Next-generation nuclear? States explore potential of small modular reactors being added to future electricity mix

Recent legislation and regulatory changes are clearing a path to develop a new generation of “small modular” nuclear reactors that advocates say could play a role in Midwestern states’ efforts to decarbonize their electric-power sectors.

Small modular reactors (SMRs) are a category that includes many different designs and technologies, all with one thing in common — individual reactors are designed to generate 300 megawatts or less and can connect to other modules to boost overall output.

Nuclear power already produces 45.5 percent of the country’s carbon-free energy, says Christine Csizmadia, senior director of state governmental affairs and advocacy for the Nuclear Energy Institute.

No SMRs are currently operational, though the first ones are scheduled to be built and online by early next decade in Texas and Wyoming.

Across the Canada-U.S. border, Saskatchewan’s electric utility, SaskPower, signed an agreement with GE Hitachi Nuclear Energy in January 2024 to advance plans for possible SMR development in the province.

A few months earlier, too, the Canadian federal government committed up to $74 million to the province to help pay for pre-engineering work, technical and environmental studies, and community engagement.

A final decision on whether to proceed with SMR construction in Saskatchewan is expected in 2029.

According to Csizmadia, compared to typical, larger reactors, SMRs are more economical and can be scaled to local needs. They also are less costly to build, take less time to complete, have fewer risks and provide more flexibility on siting, proponents say.

Given that many states — including Illinois, Michigan, Minnesota and Wisconsin — have stated goals or statutory requirements for 100 percent carbon-free energy by 2040 or 2050, Csizmadia says lifting any moratoria on new nuclear plant construction is the most important policy step states can take today.

“How are we going to meet those goals without something that operates 24-7 and is completely carbon free?” she says.

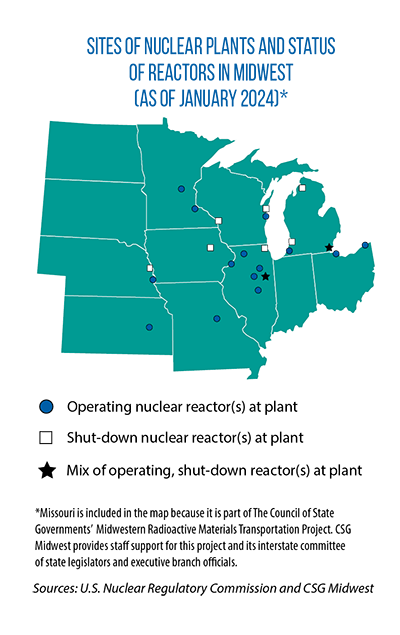

To date, Midwestern state actions range from lifting or modifying moratoria to studying the potential impacts on energy production, the economy and environment.

Some lawmakers also have proposed new SMR-related tax credits in hope of encouraging development.

Here is an overview of recent developments in the Midwest.

Details on new Illinois law

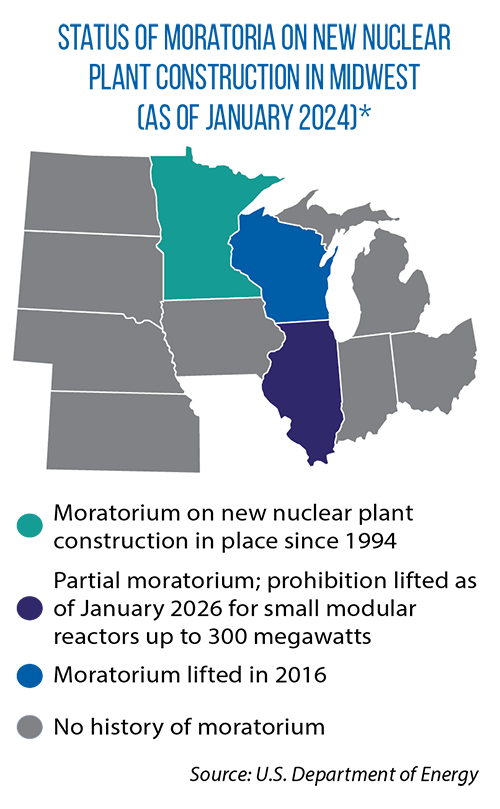

At one time, Illinois, Minnesota and Wisconsin had moratoria on new nuclear plants. Now, only Minnesota has a blanket ban in the Midwest, according to the U.S. Department of Energy.

Wisconsin lifted its moratorium in 2016 (AB 384), and at the end of 2023, Illinois partially ended its ban when legislators overwhelmingly approved HB 2473.

The new law allows for SMRs of up to 300 megawatts starting in January 2026. By that date, the state’s Emergency Management Agency and Office of Homeland Security must develop a regulatory framework for SMRs. The law also authorizes the governor to commission a study on issues such as:

• existing SMR technology and the future of research and markets for these advanced reactors;

• a risk analysis of these reactors;

• federal permitting and rules;

• the storage and disposal of waste from SMR facilities.

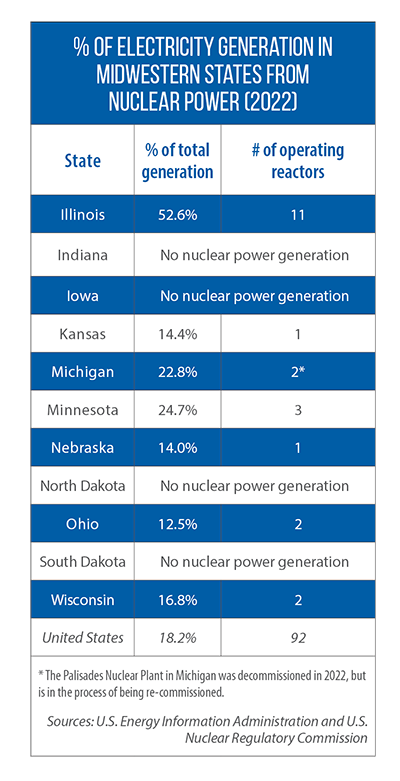

Illinois already gets 54 percent of its electricity from large nuclear plants, says Illinois Sen. Sue Rezin, the Senate sponsor of HF 2473.

Illinois already gets 54 percent of its electricity from large nuclear plants, says Illinois Sen. Sue Rezin, the Senate sponsor of HF 2473.

SMRs are a good alternative, she adds, because they can be built on the site of old coal or gas plants that already have power lines connecting them to the grid; there’s no need to build new power lines to a new site.

“It’s incredibly important for us to have them online so we can achieve our carbon goals [100 percent carbon-free] by 2045,” she says.

The new law is a revised version of a Rezin-sponsored bill that Gov J.B. Pritzker vetoed in August 2023. At the time of his veto, the governor had cited an “overly broad” definition of advanced reactors as well as the lack of a regulatory framework.

Midwest states studying future of nuclear power

Indiana lawmakers passed SMR-related bills in both 2022 and 2023.

The first measure, SB 271 from 2022, defines small modular reactors as “clean energy projects” and makes them eligible for financial incentives. That law also required utility regulators to adopt new rules governing SMR projects. The second measure, SB 176 of 2023, raised the power rating definition for SMRs from 350 MW to 470 MW.

In Michigan and Ohio, recent new laws and legislative appropriations have those states taking a closer look at the potential next generation of nuclear energy. Whether SMRs are part of that future remains to be seen.

Ohio’s budget (HB 33) creates a new Nuclear Development Authority. This nine-member, governor-appointed authority is charged with improving nuclear research and development in Ohio, and making the state a “leader in the development and construction of new-type advanced nuclear-research reactors.”

In 2022, Michigan legislators directed the state’s Public Service Commission to hire an outside consultant to study the state’s nuclear energy generation and potential, including SMRs. (HB 6019 included $250,000 for that study.)

A December 2023 draft report says nuclear energy is necessary to meet Michigan’s new goal of 100 percent carbon-free energy by 2040.

A final report is due to the Legislature in April.

Michigan Rep. Pauline Wendzel is proposing another policy option to advance SMRs: tax incentives. Under her bill, HB 4753, the state would provide a corporate tax credit equal to 15 percent of the costs related to SMR research, development or design.

Michigan Rep. Pauline Wendzel is proposing another policy option to advance SMRs: tax incentives. Under her bill, HB 4753, the state would provide a corporate tax credit equal to 15 percent of the costs related to SMR research, development or design.

“This has to be the future,” says Wendzel, who has two traditional nuclear power plants in her district. “Michigan has the highest number of engineers per capita, and we’re always looking for ways to stay ahead of the curve and attract that talent here. This just seemed to fit that perfectly.”

SMR measures also have been proposed this biennium in at least two other Midwestern states:

• Minnesota’s HF 3002/SF 3120 calls for a study of various aspects of SMRs. For example, what impact could they have on the state’s power grid, environment and economy? What laws or rules would need to be changed to allow for SMR construction and operation?

• Two Nebraska measures (LR 21 and LR 178) call for studies examining the feasibility of SMR projects.