Keeping the ‘lights on, beer cold, water warm’

Reliability of grid will depend in part on how states respond to changes in the economy, energy mix and policy environment

Caught between rising demand for electricity, the retirement of old generating plants and the slow pace of construction of new transmission lines, the Midwest’s electrical grid is in a perilous situation, a panel of energy and utility experts told legislators in July.

Ohio Sen. Bill Reineke, chair of the Midwestern Legislative Conference, helped organize and host the plenary session at the MLC Annual Meeting (which was held separately from the work done by the MLC’s Energy & Environment Committee).

Leading and moderating it was Tony Clark, a former North Dakota state legislator who also has served as a member of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission and as chairman of the North Dakota Public Service Commission.

“Today’s topic can get weedy really fast,” said Clark, now a senior advisor to the law firm Wilkinson, Barker, Knauer, LLP. “It’s one of the more complicated ones [that] state policymakers deal with.”

States’ three regulatory models

As a starting point, Clark described the three types of regulatory models used by states to govern electricity markets: traditional, fully restructured and hybrid.

Sixteen U.S. states, but none in the Midwest, have what would be classified as a purely traditional model, he said: one vertically integrated utility controls generation, transmission (the high-voltage lines from generating plants) and distribution (the wires to homes and businesses) as part of a state-regulated monopoly.

In contrast, Illinois and Ohio have fully restructured, deregulated electricity systems. (Michigan often is identified as a “partially restructured” market.) This means that the utilities “unbundle” generation, transmission and distribution, and retail electricity markets are open and competitive. Distribution is regulated by the state, generation and transmission by FERC.

All other states in the region, Clark said, have some kind of hybrid system, with a regulatory framework that is part traditional, part restructured.

Four pressures on the grid

Concern over reliability is common across many states, regardless of the regulatory model, and Clark said much of it comes from a confluence of factors.

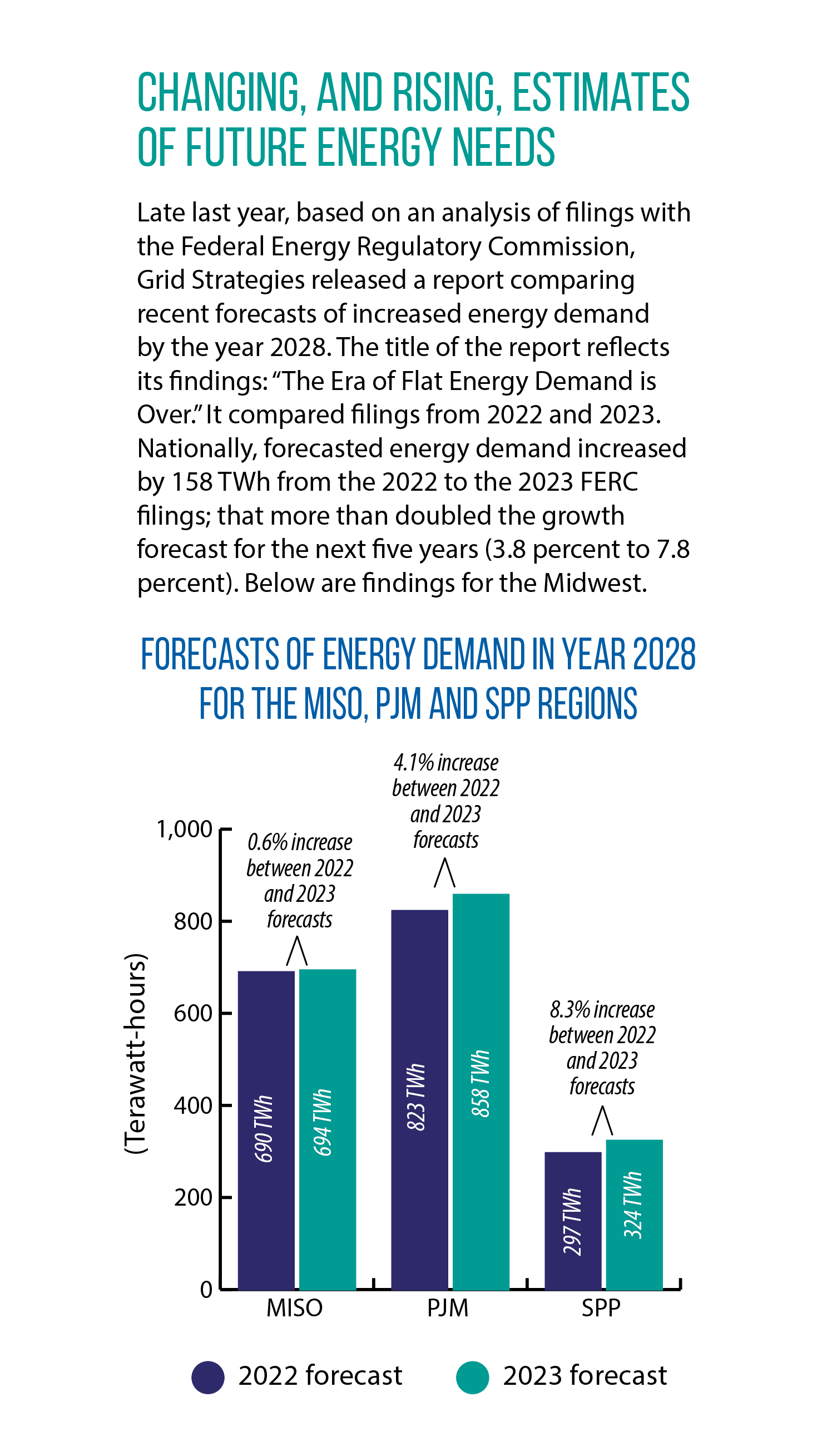

First, unanticipated, rapid load growth has occurred due to a rise in electric vehicle fleets, an onshoring of industries, and the opening of many new energy-intensive data centers. Nationally, growth is about 1 percent annually, which doesn’t sound like much but is more than double what the demand increase has been, year over year, in recent history, he said.

Second, older generating plants have been retired. Third, these two trends are happening in a “carbon-constrained environment,” the result of state and federal policy choices or corporate buying practices/preferences.

Lastly, Clark said, “There’s no silver bullet that will replace that much capacity in a short amount of time that’s carbon-free.”

With that setup, Clark asked the session’s panelists — all leaders in the energy and electricity sectors — what they most want legislators to know about maintaining a reliable electric grid.

‘Know your commissioners’

One of their messages was to embrace the role, and opportunity, of bringing all stakeholders together to develop long-term outlooks and policy strategies. Few groups have the kind of convening power that state elected officials do.

Engage in conversations with your utilities and co-ops, and with all players in this field because they must be part of addressing the complex, difficult issues at play, said Maria Haberman, vice president of Ohio external affairs for American Electric Power and a former Ohio Senate staffer.

Todd Snitchler echoed some of these sentiments.

“If you don’t know your [public utility] commissioners, and you’re on committees with jurisdiction, you ought to know them,” and not just from their testimony in committees, but from meetings where you can learn about issues, said Snitchler, a former Ohio legislator and current president and CEO of the Electric Power Supply Association.

“Your state commissions typically have deep technical expertise, and those people want to help. They want to share the information they have so you can make better informed decisions.”

J. Arnold Quinn, senior vice president of regulatory policy at Texas-based Vistra Corp., and a former FERC staffer, urged lawmakers to resist calls to always “do something”; rash decisions, he said, can upset what markets may already be correcting.

For energy generators such as Vistra, Quinn said, projections of load growth look like a stable situation for long-term investments to meet that increased demand, but only if there is regulatory certainty.

“We don’t need a guarantee, we just need some sufficient level of confidence that the rules of the game are not going to change after we’ve made a big investment,” he said. “Just be mindful of how decisions you make affect those investment decisions.”

What customers want: Reliability

Snitchler highlighted two paramount issues for legislators to consider today, and for the foreseeable future.

There is enough power now for the U.S. economy, he said, but load growth is coming. Complicating matters are the unknowns about that growth; there are wide variations in the predictions about how much new generation will be needed and when.

“Reliability is now front and center,” said Snitchler, who also has served as a vice president of market development at the American Petroleum Institute and as a past chair of Ohio’s Public Utilities Commission and Power Siting Board.

Second, Snitchler said there is a “misalignment” between the aspirational goals of policymakers for cheap, low-carbon electricity and the operational realities of electric and natural gas systems.

The former is fine, but hard and fast deadlines create stresses on systems that are otherwise manageable, he said.

“All these policy decisions made at the state and federal levels have costs associated with them,” Snitchler said. “As market participants, we want to help achieve those outcomes. But in the end, if consumers can’t afford it, then they don’t support it.

“Consumers want three things: lights on, beer cold, water warm.”

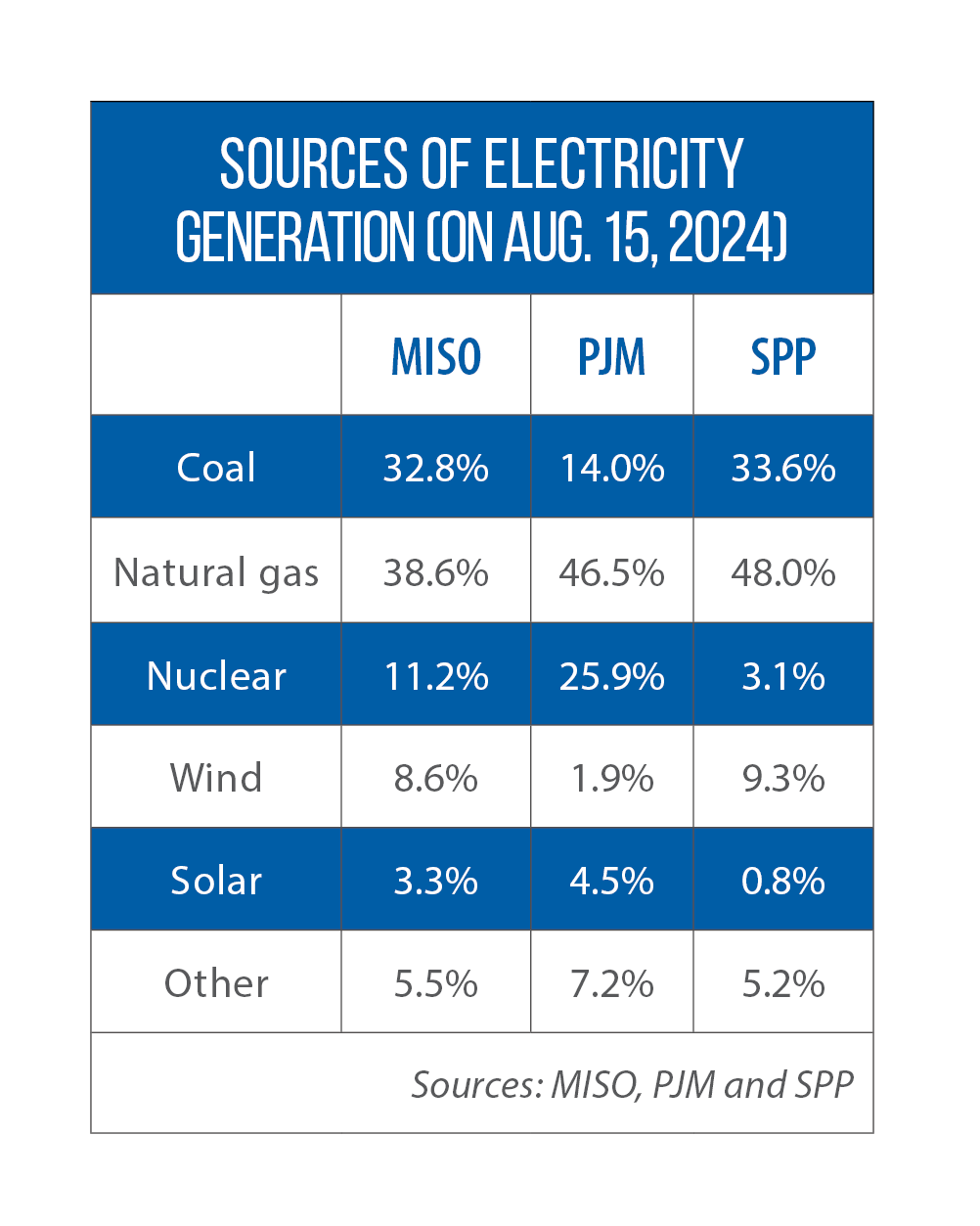

According to Chris Zeigler, executive director for API Ohio, a division of the American Petroleum Institute, and a former Ohio legislative and congressional aide, natural gas is and will be the best near-term option to accommodate growing demand — especially for facilities that rely on baseload electricity 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

Natural gas is the largest source, 43 percent of utility-grade electricity generation, and more is available, he said.

“There are challenges with natural gas, but we believe it can help us tackle load growth issues if the right policies are in place,” he added.