Telehealth, post-pandemic: States face decisions on what to reimburse through Medicaid, as well as what to require of private insurers

Nebraska Sen. Tom Brewer represents a legislative district in the north central part of the state that stretches 300 miles long and 200 miles wide.

“There are only four locations with a hospital,” he says.

Miles and miles also separate a patient from the nearest provider in all kinds of health care areas and specialties; it’s a geographic and health care reality that his district shares with other rural areas in the Midwest.

The problem is not new, and telehealth has long been identified as a way to help close gaps in health care access. However, it had failed to gain widespread use until the COVID-19 public health emergency, which necessitated a rapid implementation and related policy changes (either temporary or permanent).

Since then, Brewer and other lawmakers have been looking at ways to sustain and expand telehealth for rural and urban constituencies alike.

What is telehealth?

Mei Kwong, executive director of the Center for Connected Health Policy, says it should not be thought of as a “service in and of itself; rather, it is a mode of health care delivery.” Within the broad definition of telehealth, too, there are distinct applications or modalities, such as the use of live video, “store and forward” or remote monitoring (see table for definitions). Link to Center for Connected Health Policy state policy trends.

Mei Kwong, executive director of the Center for Connected Health Policy, says it should not be thought of as a “service in and of itself; rather, it is a mode of health care delivery.” Within the broad definition of telehealth, too, there are distinct applications or modalities, such as the use of live video, “store and forward” or remote monitoring (see table for definitions). Link to Center for Connected Health Policy state policy trends.

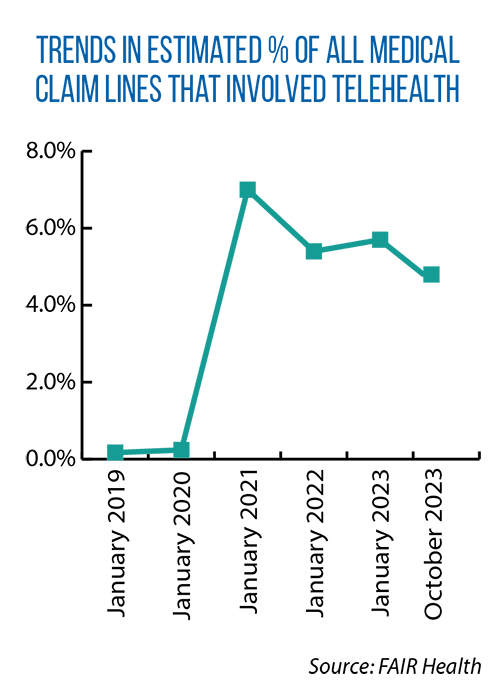

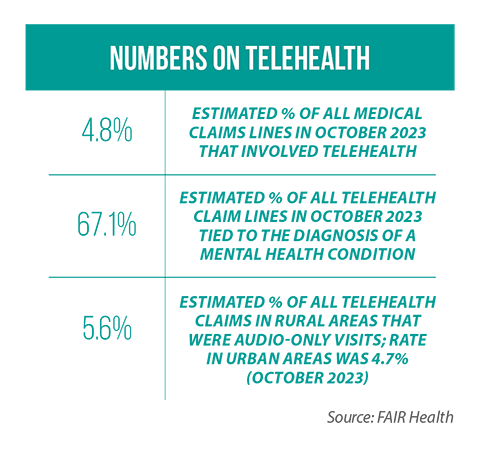

FAIR Health, a nonprofit organization that tracks privately billed health insurance claims, reports that in January 2020, only 0.24 percent of all privately itemized claims included a telehealth component. By 2021, that figure had spiked to 7 percent.

As of November 2023, the rate of claims including a telehealth component was 3.5 percent in the Midwest and 5.1 percent nationally. Link to FAIR Health telehealth tracker.

‘Didn’t sit right with me’

One factor impacting access to and the use of telehealth-based care: payment parity. In Nebraska, Sen. Brewer began hearing from constituents who were paying more for telehealth visits than in-person visits. That is because insurers were not required to reimburse providers at the same rates for virtual visits as in-person visits. Patients were left paying the difference.

“That didn’t sit right with me,” Brewer says. People wanted access to telehealth-based care, he adds, and health care professionals were willing to provide it.

Brewer introduced a payment-parity law in 2023, and LB 296 ultimately passed the Legislature with unanimous approval.

Brewer introduced a payment-parity law in 2023, and LB 296 ultimately passed the Legislature with unanimous approval.

Under this new Nebraska law, the reimbursement rate for any telehealth service must be the same as for a comparable in-person health care service. LB 296 applies to any licensed provider who also offers “in-person services at a physical location in Nebraska or is employed by or holds medical staff privileges at a licensed facility” in the state.

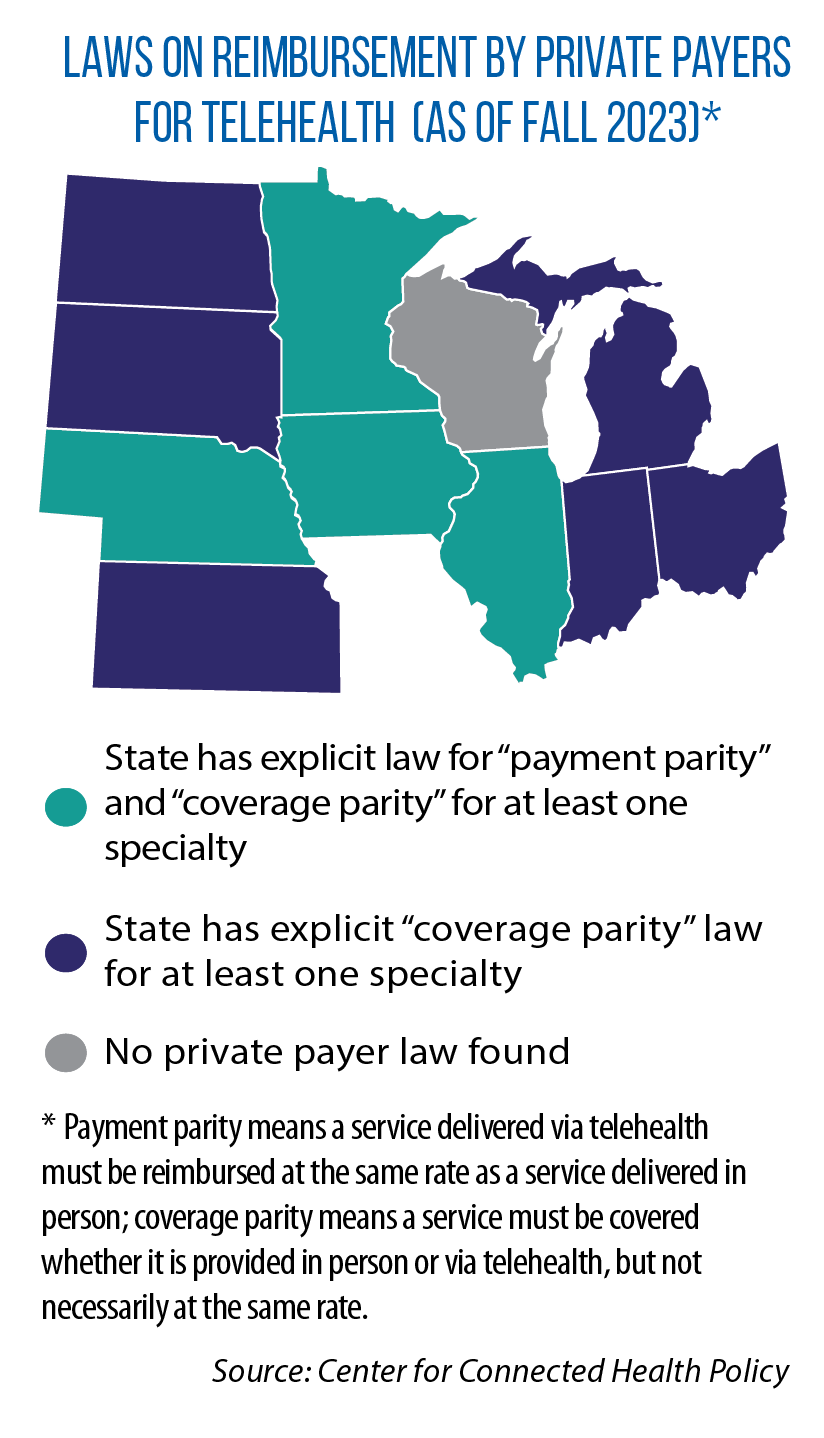

As of late 2023, Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota and Nebraska were among the 24 U.S. states with payment-parity laws, according to the Center for Connected Health Policy.

In testimony last year to the U.S. Senate Finance Committee, Dr. Chad Ellimoottil, the medical director of virtual care at the University of Michigan, identified payment parity as a key component to sustaining the availability of telehealth services, post-pandemic.

The American Medical Association has said, too, that if compensation rates are lower for telehealth services, physicians may choose to stop offering them.

Another important state policy decision involves Medicaid coverage of telehealth.

In the Midwest, all states provide Medicaid reimbursement for certain modes of telehealth, but not necessarily all of them. For example, the Center for Connected Health Policy says that as of fall 2023, Medicaid programs in Kansas and Nebraska were paying for live-video services, but not store and forward (see table).

Efficacy of telehealth

For policymakers, the continuation of state-based Medicaid reimbursement for telehealth or the adoption of payment parity will depend in part on assurances that telehealth works.

“Despite the extraordinary amount of research produced over a short amount of time, gaps in knowledge remain,” noted authors of a November 2023 study.

“Despite the extraordinary amount of research produced over a short amount of time, gaps in knowledge remain,” noted authors of a November 2023 study.

That study, “Telehealth Outcomes and Impact on Care Delivery,” was done for the nonprofit, philanthropic California Health Care Foundation.

While acknowledging the many unknowns, the authors do point to promising outcomes in certain specialties where telehealth has been closely studied.

For example, a “preponderance of the evidence” shows that live-video services are just as effective as in-person care in treating mental health conditions, including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Additionally, hybrid care, a mix of telehealth and in-person services, appears to be just as effective as in-person care alone for patients suffering from rheumatoid arthritis or in need of reproductive health or behavioral health services.

Researchers noted, too, that live video and in-person visits resulted in the same amount of utilization of other health care services after an initial treatment in areas such as urology, infectious disease, diabetes and postsurgical services.

With states largely making telehealth expansion permanent for Medicaid, Kwong says, it may place pressure on the federal government to do the same for Medicare. Several telehealth expansions in this program are set to expire by year’s end. According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, one in three rural adults is enrolled in Medicare.

The broadband connection

When the pandemic hit, Brewer says, his rural communities in Nebraska were ready for the shift to telehealth. His district had made good use of federal grants, as well as other public and private investments, to bring fiber optic cables and high-speed connectivity to its many small towns, farms and ranches.

When the pandemic hit, Brewer says, his rural communities in Nebraska were ready for the shift to telehealth. His district had made good use of federal grants, as well as other public and private investments, to bring fiber optic cables and high-speed connectivity to its many small towns, farms and ranches.

In areas of the country or individual residences that still lack broadband, audio-only telehealth services remain an option.

Every state in the Midwest has modified its respective Medicaid plans to allow for the reimbursement of audio-only telehealth. Whether those changes are temporary or permanent, however, varies from state to state.