MLC Chair’s Initiative on Workforce | State-led strategies to get most out of investments, build pathways to career success

Every year, $4 billion or more flows from the federal government to states for workforce training and development. Add to that the billions of dollars being invested over the next five years in local economies under laws such as the CHIPS and Science Act, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and the Inflation Reduction Act, and states are positioned to think big about workforce innovation and transformation.

But an expert panel at this summer’s CSG Midwestern Legislative Conference Annual Meeting also had a note of caution for the region’s legislators: Make your state’s approach to workforce policy more strategic, nimble and holistic, or you risk wasting those taxpayer dollars as well as some of the coming economic opportunities.

“In a place like Ohio, and I imagine in many of the states represented here, we’re a little hungry, right?” Ohio Lt. Gov. Jon Husted said to legislators during the session. “We went through three decades of being kicked around pretty good because our manufacturing base got eroded, and generations of people moved out of our states.

“In a place like Ohio, and I imagine in many of the states represented here, we’re a little hungry, right?” Ohio Lt. Gov. Jon Husted said to legislators during the session. “We went through three decades of being kicked around pretty good because our manufacturing base got eroded, and generations of people moved out of our states.

“And now that we’re doing ‘made in America’ again, we’re developing supply chains again, we have the opportunity to help the people in our communities, the businesses that are there, capture this moment.”

It’s a time of “more people than jobs,” he added, and where a skilled workforce will top the list of factors for businesses on where they invest and locate.

Joining Husted on the expert panel were Shalin Jyotishi of New America and Jeannine LaPrad of the National Skills Coalition. Pat Tiberi, a former state legislator, U.S. congressman and now head of the Ohio Business Roundtable, moderated the discussion. The session was held in support of the 2024 MLC Chair’s Initiative of Ohio Sen. Bill Reineke: Workforce Innovation and Transformation.

How and why some job training fails to deliver

According to Jyotishi, the billions of dollars coming to states via federal laws such as the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) and the Perkins Career and Technical Education Act have not yielded the kind of results that policymakers should demand. In 2022, for example, a U.S. Department of Labor study found that in the first three years after individuals completed training under federally funded career pathways programs, their wages were only 6 percent higher compared to those who did not.

Further, the average wage of program completers was about $17,000 a year, and any positive earning effects of the training disappeared over the medium and long term.

“That doesn’t sound like a very effective outcome to me,” said Jyotishi, the founder and managing director of New America’s Future of Work and Innovation Economy Initiative. “Taxpayers lost, the workers lost, and, as we well know, employers still face workforce challenges.”

States have the authority to steer these programs in a different direction. Avoid “low-quality training” that leads to “unemployment, under-employment or employment in poverty-wage jobs,” Jyotishi said, and make sure funding lines up with your state’s broader economic needs and aspirations.

States have the authority to steer these programs in a different direction. Avoid “low-quality training” that leads to “unemployment, under-employment or employment in poverty-wage jobs,” Jyotishi said, and make sure funding lines up with your state’s broader economic needs and aspirations.

This requires more strategic thinking and planning on workforce policy, a role that legislatures can lead on.

“If you are looking to build your semiconductor industry, make sure your WIOA and Perkins funding is aligned to fund workforce programs in the semiconductor industry,” he said. “Trucking right now represents more of WIOA funds than the next nine categories of occupations. Trucking has a 90 percent turnover rate. Some of the jobs pay well, but it tends to be a very grueling occupation.

“And I haven’t seen a lot of legislators that want to grow the trucking industry as a strategic economic development priority.”

‘It has to be localized’

Husted, who leads the Ohio Governor’s Office of Workforce Transformation, cautioned about relying too heavily on federal workforce policy or funding (“it’s too slow and bureaucratic” to be a centerpiece of your strategy, he said) or trying to “central plan” at the state level.

“It has to be localized,” Husted said. “You can have goals, you can fund it, you can have expectations. But allow latitude for local delivery.”

“It has to be localized,” Husted said. “You can have goals, you can fund it, you can have expectations. But allow latitude for local delivery.”

Within every state, Husted noted, there are many distinct economic regions — in Ohio, for example, a strategy for Cincinnati might not be suited for Columbus, Akron, Dayton or rural areas.

“You have to have a private-public partnership where you understand the unique needs of the region that you’re in,” Husted said. “Your public institutions — your high schools, your career centers, your community colleges, your universities — need to be aligned with what’s happening there.”

This collaboration might only occur, though, with a nudge or incentives from the state.

“You get the educator sitting there at the table, you get the private sector sitting there, and you get them to agree on what they need,” Husted said. “And then you finance it.”

Ohio does this in part through its Industry Sector Partnerships initiative. Led by the business community, and including involvement by education and training providers, these partnerships develop and implement a workforce strategy, either for a single sector or multiple sectors, but always for a single region within the state.

Another policy trend has been to nurture more sector-based strategies.

In Michigan, for example, the state prioritizes select industry sectors (agriculture, health care, energy and information technology are among them) and brings together multiple employers from a single sector to determine its talent needs and challenges. Next, they work with local educators and others to develop a “demand-driven workforce system.”

“When I think of state policy as a lever to better align industry and academia and economic development … there’s no strategy that I think of as more important than sectoral strategies,” Jyotishi said.

More than training: Workers need ‘holistic supports’

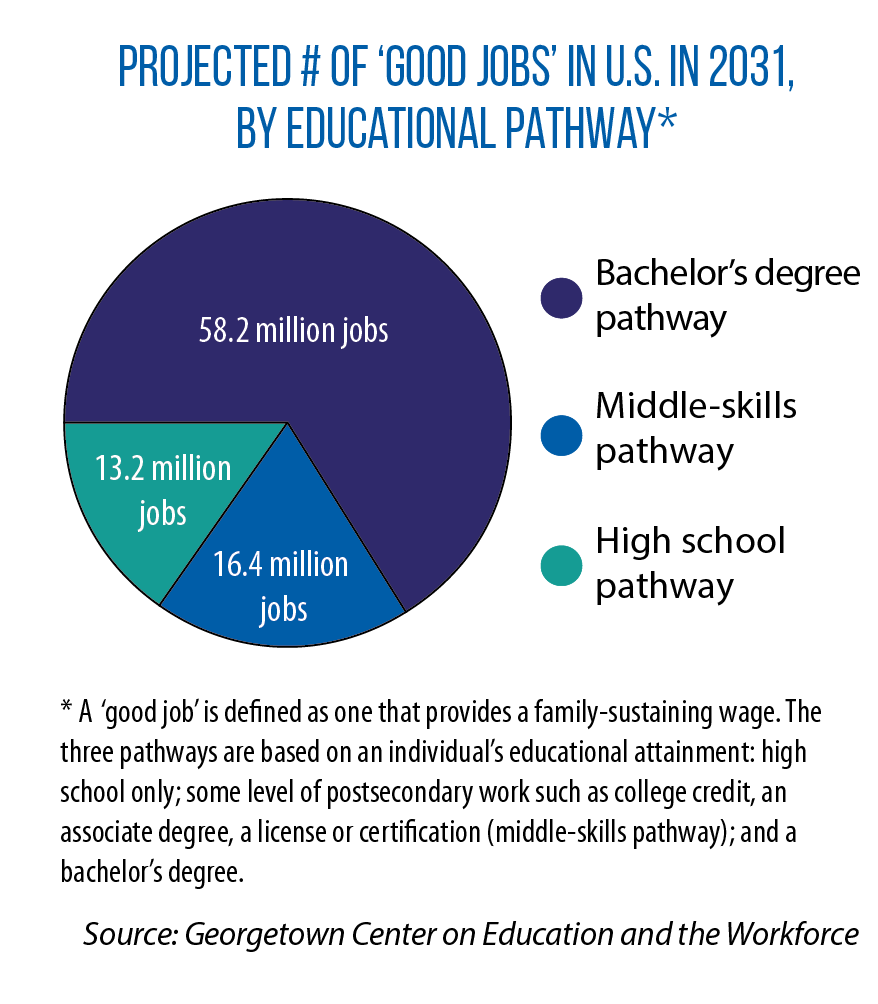

This recent era of “more jobs than people” is captured in data tracked by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics: the number of unemployed persons per job opening. Nationwide, the ratio was 0.8 as of June 2024, compared to 1.9 in 2014 and 2.1 in 2004. (Over the past two years, the number of unemployed persons per job opening has increased some, from a low of 0.5 in parts of 2022 to the July 2024 ratio of 0.8.)

In the Midwest, these ratios are even lower than the U.S. average in North Dakota and South Dakota (0.4), Minnesota (0.5), Nebraska and Wisconsin (0.6), and Iowa and Kansas (0.7).

In part because of this tight labor market, more attention is being paid to the barriers that stand in the way of people participating in job training, earning a postsecondary credential or degree, and entering and staying in the workforce.

“Many folks need access to holistic supports and services,” said LaPrad, managing director of policy and research at the National Skills Coalition.

Addressing concerns about the costs of child care, for instance, has become more central to state workforce strategies, with LaPrad singling out Iowa and Michigan as examples. In Iowa, state incentives are now available to businesses that offer child care as part of their benefits packages for workers, and in Michigan, an innovative “tri-share” model shares the costs of child care equally among the employer, the employee and the state.

“We’re going to see a need to focus not only on child care, but elder care and other family-care issues are also becoming fundamental for many workers,” LaPrad added.

Apprenticeships in reach for high school students

Husted has been working on workforce policy for several decades, including periods marked by “more people than jobs.” Today, he said, business leaders are eager to be part of building a skilled workforce, which requires partnerships with state education systems, both K-12 and postsecondary.

At the K-12 level, Husted noted, every school district in Ohio must now have a business advisory council, a convening of local education and business leaders to foster work-based learning opportunities centered on the area’s economic drivers. The state also is placing a greater emphasis on career and technical education, as reflected in a renamed and reorganized state Department of Education and Workforce (SB 1 of 2023) and a two-year state budget that included $267.7 million in grants to expand the capacity of CTE programs.

At one Ohio career center, Husted noted during the session, 96 percent of graduates had job offers and, as a class, had earned $2.5 million while still in school thanks to apprenticeships at local businesses.

“They were leaving as electricians, robotics maintenance technicians and nurses, and with a variety of different skills,” Husted said.

His goal is that all Ohio high school students graduate with a “skill that is hireable and desired in the economy, because from there, they can either go directly to work or go to work somewhere where the employer will pay for their college degree.”

According to Jyotishi, youth apprenticeships are a promising model for states, particularly those that offer students the chance not only to “earn and learn” in high school, but also accrue college credits prior to graduation. He pointed to Career Launch in Chicago and Kalamazoo, Mich., and the Learn and Earn to Achieve Potential (LEAP) initiative in Minneapolis as exemplary programs.

According to Jyotishi, youth apprenticeships are a promising model for states, particularly those that offer students the chance not only to “earn and learn” in high school, but also accrue college credits prior to graduation. He pointed to Career Launch in Chicago and Kalamazoo, Mich., and the Learn and Earn to Achieve Potential (LEAP) initiative in Minneapolis as exemplary programs.

Wisconsin has the oldest and largest youth apprenticeship program in the nation, the Urban Institute noted in a 2023 study, and the Legislature has since increased state support for it, up to a total of $19 million in the current two-year budget (compared to $12 million in the last biennium.). Local coalitions of school districts, labor organizations and industry groups run each of Wisconsin’s youth apprenticeships, which focus on training and learning in a “career cluster” identified by the Legislature in statute.

Outcome-based funding for community colleges

At the postsecondary level, LaPrad said, a handful of states are moving toward performance-based funding for community colleges. She noted a new law in Texas as an example. Under HB 8 of 2023, student outcomes will determine funding levels. One of the metrics that will be used: the number of college students who earned a “credential of value,” with extra weight given to credentials tied to a high-demand occupation. Additionally, to have “value,” the credential must be tied to eventual future higher earnings for the student.

“Refinancing should be foundational to how we think about public institutions, especially two-year institutions, being able to be more nimble,” LaPrad said, noting how the incentive structure rewards colleges that adapt to evolving workforce needs.

“Refinancing should be foundational to how we think about public institutions, especially two-year institutions, being able to be more nimble,” LaPrad said, noting how the incentive structure rewards colleges that adapt to evolving workforce needs.

The panel also explored changes coming from technological advances such as the rise of artificial intelligence, which they said, at first, is likely to augment rather than replace jobs.

In Ohio, Husted said, the state’s TechCred program now offers reimbursements to employers for the costs associated with a worker earning an industry-recognized, technology-focused credential. The reimbursement is up to $2,000 per credential. As of May 2024, more than 100,000 credentials had been awarded, and AI-based credentials are making up a larger and larger number of requests, Husted said.

Jyotishi suggested public investments in programs that embed industry certifications into postsecondary programs that also lead to degrees.

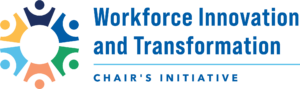

“Degree programs are still going to be important if you want the tech jobs and if you want this region to become the Tech Belt, not the Rust Belt,” he said.

Workforce Innovation and Transformation is the CSG Midwestern Legislative Conference 2024 Chair’s Initiative of Ohio Sen. Bill Reineke.