States are reimagining child welfare policy, funding to address what some national experts view as a ‘design flaw’ in the traditional system

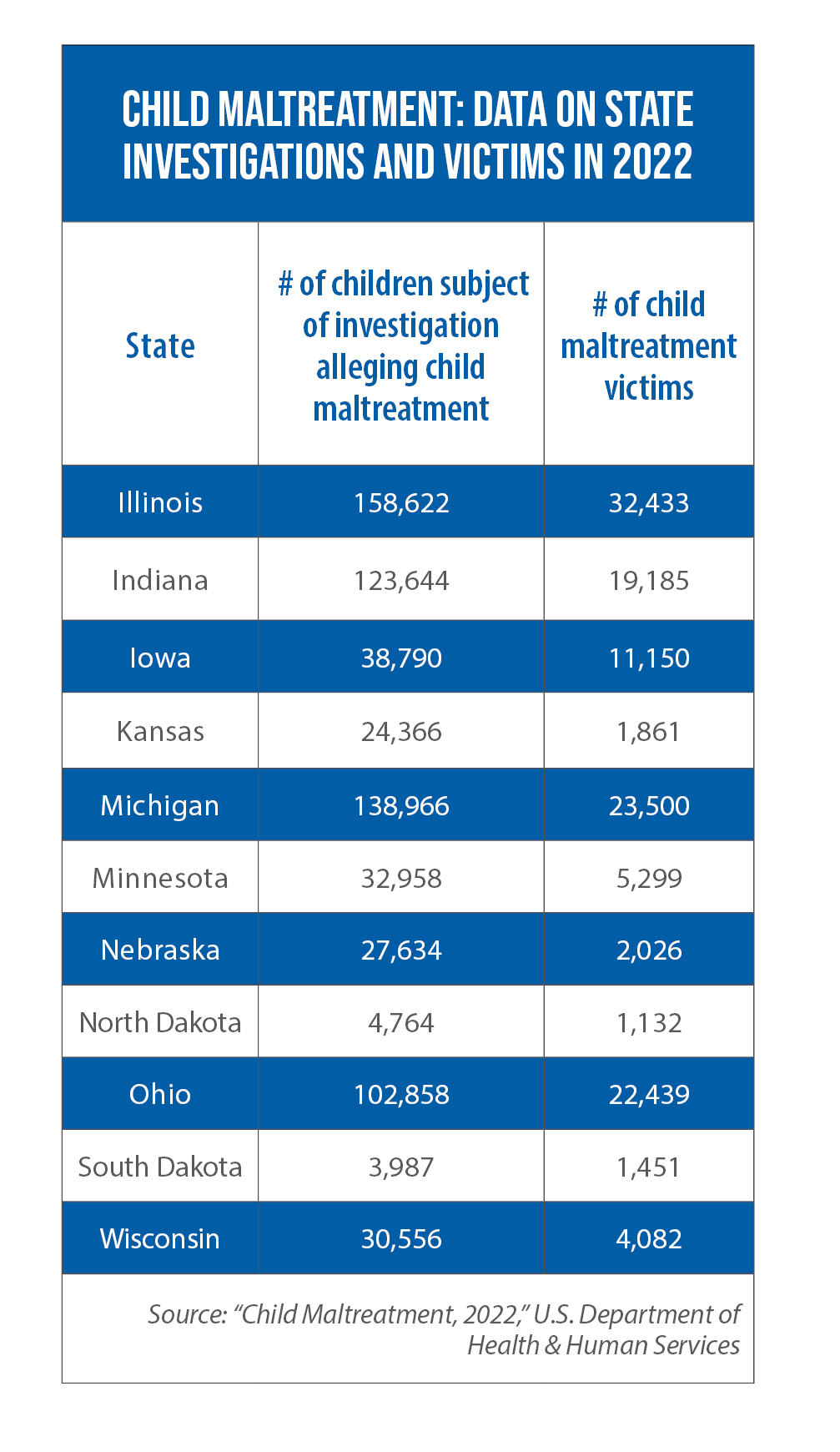

In 2022, the last year of available federal data, state child protection services (CPS) received an estimated 4.3 million referrals alleging child maltreatment. The number of children involved in those referrals: about 7.5 million.

Ultimately, though, most of these young people and their families did not receive any CPS-related supports or services.

“Families who come [to the attention] of child welfare have one set of needs, and they come to a system that is designed to do something else,” says Katie Rollins, a policy fellow at the University of Chicago’s Chapin Hall.

“Families who come [to the attention] of child welfare have one set of needs, and they come to a system that is designed to do something else,” says Katie Rollins, a policy fellow at the University of Chicago’s Chapin Hall.

According to Rollins, that “something else” has been to investigate and, when deemed necessary, place abused or neglected children in foster care.

David Sanders, another leading expert on state child welfare policy, says this traditional model is akin to a health system exclusively offering emergency care, with little or no capacity to deliver preventative services.

“It’s as if right now the only thing that’s offered is an ER visit, while what people really need is primary care,” says Sanders, executive vice president of systems improvement for Casey Family Programs. “That’s where the reimagining [of child welfare policy] has to occur. Many families who need help are not getting it now. All they’re getting is an investigation.”

Yet Sanders also sees reason for hope.

States are restructuring their systems in ways that invest in upstream services to prevent CPS involvement, that focus on keeping at-risk or in-crisis families together, and that provide more supports for kinship caregivers.

This shift is occurring in part because of changes in federal law, including the Family First Prevention Services Act of 2018 and the new policy and funding opportunities that it provides to states.

“It’s one of the most exciting things that’s happened in child protection over the past 50 years,” Sanders says

Opening new doors, narrowing others

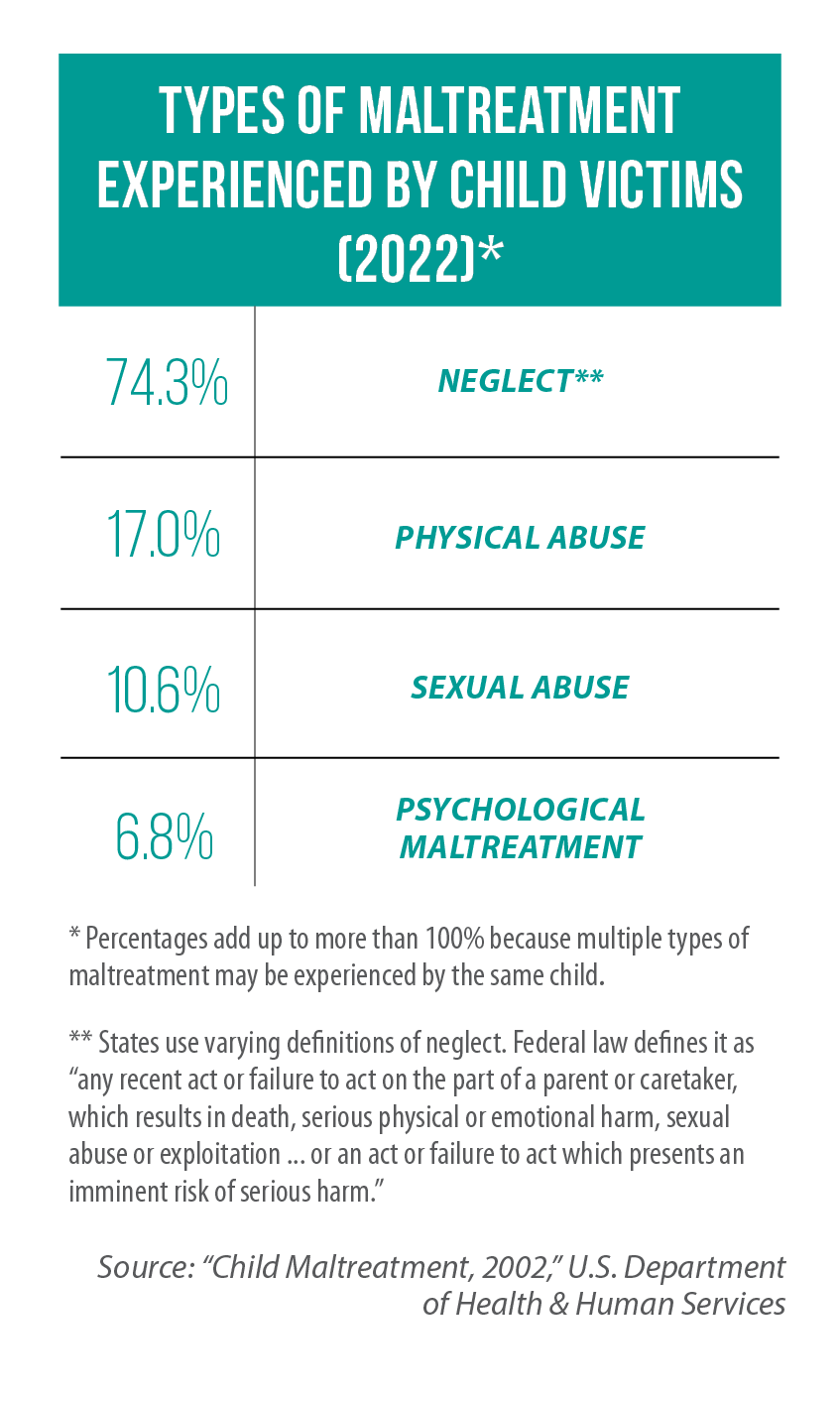

In an April 2024 study, Rollins and her Chapin Hall colleagues provide a framework for states to fix what they see as a longstanding “design flaw.” They envision a system in which child protective agencies only get involved in the most serious cases of abuse and neglect: Narrow that “front door,” while also opening up new opportunities for families to get help through home-visiting programs, services for behavioral health or substance abuse disorder, housing and child care assistance, and concrete economic supports.

“Before things become a crisis, we might be able to prevent many families from being involved in the child welfare system at all,” says Yasmin Grewal-Kök, also a policy fellow at Chapin Hall, who has written about the value of concrete economic supports in reducing child maltreatment and improving overall outcomes.

“Before things become a crisis, we might be able to prevent many families from being involved in the child welfare system at all,” says Yasmin Grewal-Kök, also a policy fellow at Chapin Hall, who has written about the value of concrete economic supports in reducing child maltreatment and improving overall outcomes.

Of those 4.3 million referrals in 2022 alleging child maltreatment, about half were “screened out” by CPS agencies, meaning the referral did not lead to an investigation or report from child protective services. But many of these “screened out” families and children often still need help, Rollins and Grewal-Kök say, and the referral itself can and should connect them to services.

About half of these referrals are “screened in,” involving an estimated 3.1 million children nationwide.

When a subsequent investigation does not find child abuse or neglect, post-response services for the child occur about 23 percent of the time. In referrals and investigations that lead to a finding of child abuse or neglect, 54 percent of child victims receive post-response services.

According to Rollins, these numbers point to a missed opportunity for states.

“Young people are struggling to find the supports they need in their communities, in their schools,” she says. “And when families are unable to handle those needs and unable to get the supports they need, kids too often end up in the child welfare system.

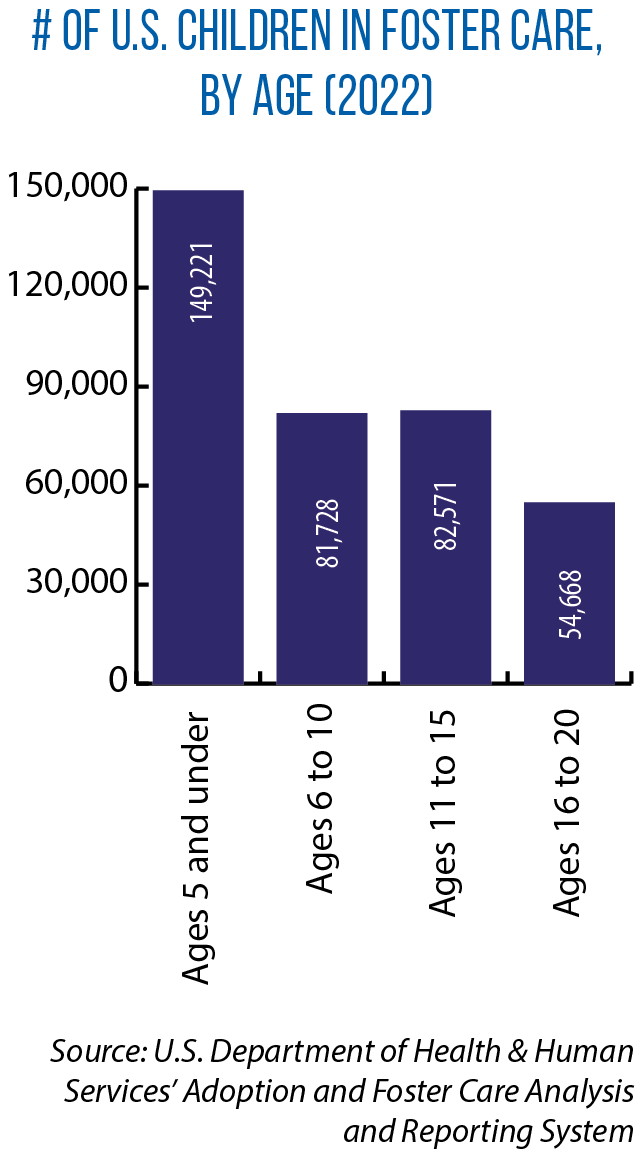

“And then those young people too often end up in the deep end of the system — in foster care, in congregate care and aging out.”

Indiana’s ‘community pathways’ model

Indiana often is cited as one of the states leading the way in “reimagining” child welfare policy since federal adoption of the Family First Prevention Services Act. In 2019, Indiana legislators passed HB 1001, which restructured how the state pays for family preservation services. The state implemented a per-diem payment model (vs. fee-for-service) to improve the coordination of services and accountability through a single provider, as well as to ensure the use of evidence-based interventions.

Indiana’s Family Preservation Services program is for families with a substantiated case of abuse or neglect. The Department of Child Services, though, determines that with appropriate home- and evidence-based interventions, the child can be safely cared for in the home. Early results show that the program has reduced rates of future child maltreatment.

Indiana’s Family Preservation Services program is for families with a substantiated case of abuse or neglect. The Department of Child Services, though, determines that with appropriate home- and evidence-based interventions, the child can be safely cared for in the home. Early results show that the program has reduced rates of future child maltreatment.

Additionally, Indiana is an early implementer of a “community pathways” model under the 2018 federal law. Families that have certain risk factors for future foster-care involvement are identified and made eligible for Healthy Families Indiana — home-visiting services that provide parents with hands-on education and supports and that connect them to community-based resources.

Notably, these upstream services are provided prior to any child welfare involvement at all. And federal funding is available through the Family First Prevention Services Act.

“Families are getting help in the community, with resources that in the past only would have gone toward an investigation or placement of children,” Sanders says.

More help for formal and informal kin caregivers

Another option for states: boost support for kinship caregivers.

Another option for states: boost support for kinship caregivers.

In 2022, with the passage of SB 3853, Illinois legislators initiated a pilot program to expand services for family members who are caring for the child of a relative. This includes home visiting, parent mentoring, and customized case management.

Earlier this year, Michigan became the first U.S. state to get federal approval of a plan to establish a separate, simpler licensing standard for kin caregivers. As part of the plan, too, the state will provide kin caregivers with the same level of financial assistance that any other foster care provider would receive.

Rollins says states also can do more to help informal kin caregivers, those individuals providing for children without formal involvement by the child welfare system.

“Many times these are economically fragile families, and it’s often the grandparents, who are likely to be on a fixed income, who now need to care for the child,” she says. “They’re often not eligible for supports and services they need, and that can lead the caregiving arrangement to be disrupted.”

In Ohio, though, these informal kin caregivers are explicitly eligible for assistance under the state’s Kinship and Adoption Navigator Program.