Transforming maternal care: State-based reforms in Ohio include use of value-based payment model

One obstetrical practice in Ohio recently opened a “fourth trimester” clinic to meet the needs of new mothers — for example, support for postpartum depression or help with breastfeeding.

In another practice, group-based pregnancy education services now operate under an “opt out” model: all expectant mothers in the practice are presumed to want and get these additional prenatal care and social supports, unless they say otherwise.

Other providers have begun hiring lactation specialists, behavioral health counselors or other staff.

Driving these types of innovations is a new payment model known as Comprehensive Maternal Care, an initiative within Ohio’s Medicaid program to incentivize quality care, address infant and maternal mortality and morbidity, and reduce health disparities.

“It’s pretty phenomenal how well they’re doing after just one year [of the program],” Ohio Medicaid Director Maureen Corcoran said about advances being made by the participating practices. Corcoran made her remarks as part of a July presentation at the Midwestern Legislative Conference Annual Meeting.

Led by the MLC Health and Human Services Committee, the session focused on how states and their legislators can improve outcomes for mothers and infants.

“Your lever is Medicaid,” said Sinsi Hernández-Cancio, vice president for health justice at the National Partnership for Women & Families, who joined Corcoran as a featured presenter.

“Your lever is Medicaid,” said Sinsi Hernández-Cancio, vice president for health justice at the National Partnership for Women & Families, who joined Corcoran as a featured presenter.

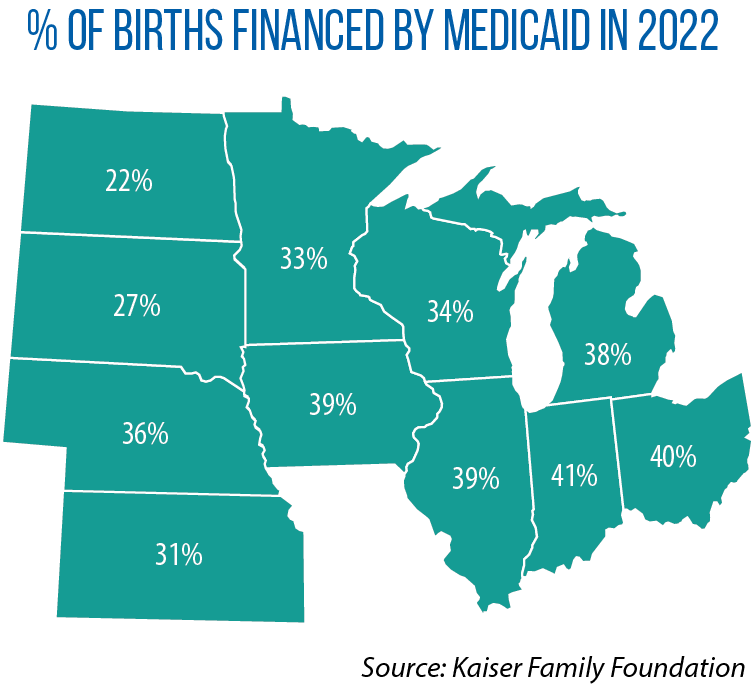

That is because the public health insurance program for low-income families is such a large payer of maternal care; in 2022, it financed one-third or more of births in most Midwestern states.

Medicaid is the largest such payer in Ohio, and the state has embarked on a series of reforms since the passage of SB 332, a bill from 2017 that established new goals and policies to reduce infant mortality.

Comprehensive Maternal Care is one of Ohio’s newest policy reforms. According to Corcoran, 137 practices already are enrolled (the program launched in 2023) and eligible for an additional value-based payment via the state’ s managed-care system for Medicaid. The monthly payment is $15 for each low-risk pregnancy, $40 for each high-risk pregnancy. For even a smaller practice with 200 lower-risk and 150 higher-risk deliveries a year, that adds up to $80,000 a year, Corcoran noted.

Ohio also has made other changes in Medicaid-based maternal care over the past five years. It has begun to cover nurse home visiting and group prenatal care; extended postpartum coverage to 12 months; expanded coverage for lactation counseling; and targeted investments in community-based services in the counties and neighborhoods with the highest rates of infant mortality.

One of the most important advances, Corcoran said, has been working with the state’s managed-care and maternal-care providers on a reporting system that ensures the health system can reach expectant mothers early in their pregnancy and connect them to services.

At the federal level, Hernández-Cancio said, a new 10-year Transforming Maternal Health Initiative has opened up a new funding opportunity for states. To qualify for the grant program, states must adopt a series of policies to improve care for expectant and new mothers. That includes development of a value-based payment model such as Ohio’s.