Laws in states such as Minnesota, along with a new federal drinking water standard, mark latest efforts to end threat of ‘forever chemicals’

The class of “forever chemicals” known by the acronym PFAS is the focus of a new federal drinking water standard as well as a wave of recent state legislation calling for partial or comprehensive bans on their use in commercial products.

Minnesota is in that vanguard of states.

In 2023, it became the third U.S. state, and first in the Midwest, to enact a phased ban on the manufacture and sale of commercial products containing “intentionally added” PFAS. Maine and Washington were the first two states with comprehensive bans — under laws from 2021 and 2022, respectively.

Such prohibitions are the latest state legislative development on PFAS reflecting a growing attempt to undo a Gordian knot almost a century in the tying.

Invented in the 1930s, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances feature a very strong molecular bond between fluorine and carbon that both repels water and oils and doesn’t break down over time.

Those two qualities are the reason PFAS became so commonplace in packaging, clothing, firefighting foams, and a host of household products (carpeting, cookware, cosmetics and dental floss, among many others). These chemicals also have myriad medical and industrial uses.

But as a 2021 study from the National Institutes of Health notes, concerns began to be raised at the turn of this century about the impacts of these “forever chemicals” — their presence in soil and waterways, their tendency to accumulate in organisms, and their possible toxicity in humans.

Minnesota ban begins to take effect in 2025

Bill Kramer, vice president of the public policy consultancy firm MultiState, says state legislatures began focusing on PFAS last decade.

Among the first wave of legislative responses: ban PFAS-containing firefighting foams, require testing of drinking water, and set maximum contaminant levels (a legally enforceable standard) in drinking water and groundwater.

In the Midwest, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio and Wisconsin restricted the use of firefighting foams with intentionally added PFAS for training or testing purposes. Illinois, which also bans the incineration of PFAS, is phasing out foams with PFAS starting in 2025.

More recently, Kramer says, policymakers have focused on consumer products, as seen in two common strategies:

1) reporting requirements to identify products that contain intentionally added PFAS, and

2) outright bans on the use of PFAS in specific products or product categories, including packaging.

“[States] start with food containers and firefighting foam; those are two popular areas [for product-related bans],” Kramer says.

Less common are comprehensive PFAS prohibitions such as Minnesota’s.

Under HF 2310, the PFAS ban covers carpets or rugs, cleaning products, cookware, cosmetics, dental floss, fabric treatments, juvenile and menstruation products, textile furnishings, ski wax, and upholstered furniture.

The prohibition on these classes of products containing “intentionally added” PFAS takes effect in 2025. Seven years later, it expands to all products unless the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency determines PFAS use is “currently unavoidable.”

Starting in 2026, too, the manufacturers of products that contain intentionally added PFAS must submit reports to the state.

“We have a long way to go to get PFAS out of our daily lives, but this bill puts us on the right path,” Minnesota Rep. Jeff Brand, author of the original legislation, said after it became law.

The PFAS provisions in HF 2310 were dubbed Amara’s Law, named in honor of a woman whom Brand says died of a rare, terminal form of liver cancer caused by PFAS.

Another part of the Minnesota law bans the manufacture, sale and use of PFAS from certain firefighting foams as of this year, except at terminals and oil refineries. These facilities must phase out PFAS use by 2026.

Delays in Maine; review process in Washington

Maine’s 2021 law initially set 2030 as the target by which products with intentionally added PFAS would be banned from sale or manufacture. It also required manufacturers to report products for sale with intentionally added PFAS starting in 2023. The reporting deadline was delayed to 2025, however, because regulations weren’t ready in time.

Following negotiations between business and environmental groups to provide more time to comply with the law’s goals, Maine this year adopted significant changes: LD 1537 sets a longer phase-out schedule and changes language in the reporting requirement from “intentionally added” to “currently unavoidable use.”

Several products also are now exempt from the ban, including firefighting foam and medical devices or veterinary products regulated by federal agencies.

Washington’s 2022 law is different, Kramer says, because it authorizes the state Department of Ecology to create a regular process for determining “priority” chemical classes for review.

Part of that review is deciding whether to regulate those chemicals, and how, as well as identifying their presence in consumer products.

PFAS were among the first chemical class to be reviewed. Restrictions have since been proposed for aftermarket stain- and water-resistant treatments, carpets and rugs in 2025, and for indoor furniture in 2026.

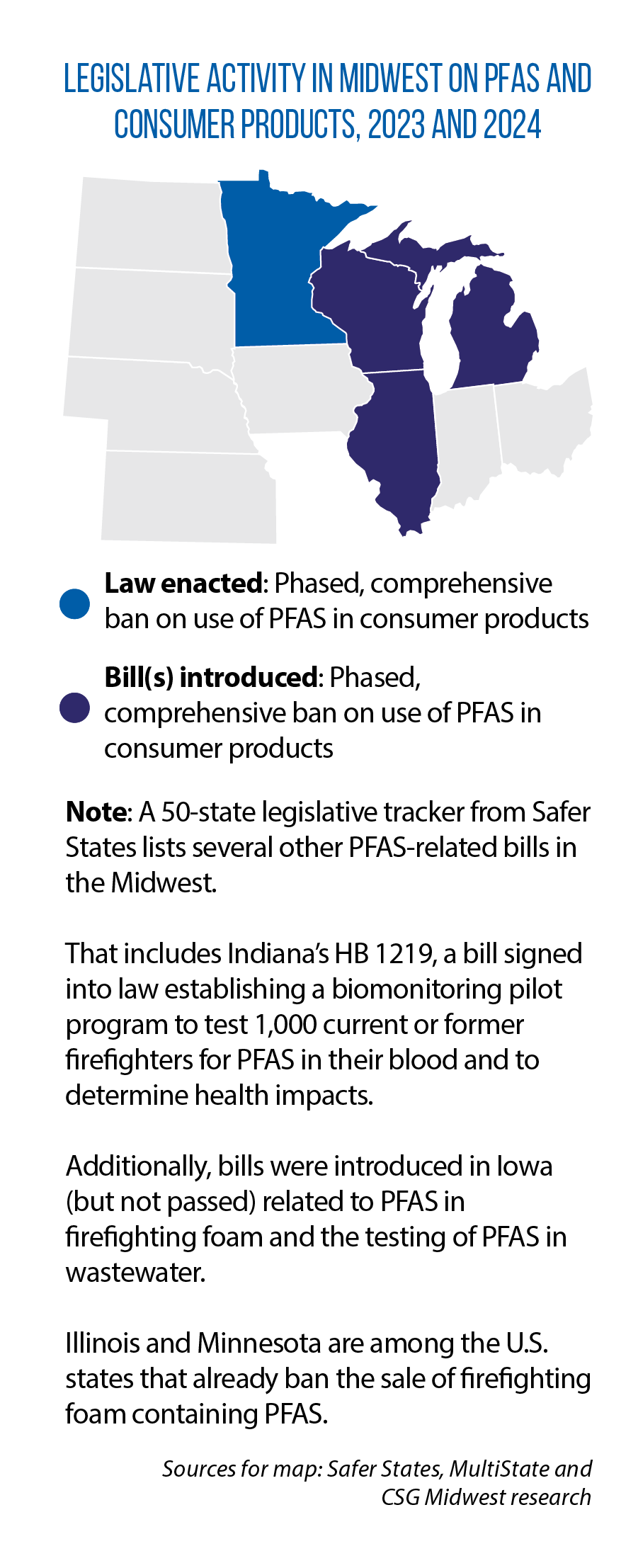

Activity in the Midwest

Will other states begin enacting comprehensive bans such as the ones in Minnesota, Maine and Washington?

In August, New Hampshire Gov. Chris Sununu signed into law a new PFAS ban. Legislation was also under consideration in at least three Midwestern states this year, but none of the bills had advanced past the committee stage as of September. (Sessions in Illinois and Wisconsin have ended.)

- Illinois’ SB 88 calls for a phased ban to begin taking effect in 2025.

- Michigan’s HB 5657 would ban the use of “intentionally added” PFAS in all household products by 2027, minus a determination that the use of PFAS is “currently unavoidable.”

- AB 1194/SB 1093 in Wisconsin would ban “intentionally added” PFAS from food packaging, cleaning products, cosmetics and textile furnishings by 2028, and from all products by 2034. There would be exemptions for “unavoidable use.”

Illinois SB 3360 is part of the other recent legislative trend noted by Kramer: a push for more reporting and understanding of what products contain PFAS. The measure would authorize Illinois’ participation in an interstate safe-chemicals clearinghouse, and products with intentionally added PFAS would need to be registered with the state.

“That would at least allow the ability to know who is adding PFAS to their products,” says the bill’s sponsor, Illinois Sen. Laura Ellman. “Right now, nobody really knows.”

EPA sets new standards

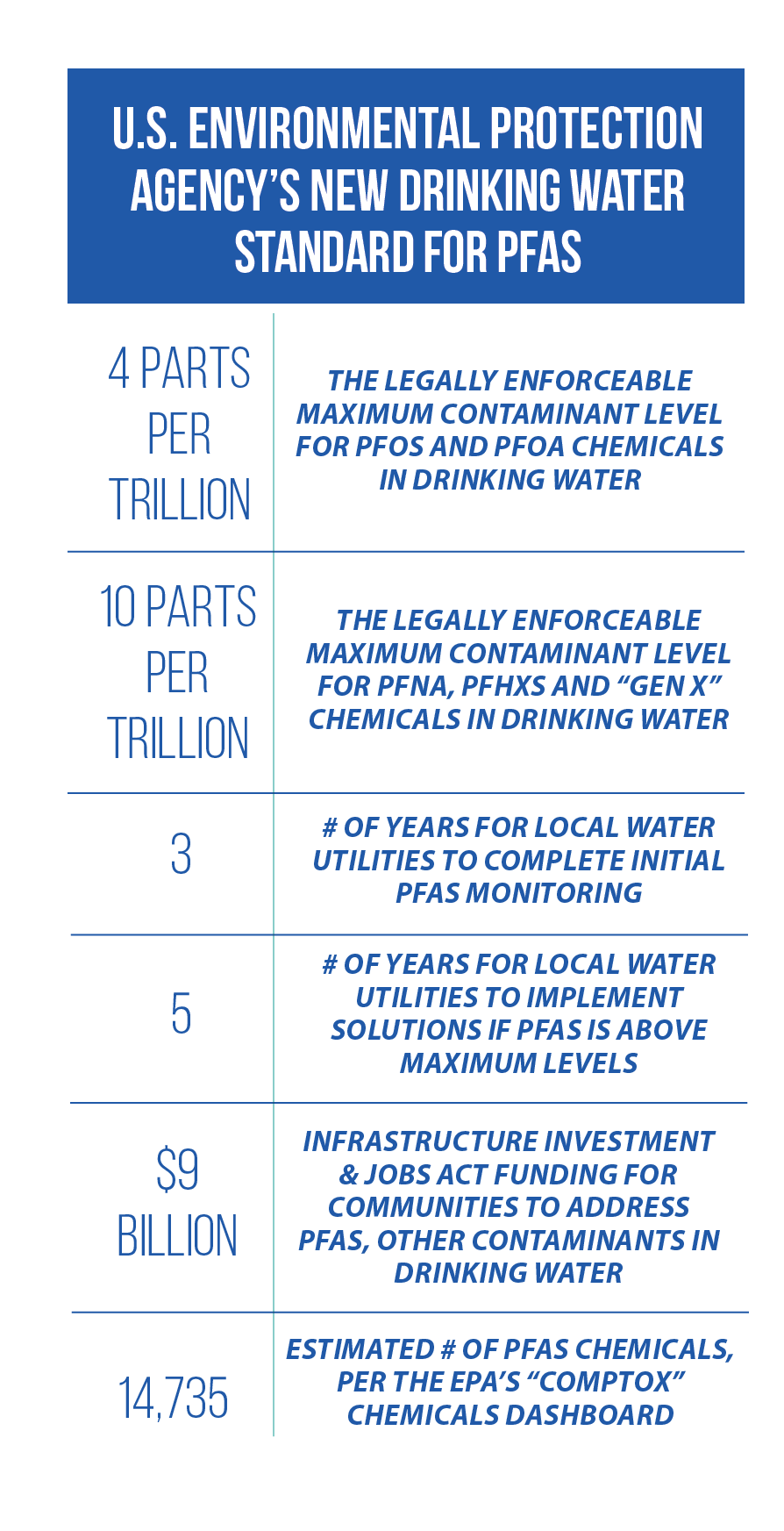

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in April released new national standards for PFAS in drinking water and designated two PFAS (PFOA and PFOS) as hazardous substances under the federal “Superfund” law.

This designation means that leaks, spills and other releases of PFOA and PFOS must be reported to the EPA. Sellers of contaminated property must now both disclose the contamination and guarantee it’s been cleaned up or will be in the future. The drinking water standard will require PFAS monitoring, and potential remediation, by local water utilities (see table for details).