By making most of new resources, states can build better pathways to recovery from substance abuse

Amid the despair of broken and lost lives due to a rise in the prevalence of substance use disorder (SUD), there is at least one glimmer of hope. States have more financial resources and tools to address SUD.

Amid the despair of broken and lost lives due to a rise in the prevalence of substance use disorder (SUD), there is at least one glimmer of hope. States have more financial resources and tools to address SUD.

More money is flowing to states through two federal grant programs: 1) the Substance Use Treatment, Prevention, and Recovery Services Block Grant; and 2) State Opioid Response grants. The National Opioids Settlement is providing new dollars as well, and revamped federal rules on Medicaid are offering states new options to meet the needs of higher-risk populations, including incarcerated individuals returning to their communities.

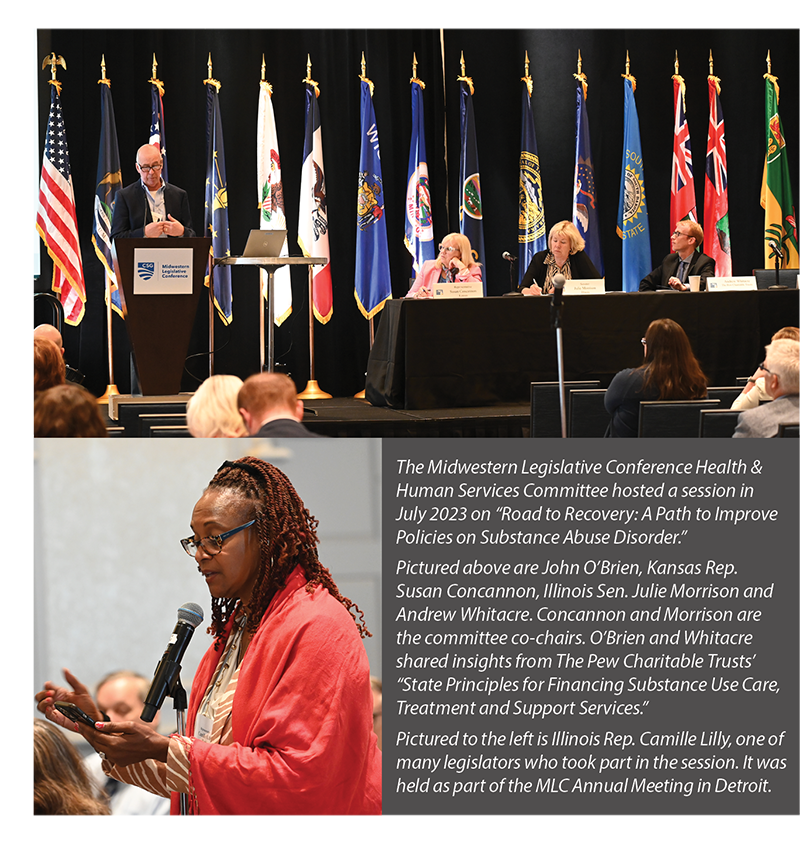

Making the most of these new funding and policy opportunities was the focus of a July session at the Midwestern Legislative Conference Annual Meeting. Organized by the MLC Health and Human Services Committee, the session provided legislators with a set of evidence-based principles to guide future decision-making.

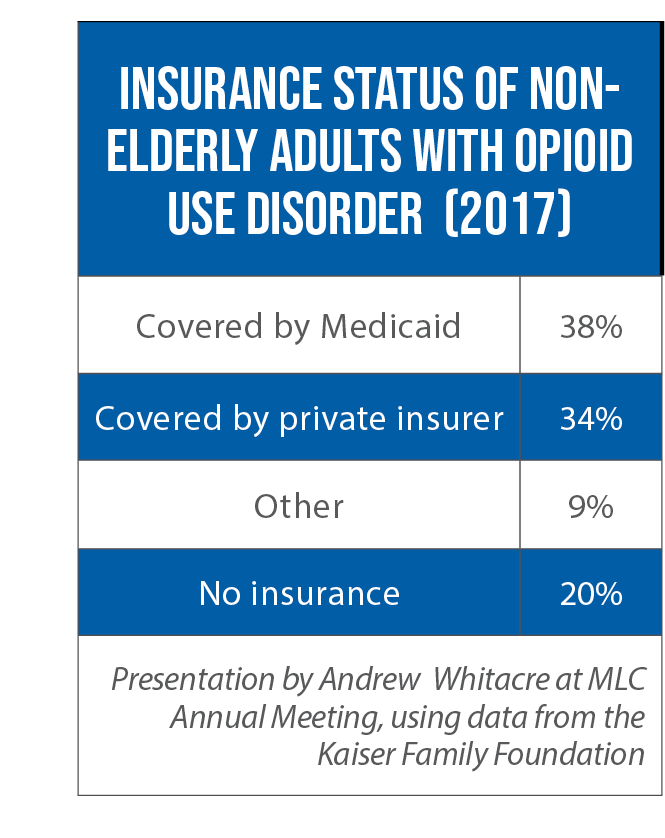

“Maximizing how the state is spending Medicaid dollars for opioid use disorder …. is really critical because it’s such a big payer,” said Andrew Whitacre, an officer with The Pew Charitable Trusts.

Among nonelderly adults with opioid use disorder, nearly 40 percent rely on Medicaid for their health insurance. A first step for legislators is to make sure their state’s Medicaid program is covering all evidence-based services allowed under federal law. But he said a second step is equally important: evaluate and, when necessary, boost reimbursement rates for services such as care coordination and medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder (the “gold standard” for treatment, he said).

“There are a number of states that do cover all those [SUD] services, but the pay is so low that no providers will participate in the network,” Whitacre noted.

“There are a number of states that do cover all those [SUD] services, but the pay is so low that no providers will participate in the network,” Whitacre noted.

Other obstacles stand in the way of access to effective treatment. Among them: the lack of an information technology infrastructure that would enable providers to establish proper billing systems, coordinate with other providers and evaluate practices. Non-Medicaid, flexible federal funds can be used to build up this infrastructure, Whitacre said, as well as address other areas not covered by the public insurance program. That includes harm reduction strategies such as the distribution of overdose-reversal drugs and fentanyl test strips, as well as funding for syringe service programs.

Opioid-settlement dollars can help in these non-Medicaid areas as well, and Whitacre said it’s critical for states to have guardrails in place to make sure these dollars fund new programs and services. Without such safeguards, the new money may simply be used to supplant current funding streams for existing initiatives.

New federal Medicaid waivers are another way of expanding access to care, John O’Brien, a former senior advisor for the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, said during the session. For instance, some states are taking advantage of a new opportunity to provide treatment services, via Medicaid, to individuals in the 90 days before they leave prison or jail and to continue that care upon re-entry. (An estimated 65 to 90 percent of individuals in jails and prisons have a substance abuse disorder.)

Likewise, a handful of states (California, Montana and West Virginia) are seeking waivers to pay for “contingency management” — providing incentives to individuals on the path to recovery (payments for a negative urine sample, for example). This treatment method has proven to be effective, O’Brien said.

The Pew Charitable Trusts’ 10 Consensus-Based Principles for Financing Substance Use Care, Treatment and Support Services

- Use Medicaid funds strategically to expand and sustain access to evidence-based substance use treatment and recovery support services.

- Direct flexible federal funds – to the fullest extent allowable – toward boosting infrastructure, harm reduction and recovery support services.

- Conduct an inclusive decision-making process for allocating opioid settlement funds and prioritize funds for investments in services and infrastructure needs not covered by Medicaid and other existing state/federal funding streams.

- Incentivize and sustain “no wrong door” approaches to substance use care, treatment, and support services.

- Ensure patients are placed in the most appropriate level of care, including considering non-residential, community-based substance use treatment and recovery support services.

- Address substance use treatment disparities at the point of care for historically marginalized groups and communities.

- Advance equitable access and outcomes for substance use care, treatment, and recovery support services among populations with multiple system involvement.

- Use data to drive effective, equitable care, and outcomes.

- Require specialty substance use treatment providers to provide evidence-based treatments, particularly MOUD.

- Bolster the substance use treatment and recovery support service network for children and youth.