloxone?

• Is criminal, civil and/or professional immunity provided to individuals who prescribe, dispense or administer naloxone?

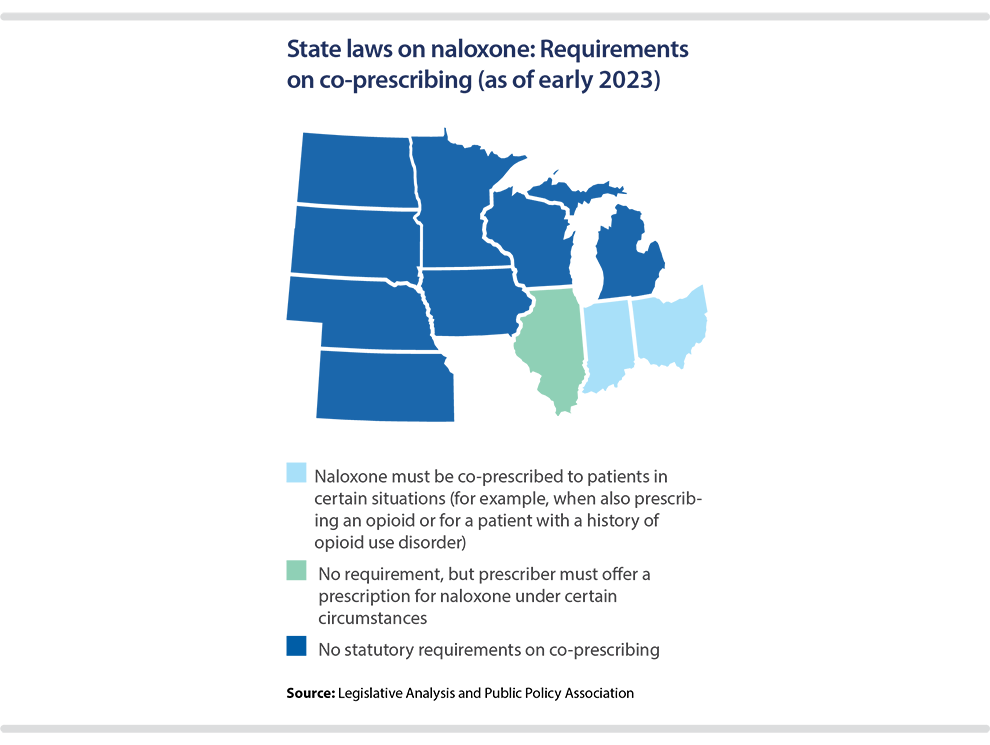

• Should the state require or encourage naloxone to be co-prescribed for certain individuals — for example, those being prescribed a prescription opioid or those with a history of opioid use disorder? (See map below.)

• Does state law allow naloxone to be prescribed to a person not necessarily at risk of an overdose, but who could be in position to help someone who is (for example, the family or friends of someone with opioid use disorder)?

• What requirements should be placed on insurers to cover naloxone or other overdose-reversal drugs? Are schools permitted and/or required to have naloxone available on site?

Examples of recent state activity in the Midwest on naloxone access

Illinois

Under a measure signed into law in 2022 (HB 4408), Illinois’ Medicaid program and private insurers soon will be prohibited from charging a copay for naloxone, if the drug is covered under their health plan. A prior Illinois law already required insurers to provide coverage for at least one opioid antagonist.

SB 2535, also signed into law in 2022, establishes a new requirement for pharmacists who dispense an opioid: they must inform the patient about the option to receive naloxone or another kind of opioid antagonist.

Along with these changes in the law, Illinois unveiled a $13 million plan two years ago to expand naloxone access, and as part of its broader Overdose Action Plan, the state is purchasing naloxone for community organizations, hospitals and clinics. Other strategies include having first-responders or law enforcement provide supplies of naloxone to the family and friends of people who have experienced an overdose, as well as installing naloxone vending machines or “rescue stations” in public places.

Ohio

In early 2023, Ohio officials announced plans to help public colleges and universities install emergency naloxone access cabinets on their campuses. Up to five of these cabinets are being offered at no cost to each school. The publicly accessible kits include boxes of naloxone along with instructions on how to use the opioid antagonist. The new Ohio initiative was made possible by lawmakers’ passage in 2020 of HB 341, a measure that allowed for greater naloxone distribution — both in terms of how it can be distributed and which groups can dispense it.

Another notable initiative in Ohio is Project DAWN, a network of opioid-overdose education and naloxone-distribution programs coordinated by the state Department of Health. DAWN stands for Deaths Avoided With Naloxone and is named in honor of a woman who died of an opioid overdose. Located across the state, Project DAWN programs distribute naloxone and provide training on how to prevent opioid overdoses.

South Dakota

Signed into law in March 2023, South Dakota’s HB 1162 authorizes employers to acquire naloxone or another opioid antagonist from a licensed health care professional and to make it available at their place of business. As part of the new law, the state Department of Health is charged with establishing training and instruction on how to administer an opioid antagonist. The employer would need to post instructions on how to administer the drug if he or she chooses to make it publicly accessible. Liability protections are included in the law for employers and workers.

Michigan

In 2019, Michigan lawmakers approved a package of bills (SB 200, SB 282-283 and HB 4367) allowing most government agencies (including public schools and libraries) to purchase and possess an opioid antagonist and to distribute it to trained employees. The measures provide immunity for good-faith administration of the drug, and are designed to encourage these government entities to keep an overdose-reversal drug on hand and for employees to use it when necessary.

Additionally, a 2022 law in Michigan (HB 5166) permits social service providers, nonprofit groups and other community-based organizations to distribute naloxone.

Iowa

In 2023, Iowa lawmakers established a new list of “secondary distributors”: entities that can be prescribed an opioid antagonist by a licensed health care professional and that are authorized to distribute it. The list includes police and fire departments, emergency medical services programs, school districts, behavioral health providers, county health departments, and the state Department of Health and Human Services. HF 595 includes immunity protections for these secondary distributors. When providing naloxone or another opioid antagonist, these distributors must “provide written instruction, which shall include emergency, crisis and substance use referral contact information.”

Minnesota

Entering 2023, Minnesota was one of 20 U.S. states (including most in the Midwest) that permitted schools to possess naloxone and school nurses to administer it. In 2023, Minnesota legislators became the first state in the Midwest (and one of only a handful in the United States) to require school districts to have a supply of naloxone at each of their school buildings. HF 2497 was signed into law in May. Each school building must have two doses of nasal naloxone available on-site, and the state commissioner of health is charged with developing training materials to help schools implement an emergency response plan.

Another new law (SF 2934) requires several other entities to carry an emergency supply of opioid antagonists — for example, “sober homes,” treatment programs for substance abuse, group housing, community corrections programs, and safe recovery sites.

The Minnesota Legislature allocated $3 million a year to establish these safe recovery sites. Naloxone distribution will be one of many services offered at these sites. (Other services include fentanyl drug testing, referrals to treatment and wellness programs, safe injection spaces and sterile needle exchanges.) Additionally, new state grants will go to “culturally responsive” community recovery programs.

Approach #3: Good Samaritan laws as a harm reduction strategy

Over the past decade, state legislatures across the Midwest have established and revised statutory language that provides legal immunity to individuals either experiencing or witnessing a drug overdose who reach out for medical assistance from law enforcement or other first-responders.

These measures are known as “good Samaritan” laws. Their intent: Save lives by ensuring that individuals are not dissuaded from seeking assistance out of fear of arrest or criminal prosecution for a crime that is discovered at the scene.

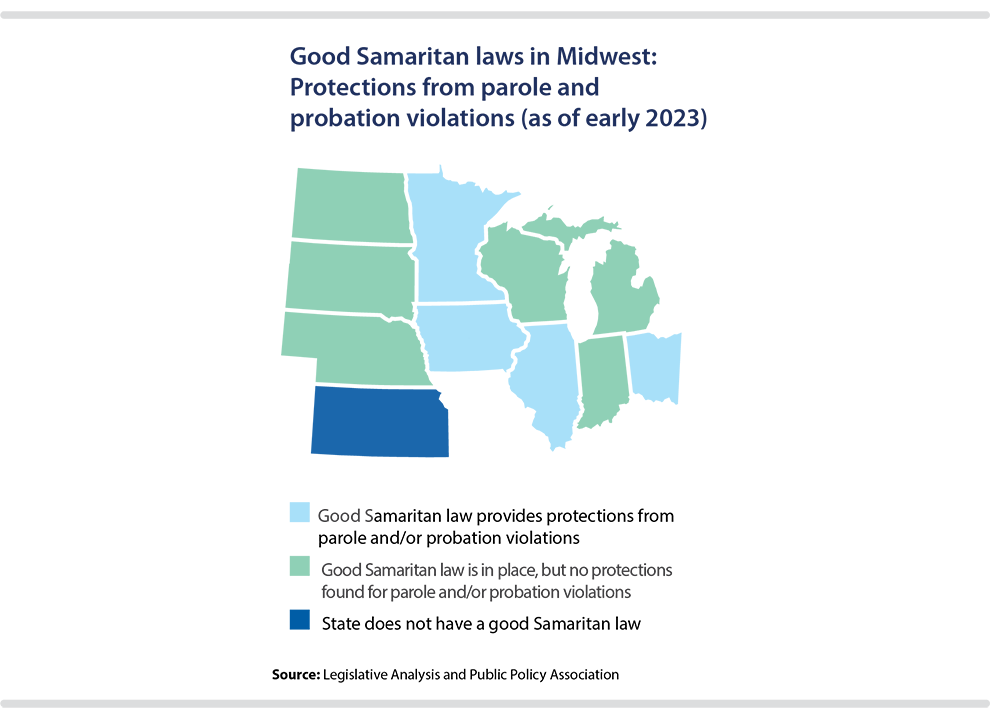

The extent of these protections can differ considerably from state to state. As of early 2023, every Midwestern state except Kansas had a good Samaritan law in place. Most commonly, the immunity from prosecution extends to certain or all types of drug possession, but not drug delivery, according to a 2021 analysis by the U.S. Government Accountability Office of all 50 U.S. states’ laws.

However, the GAO study did note that in Iowa, immunity applies to delivery as well if it “involved the sharing of the controlled substance without profit.” Wisconsin’s good Samaritan law only applies to immunity from prosecution, whereas the language in other Midwestern states protects individuals from arrest, charge and prosecution. (Authors of the GAO report note that some states specify that an individual may not be arrested, charged or prosecuted; others have different terminology but were still categorized as providing this immunity.)

Other variations in good Samaritan laws pose questions for policymakers to consider in their respective states.

- Should immunity be provided for all drug possession offenses, or only certain lower-level misdemeanor offenses?

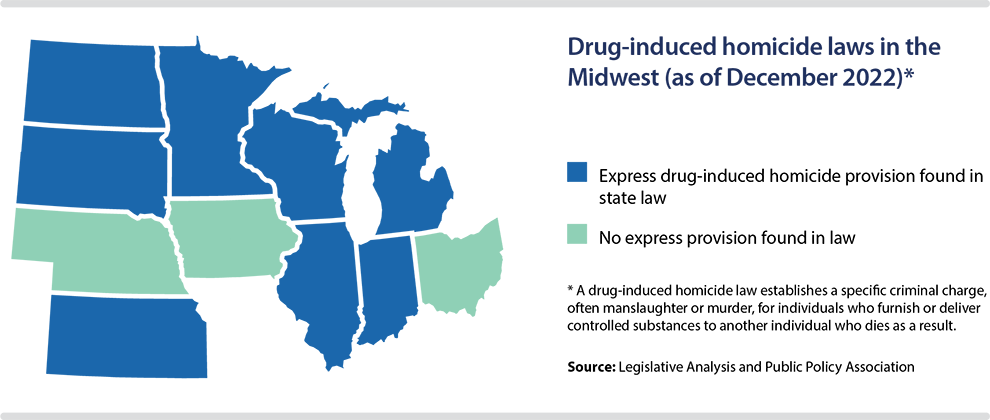

- Should good Samaritans have immunity from being prosecuted under a state’s drug-induced homicide law?

- Should specific requirements be placed on individuals reporting the overdose (staying at the scene, cooperating with authorities, etc.) in order for them to qualify for immunity?

- Should the law protect good Samaritans from facing sanctions due to violations of their probation and/or parole?

- Should immunity be provided for not only the person reporting the overdose, but the person experiencing the overdose as well?

- Should immunity be contingent on an individual receiving addiction treatment? (Ohio has such a requirement.)

- Should the actions of good Samaritans be considered a mitigating factor if they are sentenced for an offense for which immunity is not provided under the law, but that was discovered due to them reaching out for medical assistance? Minnesota’s statute has mitigating-factor language, for instance.

Two recent state actions in Midwest on good Samaritan laws

Ohio

As part of a comprehensive criminal justice measure, signed into law in early 2023, Ohio lawmakers tweaked their existing good Samaritan law in two ways. First, SB 288 adds immunity protections for violations related to the possession of drug paraphernalia. According to a 50-state summary by the Legislative Analysis and Public Policy Association, South Dakota was the only other Midwestern state not providing this protection as of December 2022. Second, Ohio now provides protections for good Samaritans who may have otherwise faced sanctions for probation- and parole-related violations.

Illinois

Three years after the fentanyl-related overdose death of 25-year-old resident Alex Green, Illinois expanded the reach of its existing good Samaritan law. Other people were with Alex at the time of his overdose but did not report it. The goal of “Alex’s Law” (HB 3445 of 2021) is to encourage individuals to seek medical assistance when an overdose occurs. It ensures that people who seek emergency assistance for an individual experiencing symptoms of an opioid overdose will not be arrested for any crime related to the use of drugs at the scene. One key provision: the granting of new legal protections that shield good Samaritans from being charged with a criminal killing under the state’s drug-induced homicide law.

Illinois’ good Samaritan law also provides protections against being charged with possession of drug paraphernalia or from any sanctions due to violations of parole and probation.

The funding of harm reduction strategies and the national opioid settlement

The distribution of fentanyl test strips and naloxone, along with the legal immunity provided under good Samaritan laws, often only are part of states’ harm reduction strategies.

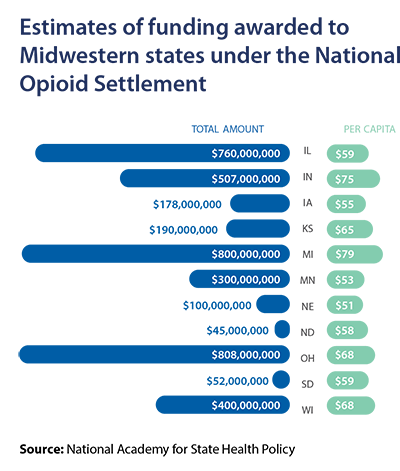

In implementing these strategies, states have several potential funding sources, including their own-source revenue; federal grants; and money from legal settlements with opioid manufacturers, distributors and retailers.

Michigan, for instance, is receiving $800 million from a nationwide opioid settlement with three pharmaceutical distributors and a drug manufacturer (AmerisourceBergen, Cardinal Health, McKesson and Johnson & Johnson). A three-bill package signed into law in 2022 (SB 993-995) provides a decision-making framework to guide how these funds will be used.

Subsequently, the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services announced initial plans to invest in a mix of recovery, treatment, prevention and harm reduction programs in fiscal year 2023. The funding of syringe service programs, which provide access to fentanyl test strips as part of their services, is included in Michigan’s investment of opioid-settlement dollars. Additionally, part of the money will support the department’s Naloxone Portal, which allows community organizations that distribute naloxone to request supplies of it from the state.

Prior to the nationwide settlement, Minnesota legislators passed in 2019 an opiate epidemic response bill (HF 400), under which newly established registration fees on prescribers, drug manufacturers and distributors are used to fight the state’s opioid epidemic. In FY 2023, $5.7 million in state grant funding from the Opioid Epidemic Response Advisory Council went to 12 organizations, including groups that distribute fentanyl test strips and naloxone as part of harm reduction services. In 2022, bipartisan legislation was signed into law (SF 4025) outlining how Minnesota will use the $300 million that the state is receiving from the nationwide opioid settlement.

Under the nationwide opioid settlement, states and localities will be awarded money over an 18-year period. At least 70 percent of the money must go to “opioid remediation efforts,” including investments in prevention, treatment, recovery and harm reduction.

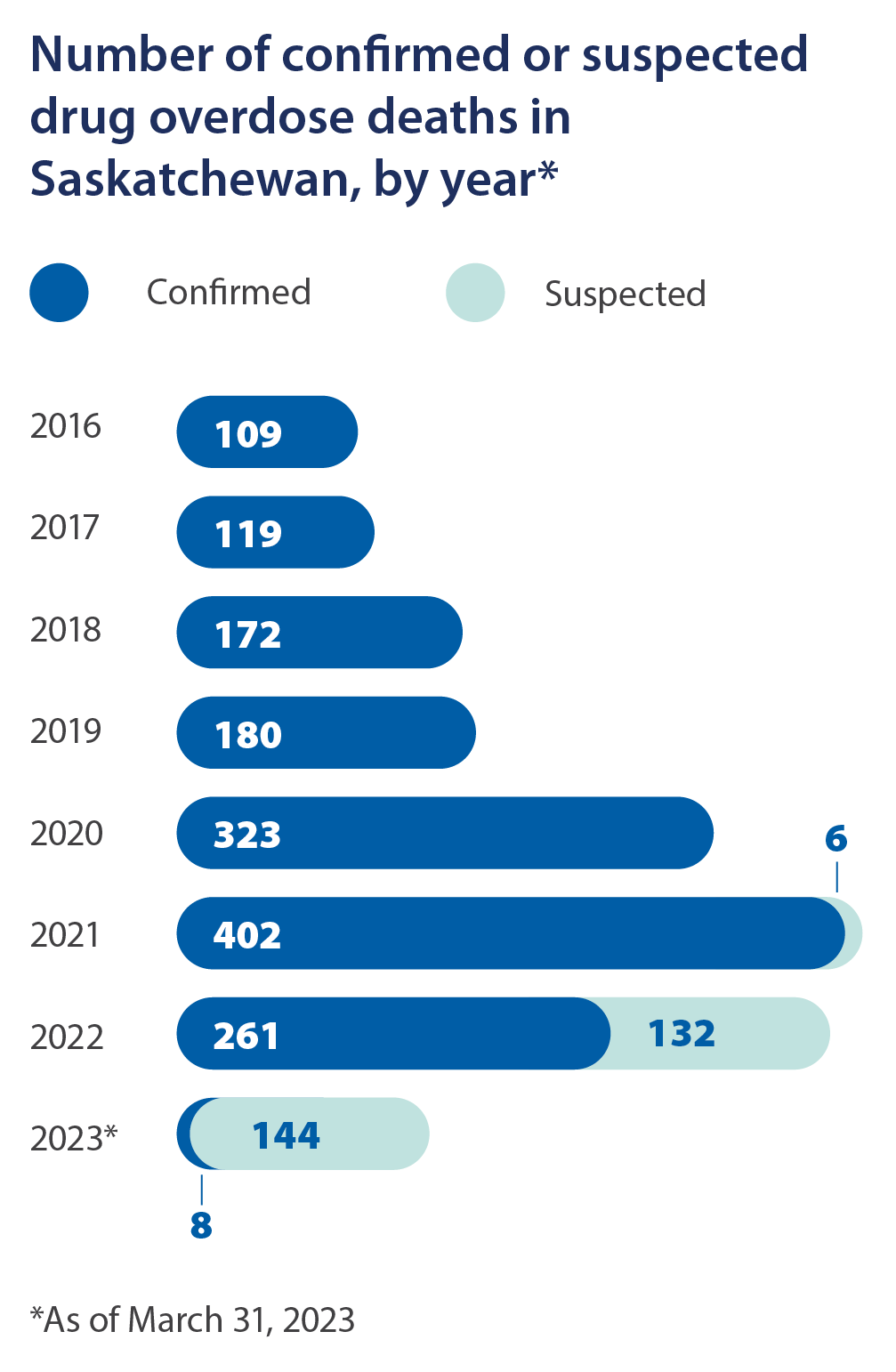

How Saskatchewan is expanding access to harm reduction services

The province of Saskatchewan is investing record levels of funding into mental health and addiction services, and part of that money is being used to establish or expand harm reduction programs that reduce drug overdose deaths. For example:

- Across the province, free take-home naloxone kits are available in more than 93 communities at more than 320 different sites. Health officials say the number of locations will continue to rise as the province expands its partnerships with community pharmacies.

- Fentanyl testing strips are made available throughout the province. Locations include hospitals, clinics, public health offices, community-based organizations and other facilities where overdose prevention, harm reduction or addiction support services are available.

- The province also has invested in a fleet of buses and vans that are equipped to provide wellness and harm reduction services. These mobile services help get trained professionals to places where they are needed most, and can operate when fixed harm-reduction sites are closed. The community wellness buses are used to distribute safer injection and safer inhalation equipment, provide take-home naloxone kits, offer drug testing services, and supply information on harm reduction resources.