States are well-positioned to handle an economic downturn, but long-term budget challenges remain

Shelby Kerns jokes that when she worked in the Idaho state budget office in the not-so-distant past, she “probably would have sold my soul” for year-over-year revenue growth of 5 percent.

Collectively, states got a lot more than that in fiscal years 2021 and 2022: inflation-adjusted increases of 12.7 percent and 7.6 percent, respectively. Several factors led to this unparalleled period in state finances — most notably, large amounts of federal dollars going directly to states as well as into the overall economy, and a temporary shift in consumer spending toward taxable goods and away from nontaxable services.

Collectively, states got a lot more than that in fiscal years 2021 and 2022: inflation-adjusted increases of 12.7 percent and 7.6 percent, respectively. Several factors led to this unparalleled period in state finances — most notably, large amounts of federal dollars going directly to states as well as into the overall economy, and a temporary shift in consumer spending toward taxable goods and away from nontaxable services.

“We have some pain on the horizon rolling off these one-time [federal] funds, and eventually we will have an economic downturn,” Kerns, now executive director of the National Association of State Budget Officers, said in July to the region’s fiscal leaders at the Midwestern Legislative Conference Annual Meeting.

“We have some pain on the horizon rolling off these one-time [federal] funds, and eventually we will have an economic downturn,” Kerns, now executive director of the National Association of State Budget Officers, said in July to the region’s fiscal leaders at the Midwestern Legislative Conference Annual Meeting.

But Kerns said states are better prepared than ever before to handle the pain.

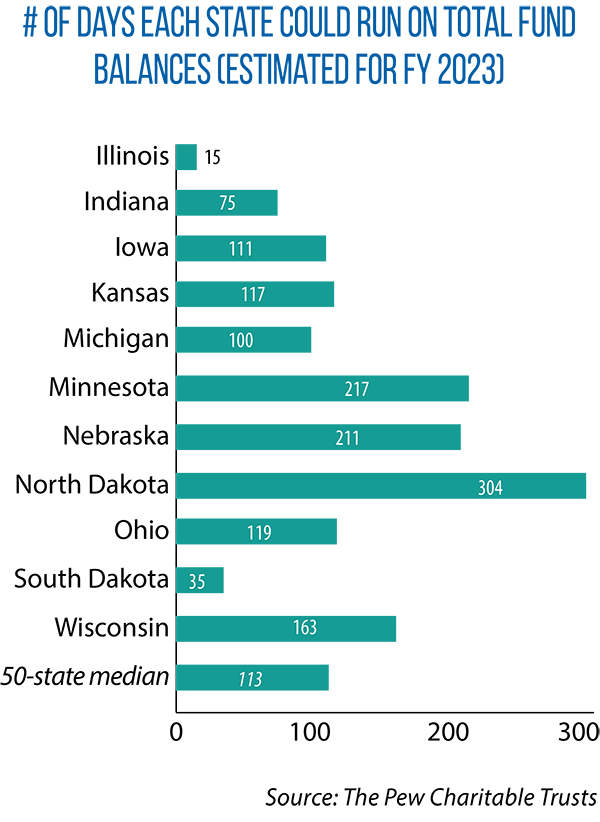

At one time, the goal of budget leaders was to have the size of state rainy day funds be equal to 5 percent of general fund spending. Estimates for FY 2023 among the 50 states showed rainy day funds on pace to be at 13.2 percent; that compares to 4.4 percent in FY 2009.

More than in years past, too, state leaders are recognizing the cyclical nature of state budget conditions, Kerns said, as evidenced by a change in the kind of tax-cutting measures being proposed by governors: In FY 2024, they called for more than $13 billion in tax cuts, but more than half of that amount only would have only a one-time, rather than recurring, impact on revenue.

“That’s a really important point and shows how strategic you all are being,” Kerns said.

In a separate presentation during the same session, Justin Theal of The Pew Charitable Trusts discussed the value of incorporating long-term fiscal strategies into ongoing budget discussions and negotiations. For example, by conducting budget “stress tests,” legislators learn how prepared their state is for a moderate or severe recession — and how large rainy day funds should be.

Likewise, fiscal leaders can get a better picture of potential structural deficits on the horizon by requiring budget projections to go beyond the next year or two, but instead as much as 10 years into the future.

Likewise, fiscal leaders can get a better picture of potential structural deficits on the horizon by requiring budget projections to go beyond the next year or two, but instead as much as 10 years into the future.

Over the longer term, Theal said, states face three major fiscal challenges, all of which are best addressed during times likes this — when revenue has been growing and surpluses are high.

One of those challenges is the need for more funding to respond to natural disasters. Most states have accounts for this purpose, he said, but little money is in many of them.

Second, about 30 percent of states’ future pension obligations are unfunded, though these numbers can vary widely from state to state. For example, Wisconsin’s and South Dakota’s systems are fully funded, whereas Illinois’ system is less than 50 percent funded. Indian a is among the states where a portion of budget reserves is now automatically directed toward paying down pension obligations, Theal said, while the Illinois, Kansas and Michigan legislatures recently authorized supplemental payments (above what is required by statute) to state or local pension systems.

A third long-term challenge is infrastructure, Theal said, with states facing unfunded liabilities of at least $1 trillion in deferred infrastructure maintenance.