Year of ‘right to repair’: Activity has included new state laws, private agreements covering farm equipment and many legislative proposals

As companies innovate and develop new products, those products become increasingly complex and computerized, and include more features. Contending that those features are proprietary, companies frequently restrict access to diagnostic tools or repair schematics, leaving consumers without the ability to repair the products they now own. Ideally, a free market would correct this problem without intervention.

Consumers simply wouldn’t buy products from manufacturers who fail to provide access to repair information. However, that approach gets muddled when the product is a durable good, designed to last many years.

The need for consumer protection also increases when product servicing is vertically integrated into an original equipment manufacturer’s business model. Some businesses may generate more revenue from servicing a product than from selling it. For example, Bloomberg News reported in 2020 that John Deere earned three to six times more in revenue from its sales on parts and servicing equipment than it earned from original sales.

The need for consumer protection also increases when product servicing is vertically integrated into an original equipment manufacturer’s business model. Some businesses may generate more revenue from servicing a product than from selling it. For example, Bloomberg News reported in 2020 that John Deere earned three to six times more in revenue from its sales on parts and servicing equipment than it earned from original sales.

How can consumers be better protected, including Midwestern farmers and ranchers whose operations rely on the purchase and repair of durable equipment?

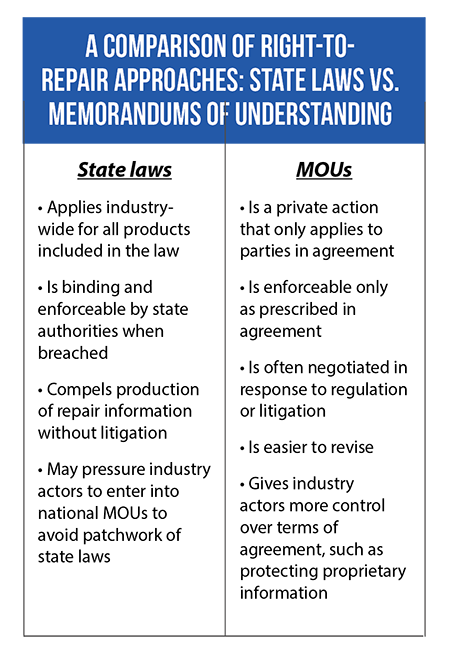

State right-to-repair laws and private-party memorandums of understanding (MOUs) are two options to ensure access to the diagnostics and data embedded in a whole range of products — from $800,000 tractors to small household appliances. Both methods have advantages.

Well-crafted repair laws or MOUs give owners and independent shops the information and tools necessary to fix products. When the law or MOU contains strong compliance provisions, competition within the aftermarket repair industry adds a second layer of consumer protection — a viable marketplace filled with choices for consumers on how to repair a product (including where the work is done and by whom).

First-in-the-Midwest law excludes farm equipment

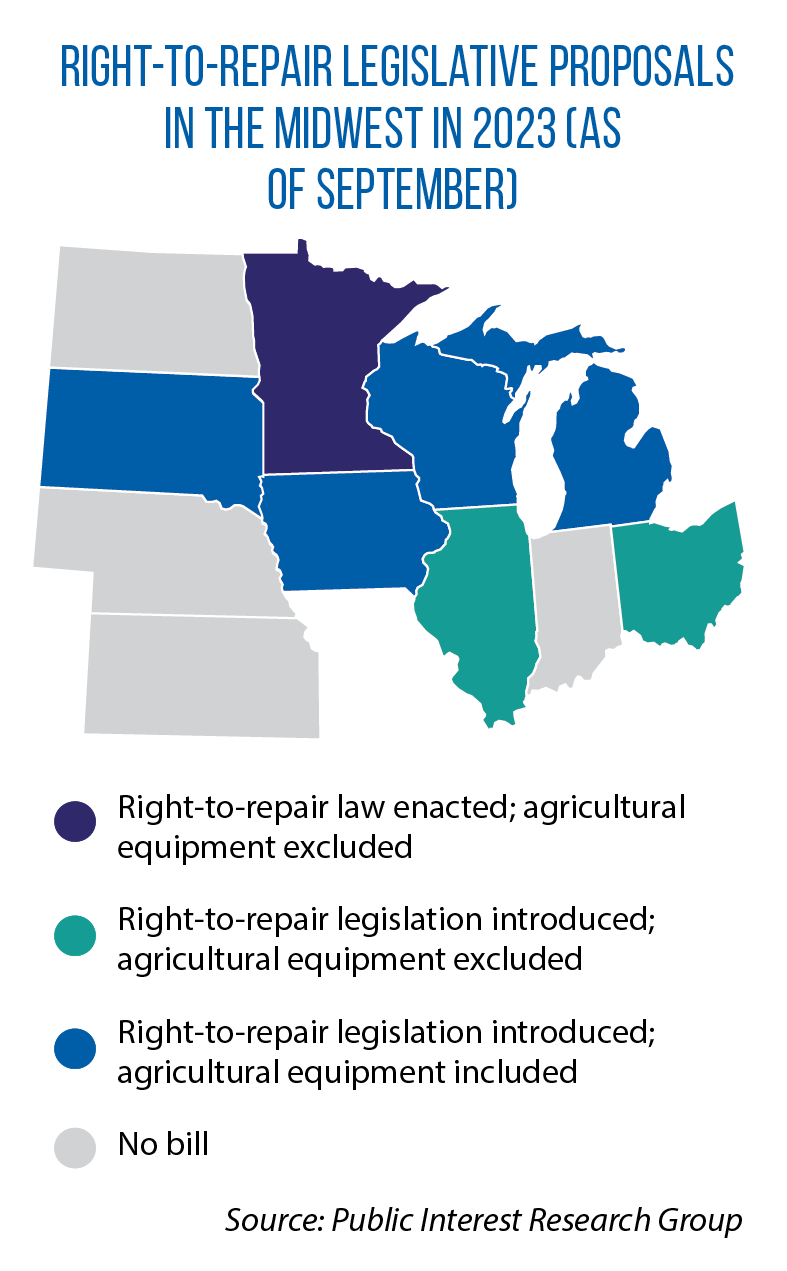

Over the past several years, there has been an uptick in right-to-repair legislative proposals, with measures introduced in 30 different states in 2023, according to the Public Interest Research Group (PIRG). Among them: Illinois’ HB 3593, Iowa’s HF 587, Michigan’s HB 4562, Ohio’s SB 273 and South Dakota’s SB 194.

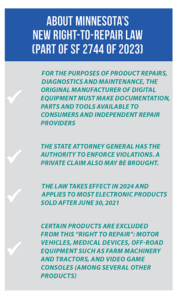

These state measures vary on which products are covered and which are exempted from a right-to repair statute. For example, a new Colorado law (HB 23-1011) includes farm equipment, while Minnesota’s recently enacted SF 2744 excludes these products.

According to Minnesota Sen. Robert Kupec, author of his state’s right-to-repair measure (part of the omnibus SF 2744), the exclusion of farm equipment was intentional. These products were removed from the bill due in part to a national MOU signed in early 2023 by the American Farm Bureau Federation and John Deere.

According to Minnesota Sen. Robert Kupec, author of his state’s right-to-repair measure (part of the omnibus SF 2744), the exclusion of farm equipment was intentional. These products were removed from the bill due in part to a national MOU signed in early 2023 by the American Farm Bureau Federation and John Deere.

In that MOU, John Deere agreed to provide diagnostic tools and information to farmers and independent repair shops. In exchange, the Farm Bureau agreed to discontinue right-to-repair lobbying efforts.

Other major agriculture equipment manufacturers such as Case, New Holland, AGCO, Kubota and CLAAS have since signed national MOUs with the Farm Bureau. The issue in the farm sector had been addressed, Kupec says, allowing Minnesota lawmakers to focus on other products and industries.

The right-to-repair provisions in SF 2744 ultimately received broad legislative support and have been hailed as one of the most comprehensive actions by a U.S. state to date. It also is the first right-to-repair law in the Midwest.

Pierce Bennett, policy director for the Minnesota Farm Bureau, says agricultural producers in the state support the national MOU between the Farm Bureau and John Deere. According to Bennett, members generally prefer resolutions through private-party measures, thus limiting the need for government regulation. And more specifically, the agreements allow farmers to buy access to software manuals, as well as the diagnostic tools needed to service their equipment.

Pierce Bennett, policy director for the Minnesota Farm Bureau, says agricultural producers in the state support the national MOU between the Farm Bureau and John Deere. According to Bennett, members generally prefer resolutions through private-party measures, thus limiting the need for government regulation. And more specifically, the agreements allow farmers to buy access to software manuals, as well as the diagnostic tools needed to service their equipment.

Previously, farmers had to wait for technicians to resolve issues, sometimes a costly delay during harvesting seasons. Still, as evidenced by the Colorado law, some legislators believe right-to-repair laws should cover farm equipment to provide stronger consumer protection.

Enforcing private right-to-repair agreements

An MOU, just like any law, is only as good as written, and state legislators should take a close look at the details of these new agreements, says PIRG’s Nathan Proctor, an advocate for state right-to-repair laws. Does the MOU contain provisions on enforcement? Does it apply to the entire industry? If so, Proctor says, it can be just as effective as a law.

He points to a 2014 agreement between the automotive industry and independent repair shops as an example of an effective MOU. Regarding farm equipment, though, Proctor says the MOUs have failed to include enforceability mechanisms. He also notes that while the American Farm Bureau is the largest organization of farmers, not all groups were included in the negotiations and some are still seeking state laws because of the lack of enforceability.

Another concern is the quality of the information and diagnostic tools made available. According to Proctor, PIRG investigators found instances of a company’s own technicians having better diagnostic tools and repair information than those made available to farmers and independent repair shops, placing these groups at a disadvantage.

When considering MOUs as a substitute for a right-to-repair law, Proctor adds, policymakers also should also consider differences among industry sectors and the legal environment. The automotive industry’s MOU worked because a Massachusetts law would have taken effect if the agreement had been breached. Perhaps even more significantly, Proctor notes, roughly 75 percent of the aftermarket car-repair industry is comprised of independent shops (non-manufacturers). In contrast, only a small percentage of farm equipment repairs are made independent of the manufacturer.

When considering MOUs as a substitute for a right-to-repair law, Proctor adds, policymakers also should also consider differences among industry sectors and the legal environment. The automotive industry’s MOU worked because a Massachusetts law would have taken effect if the agreement had been breached. Perhaps even more significantly, Proctor notes, roughly 75 percent of the aftermarket car-repair industry is comprised of independent shops (non-manufacturers). In contrast, only a small percentage of farm equipment repairs are made independent of the manufacturer.

The Farm Bureau maintains that its MOUs will compel manufacturers to produce meaningful repair information and will demonstrate their effectiveness over time. Bennett says he has not heard any complaints from Minnesota members regarding access to repair information.

Colorado’s right-to-repair law was signed in April. Starting in January, agriculture equipment manufacturers will be required to make repair information and tools available. Provisions in the farm sector’s new MOUs allow manufacturers to withdraw from these agreements upon enactment of state right-to-repair measures; however, none have done so since passage of the Colorado law.