Great Lakes: Ohio, other Midwest states are investing more in water quality, exploring new ways to manage phosphorus

Ten years ago, toxins from harmful algal blooms in Lake Erie’s western basin left an entire Ohio city without safe water for several days.

One cause of the Toledo water crisis: phosphorus from farm fields and wastewater systems that reached Lake Erie’s western basin and its warming, shallow waters.

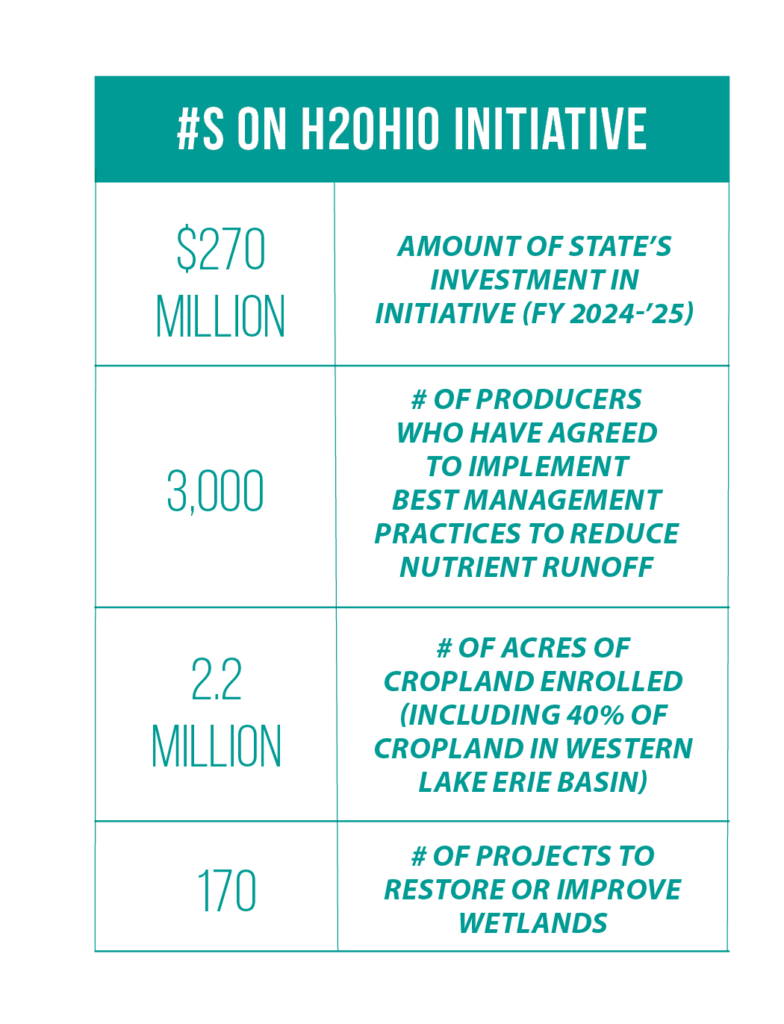

A decade later, 1.85 million acres of cropland in that basin has been voluntarily enrolled in a water quality initiative known as H2Ohio. With financial and technical assistance from the state and local Soil and Water Conservation Districts, enrolled farmers agree to adopt nutrient management plans and practices proven to reduce runoff.

At the Midwestern Legislative Conference Annual Meeting, an expert panel discussed the progress being made under H2Ohio, as well as whether voluntary programs like it are enough to protect the region’s water resources. Ohio Sen. Theresa Gavarone, who serves as Ohio’s representative on the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Legislative Caucus Executive Committee, introduced the session. Great Lakes Commission executive director Erika Jensen moderated the discussion.

‘All of the above’ approach

In 2015, Ohio, Michigan and Ontario agreed to reduce phosphorus inputs into Lake Erie by 40 percent by 2025. For Ohio to reach that goal, whether in 2025 or beyond, many more acres of farmland in the western basin will need to be enrolled in H2Ohio. The current number, 1.85 million acres, represents about 40 percent of the total. Joy Mulinex, director of the Ohio Lake Erie Commission, said enrollment of between 65 and 75 percent of farm acreage in the basin is needed to reach the phosphorus reduction goal. The state is pursuing several other strategies as well.

“H2Ohio has been an all-of-the-above approach,” Mulinex told MLC attendees.

Through the initiative, Ohio is replacing private septic systems, restoring and improving wetlands, and investing in pilot projects that use new technologies to reduce and remove phosphorus. (Ohio also is paying for the removal of lead service lines through the program.)

H2Ohio began in 2019 and is coordinated by three state entities: the Environmental Protection Agency and the departments of Natural Resources and Agriculture. The General Assembly appropriated $270 million for H2Ohio in the most recent biennial budget.

Beyond Ohio and the Great Lakes region, other programs and partnerships with producers are being implemented.

“It is in our economic, ecological, and social best interest to reduce nutrients in our waterways,” said Kirsten Wallace, executive director of the Upper Mississippi River Basin Association, whose member states are Iowa, Illinois, Minnesota, Missouri and Wisconsin.

According to Wallace, there are signs of progress on water quality. The amount of suspended sediment in the river has fallen, thanks in part to improvements in wastewater treatment and the adoption of effective edge-of-field farm practices.

Wallace also highlighted the promise of a “batch and build” model first started in Iowa’s Polk County. With a mix of local, state and federal funds, conservation projects now move forward on multiple agricultural lands at once. The result in Iowa has been a simplified process for producers, and a much larger number of farm fields that have installed bioreactors and saturated buffers, both of which reduce runoff.

Still, Dan Egan, author of “The Devil’s Element: Phosphorus and a World out of Balance,” stressed that more action is needed to reach reduction goals and improve the health of water systems.

He called for regulations that would restrict the size of concentrated animal feeding operations. These CAFOs, Egan said, continue to be a major source of nutrient runoff because of the manure produced on them. He also pointed out a potential opportunity for policymakers: find ways of turning a pollutant into a domestic food security tool.

According to Egan, domestic sources of phosphorus (vital to agriculture production) are due to run out in the next 40 years. One solution is to invest in technologies that reclaim and more efficiently use it.

“We’re already starting to manage [phosphorus] differently,” he said. “In Wisconsin, they’ve implemented a program where the biggest of the dairies are installing digesters to strip the methane out of the manure … and we can not only take out the methane, we can take out the nutrients [polluting waterways].”