States take multipronged approach to medical debt: prevent it, erase it or help those struggling to pay outstanding medical bills

Over the course of her 20-plus years as a registered nurse, Liz Boldon says she has cared for countless patients with more than just a health recovery on their minds.

They also worry about economic well-being.

“You hope they can be focused on healing and rest and getting well,” she says, “but you also see how they and their families get overwhelmed and preoccupied with the bills that are coming. And that concern about costs can impact the choices they make about care.”

Her experiences as a nurse inform Boldon’s work as a Minnesota legislator, including efforts to reshape laws in a way that provide relief for individuals who find themselves in medical debt.

Her experiences as a nurse inform Boldon’s work as a Minnesota legislator, including efforts to reshape laws in a way that provide relief for individuals who find themselves in medical debt.

Most recently, she served as a chief author of Minnesota’s Debt Fairness Act, a wide-ranging new law (part of the omnibus SF 4097) that took effect in October. Among the many statutory changes: banning medical debt from being reported to credit bureaus; preventing providers from withholding medically necessary care due to unpaid bills; and ending the automatic transfer of medical debt to a patient’s spouse (a creditor retains a claim against a decedent’s estate).

The act also extends wage garnishment protections and establishes new income-based garnishment levels. Under previous law, garnishment was capped at a flat rate of 25 percent of a person’s wages. Now, the limit may be as low as 10 percent for individuals with lower earnings.

“Medical debt isn’t like other debt,” Sen. Boldon says. “It’s not something you choose. It’s something that happens to you, oftentimes unexpectedly.”

She adds that the new law in Minnesota seeks to strike a balance. On the one hand, provide relief for those who need it; on the other, recognize that individuals should pay their debts and that medical providers should get what they are owed.

She adds that the new law in Minnesota seeks to strike a balance. On the one hand, provide relief for those who need it; on the other, recognize that individuals should pay their debts and that medical providers should get what they are owed.

She notes as an example Minnesota’s new prohibition on withholding medically necessary care. As a condition of providing treatment, providers can require patients to enroll in a payment plan for any outstanding medical debt.

According to Boldon, the final bill was the result of many hours of collaboration and negotiation; during the months of legislative session, a full room of stakeholders would often meet on early Monday and Friday mornings to resolve disagreements.

“There was some push on our part, certainly, but it was carefully negotiated, and we landed in a place that I would say everybody is OK with,” she says.

‘Pennies on the dollar’

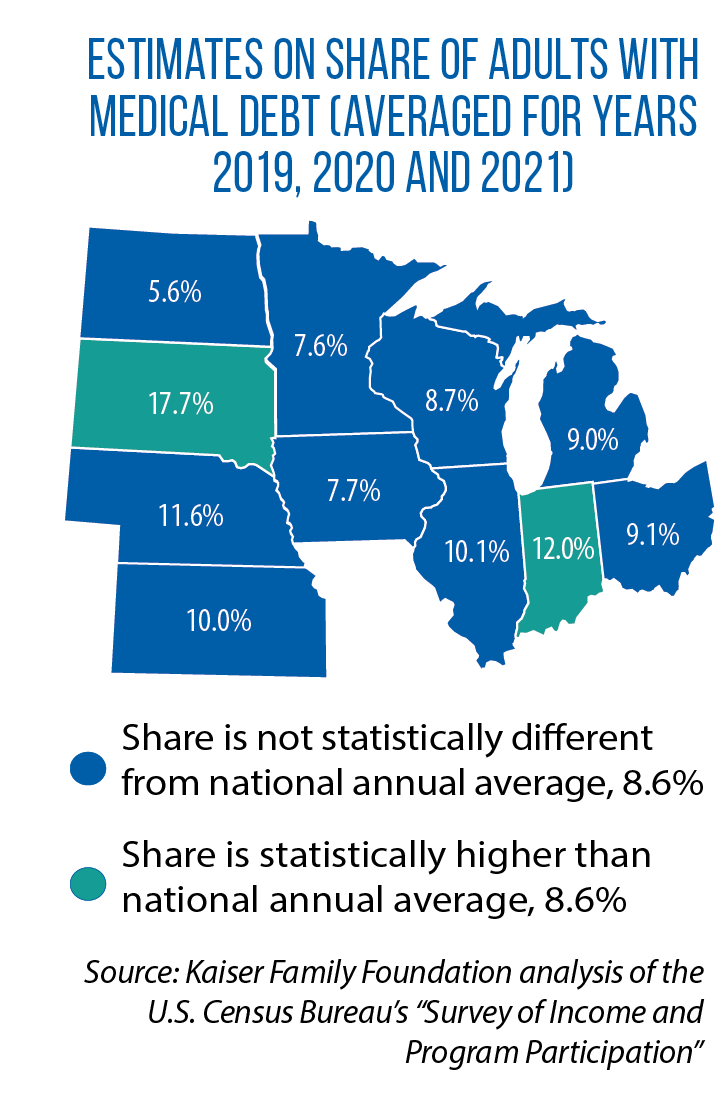

Minnesota is one of several U.S. states with new laws on medical debt. Other examples from the Midwest this year include Illinois (HB 5290) and Michigan (HB 4437, a state budget bill) dedicating state funds for programs to erase some residents’ medical debt.

The Illinois expenditure is $10 million, and lawmakers there say it will erase about $1 billion in debt. Michigan is spending $4.5 million and the amount of relief is estimated at $450 million.

The Illinois expenditure is $10 million, and lawmakers there say it will erase about $1 billion in debt. Michigan is spending $4.5 million and the amount of relief is estimated at $450 million.

“Over time, the value of the medical debt that [providers] hold goes down, so if it’s not been paid off in a couple of years, it’s kind of just this portfolio of debt that they’re holding. They’re not getting any money off of it,” says Maanasa Kona, explaining why these “pennies on the dollar” purchases of the debt can be made.

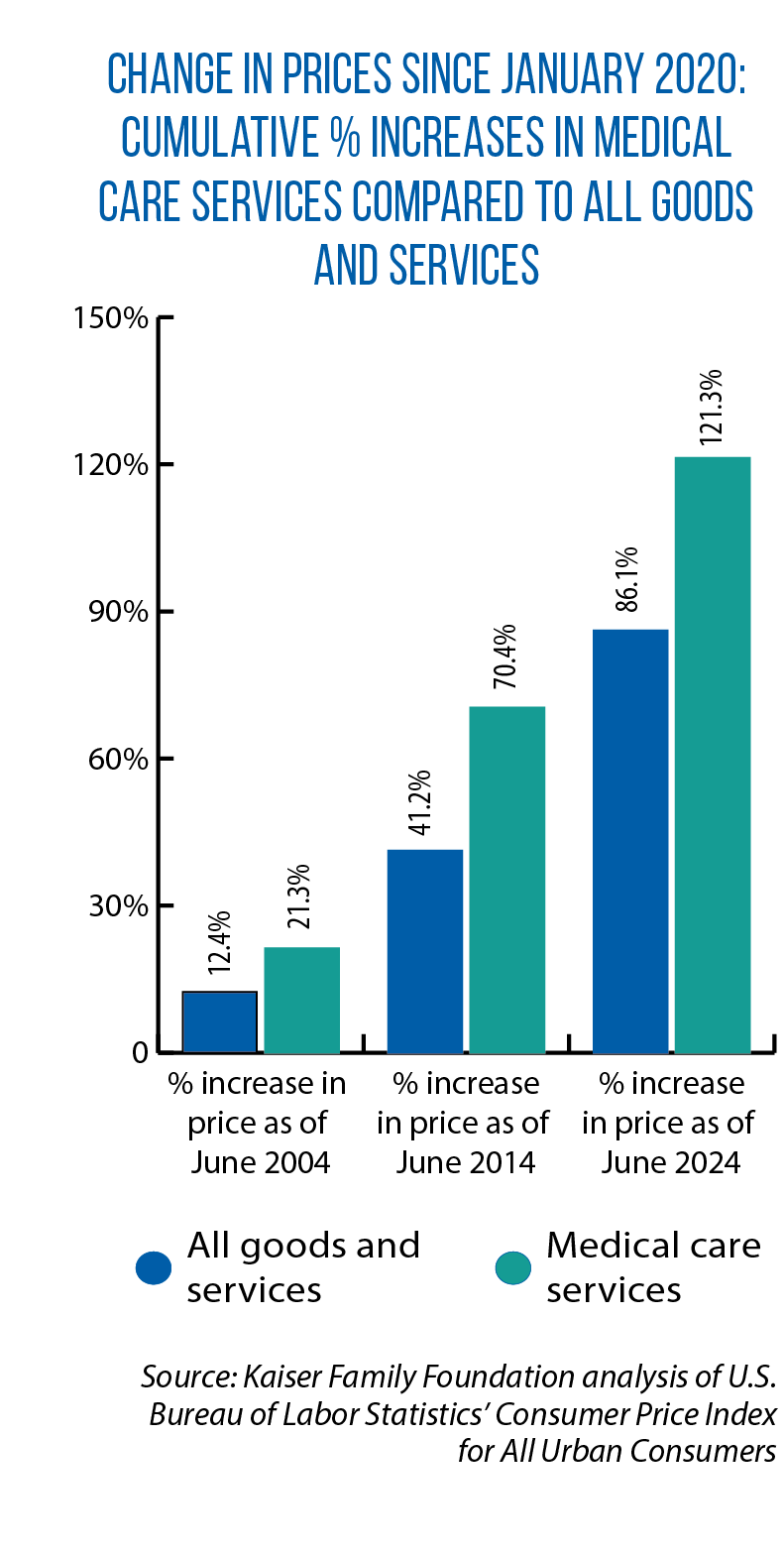

Kona, an assistant research professor at the Georgetown University Health Policy Institute’s Center on Health Insurance Reforms, says the recent spike in legislative activity on medical debt is the result of a “perfect storm” in the health care marketplace. Rising costs of medical services are colliding with increased cost-sharing demands on consumers.

“We’ve seen increases in deductibles, copays and patient responsibilities the last few years,” Kona says. “So you’re just seeing more cases of medical debt, especially among people who are insured and who theoretically should not be facing something like this.”

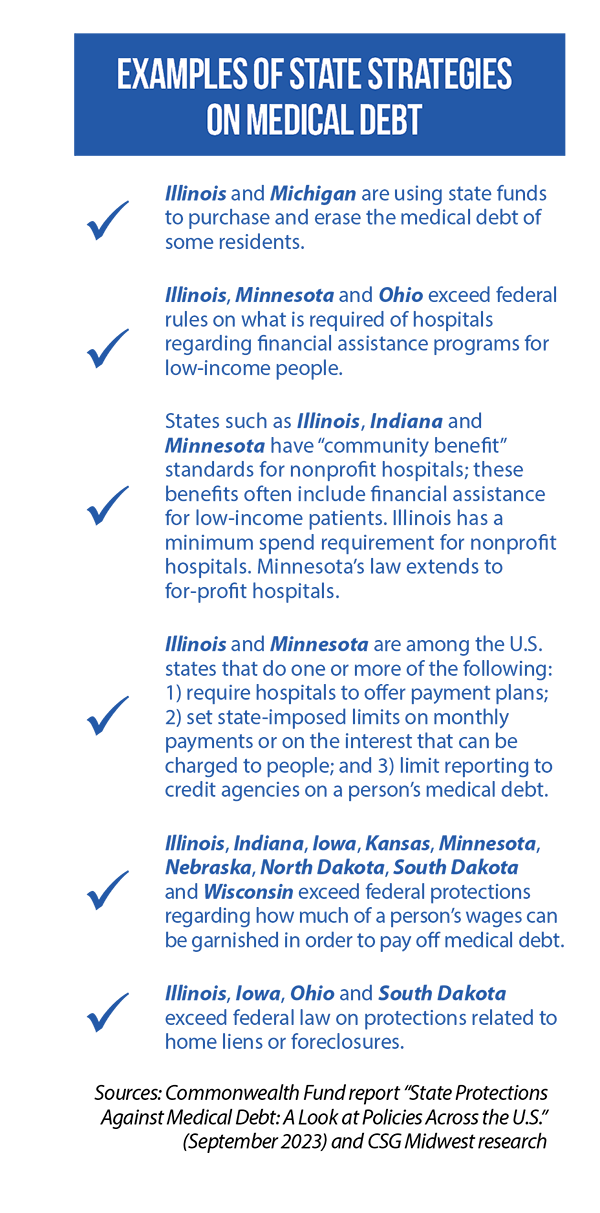

A February 2024 study from the Kaiser Family Foundation details the prevalence of medical debt. Researchers found that 6 percent of U.S. adults have more than $1,000 in medical debt and 1 percent more than $10,000. In all, an estimated 8 percent of adult Americans have some type of medical debt, usually $2,000 or more.

Kona says states have been pursuing a mix of new laws. Some measures seek to prevent individuals from going into medical debt in the first place, others help those already in it (see sidebar checklist for examples).

“Generally speaking, the more systemic and upstream the solutions are, the more likely you are going to create long-term, sustainable change,” she says.

One “upstream” policy lever for a state is to require more of hospitals and their financial assistance programs. First, establish statutory rules ensuring that lower-income individuals are eligible for free or discounted care. Second, make sure hospitals have a straightforward enrollment process.

One “upstream” policy lever for a state is to require more of hospitals and their financial assistance programs. First, establish statutory rules ensuring that lower-income individuals are eligible for free or discounted care. Second, make sure hospitals have a straightforward enrollment process.

Under a new Illinois law (HB 2719 of 2023), more patients will be automatically screened for eligibility, and hospitals must pursue cost-reducing options before taking collection actions against a patient.

According to a 2023 Commonwealth Fund study authored by Kona, other actions by states include limiting the interest that can be charged on medical debt, requiring hospitals to establish monthly payment plans (as an alternative to sending unpaid bills to debt collectors), and setting income-based limits on these plans.

‘Know what the price is’

Medical debt also has been part of the conversation this year in Ohio over transparency, or the current lack of it, in hospital pricing. Under HB 49, hospitals would be required to maintain a consumer-friendly, publicly available list of their charges for various non-emergency services.

Ohio Rep. Ron Ferguson, a primary sponsor of the bill, says a federal rule on hospital pricing transparency has lacked enforcement and compliance.

Ohio Rep. Ron Ferguson, a primary sponsor of the bill, says a federal rule on hospital pricing transparency has lacked enforcement and compliance.

States, he believes, can fill the void.

“In order to breed competition, we need to know what the price of something is,” Ferguson says. And under the House-passed version of HB 49, hospitals could not collect on medical debt unless they are in compliance with the state-level transparency rules.

“Obviously, people can’t do price shopping in emergencies,” Ferguson says. “But when you are in a situation where you can actually do some price shopping, certainly you’re going to be in less debt if you’re paying a cheaper price.

“And sometimes people end up getting billed for things that they weren’t really fully aware were part of a process or a procedure.”

The Senate passed a different version of HB 49 in June 2024. Among the differences was removal of the language on medical debt collection. According to Ferguson, the biggest point of disagreement is that the Senate version would allow hospitals to publish estimates, rather than actual prices.