Big data centers, big rewards for states?

As the number of these centers grows, states are offering new or enhanced tax incentives, but questions also are being raised about the demands on water resources and electricity

A central part of much of the modern economy, data centers are proliferating across the Midwest, offering economic opportunities while possibly placing increasingly heavy burdens on states’ water resources and electrical load capacities. They house the computers and servers that store emails and texts, backup files, passwords, websites and streaming services along with anything and everything done online in “the cloud.” They also host artificial intelligence and “crypto-mining” programs (used to solve cryptographic problems or tasks to earn digital currency, such as Bitcoin).

Because they run 24 hours per day, data centers need a lot of uninterrupted electricity and constant cooling to keep from overheating — factors raising concerns these facilities may overburden already-stressed electrical distribution systems and water resources. Data centers are in a growth spurt currently driven by the rise in generative AI technology, according to The Synergy Group, a Nevada-based market analytics firm focused on the tech sector. An April analysis notes the United States already hosts about half of the world’s more than 1,000 “hyperscale” centers, ones with at least 5,000 servers,10,000 square feet of space and 40 megawatts (MW) of capacity. That number is expected to double by 2028.

Because they run 24 hours per day, data centers need a lot of uninterrupted electricity and constant cooling to keep from overheating — factors raising concerns these facilities may overburden already-stressed electrical distribution systems and water resources. Data centers are in a growth spurt currently driven by the rise in generative AI technology, according to The Synergy Group, a Nevada-based market analytics firm focused on the tech sector. An April analysis notes the United States already hosts about half of the world’s more than 1,000 “hyperscale” centers, ones with at least 5,000 servers,10,000 square feet of space and 40 megawatts (MW) of capacity. That number is expected to double by 2028.

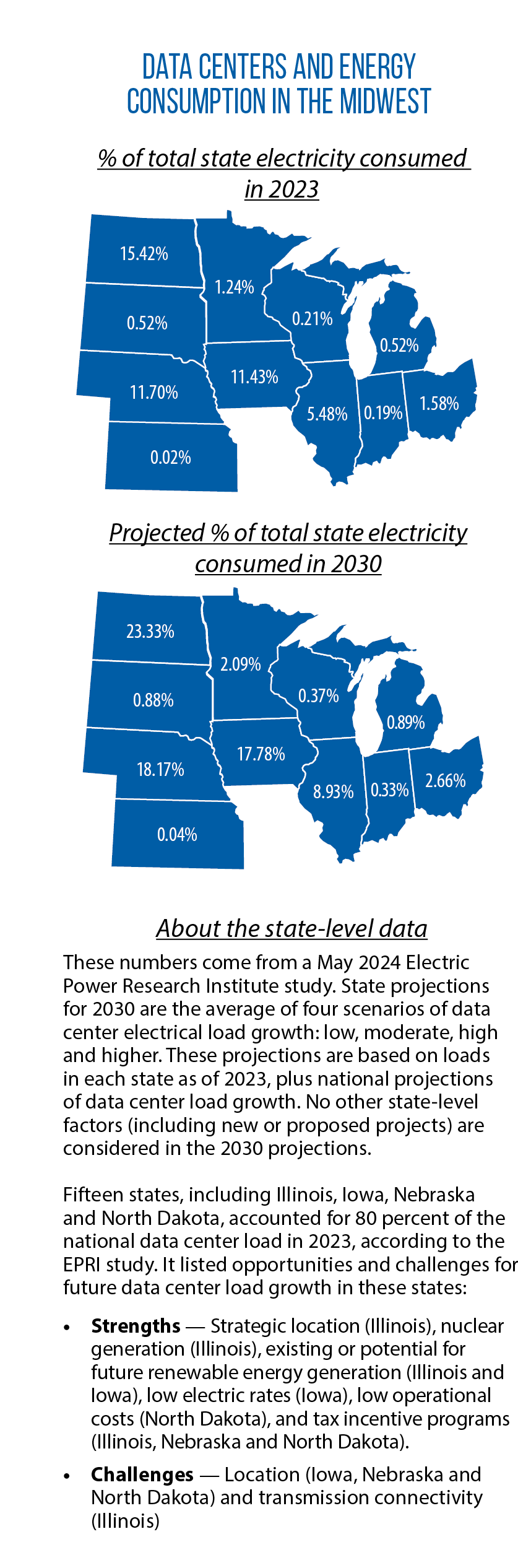

A June 2024 report by S&P Global also notes this rise in data centers and estimates how the numbers and power capacity of data centers in four Midwestern metropolitan regions will rise by 2028:

- In Chicago, an increase in the number of data centers from 66 to 122, and from 997 MW of capacity to 1,839 MW.

- In Columbus, Ohio, an increase in the number of data centers from 40 to 85, and from 914 MW of capacity to 1,627 MW.

- In Des Moines, Iowa, an increase in the number of data centers from 27 to 48, and from 712 MW of capacity to 1,286 MW.

- In Omaha, Neb., an increase in the number of data centers from 38 to 46, and from 1,233 MW of capacity to 1,798 MW.

The U.S. Energy Information Agency in June noted that North Dakota saw the fastest relative growth in commercial electricity consumption, up 2.6 million MW, or 37 percent, from 2019 to 2023. The EIA attributed this steep increase in North Dakota to the rise of data centers in the state.

‘Infrastructure of future’

Most Midwestern states offer tax incentives specific to data centers, typically some mix of sales and/or personal property tax exemptions (see state-by-state listing below). As part of these laws, states often require a minimum capital investment; some also set benchmarks on the number of new jobs being created and the wages being paid.

In Michigan, legislators in 2015 enacted a sales/use tax exemption on equipment for smaller-scale “co-located” data centers (ones that lease capacity to other companies). Measures introduced this year, HB 4906 and SB 237, would extend the exemption to larger-scale enterprise data centers. These new exemptions would last through 2050, or through 2065 for centers built on qualifying “brownfield” industrial sites or former power plants.

In Michigan, legislators in 2015 enacted a sales/use tax exemption on equipment for smaller-scale “co-located” data centers (ones that lease capacity to other companies). Measures introduced this year, HB 4906 and SB 237, would extend the exemption to larger-scale enterprise data centers. These new exemptions would last through 2050, or through 2065 for centers built on qualifying “brownfield” industrial sites or former power plants.

“There are a lot of knowledge-economy and tech-based industries that like to be close to data centers,” says Rep. Joey Andrews, sponsor of HB 4906. “You get one of these, you’re going to start seeing other associated industries move into the area around them. You start to be able to build that tech sector and knowledge economy base.”

Andrews envisions this kind of increased economic activity and tax base as being transformative for his district along the Lake Michigan shoreline. According to Andrews, a $3 billion data center project proposed in the city of Benton Harbor would double property tax revenue to local school districts and governments, and ease high unemployment with construction jobs. Under the legislation, projects would have to invest at least $250 million and create at least 30 new jobs, offering an annual wage at or above 150 percent of the median wage of the region in which they’re located.

The Michigan bills also echo some other states’ requirements that qualifying data centers have their buildings be certified under one or more national or international green building standards. When crafting HB 4906, Andrews says, attention was given to the existing data center laws and incentives in other states (particularly Michigan’s neighbors) that are vying to be hubs of what he calls “the infrastructure of the future.”

“Everything is going to run through this sort of technology,” he adds.

Data centers: Need for power

Do utilities and state utility regulators need to do more to account for the large amount of electricity required to operate these data centers? Energy leaders in Ohio have been mulling this question.

In March 2023, AEP Ohio, which provides power to 1.5 million customers in the state, declared a moratorium on new data center service agreements. At that time, the utility said it was already serving about 600 MW of data center load and had agreements to connect an additional 4.4 gigawatts (GW) by 2030, an amount that could be handled by the region’s transmission system. However, AEP Ohio also was facing potential demand for another 30 GW, which would require building more transmission infrastructure.

In March 2023, AEP Ohio, which provides power to 1.5 million customers in the state, declared a moratorium on new data center service agreements. At that time, the utility said it was already serving about 600 MW of data center load and had agreements to connect an additional 4.4 gigawatts (GW) by 2030, an amount that could be handled by the region’s transmission system. However, AEP Ohio also was facing potential demand for another 30 GW, which would require building more transmission infrastructure.

In 2024, AEP Ohio filed with the Public Utilities Commission tariff plans for data centers, one in May and then a revised version in October. The May 2024 proposal, for example, called for the data centers to make a monthly payment equal to 90 percent of the maximum amount of electricity they would need. A previous 60 percent demand charge was not sufficient, AEP Ohio said. The revised tariff plan, released in October, sets the demand charge at 85 percent. This charge is meant to cover the cost of infrastructure needed to bring electricity to those facilities; a data center must pay it if even if less electricity is used in a given month. The October proposal also would require data centers and cryptominers using more than 25 MW per month to:

- provide proof they are financially viable and able to meet the plan’s requirements; and

- pay an “exit fee” if a project is canceled or they unable to meet obligations outlined in their service agreement.

The requirements would be in place for up to 12 years, including a four-year ramp-up period. AEP Ohio says its revised plan also creates a sliding scale that would give small and mid-sized data centers more flexibility, and outlines a process to end its March 2023 moratorium.

Another AEP utility, Indiana Michigan Power, in July filed a data center tariff proposal with the Indiana Utility Regulatory Commission, seeking 20-year contracts for users of 150 MW or more, with a minimum monthly demand charge of 90 percent of contract capacity.

In North Dakota, Public Service Commission Chairman Randy Christmann in September said the legislature should address data centers in its 2025 session, as more oversight will be needed to keep the state’s power grid functional. Christmann, a former legislator, says there is enthusiasm for attracting data centers, especially to the state’s oil-producing regions where natural gas — a byproduct of oil production that must either be burned off or transported elsewhere by pipelines — could provide the power.

That’s good, he says, but legislators need to consider what happens if data centers locate in an area where the local utility or electric co-op can’t handle the load demand or afford to build new transmission lines.

“I’m putting it out there … so people understand it is a potential issue,” Christmann says. “I’m not looking to take a heavy regulatory hand, but with nothing, there is the potential for bad things happening.”

“I’m putting it out there … so people understand it is a potential issue,” Christmann says. “I’m not looking to take a heavy regulatory hand, but with nothing, there is the potential for bad things happening.”

The commission currently has no direct oversight of data centers, he adds; only in cases where those facilities get electricity from a regulated utility does the agency have authority over the electrical rates sought by the utility.

Data centers: Need for water

Data centers must keep equipment cool, which can require millions of gallons of water daily. Michigan’s legislative proposals would require these centers to use municipal water systems. Andrews adds that there is a sunset provision (no incentives for new projects after 2029), giving legislators the chance to examine the impacts on water and electricity systems.

The bills include language that “encourage” those claiming tax exemptions “to take direct steps to adopt practices to mitigate negative environmental impacts,” including efforts to conserve, reuse and replace water. These steps would not be required.

Indiana officials have proposed building a 50-mile pipeline to carry up to 100 million gallons daily from the Wabash River watershed to the Limitless Exploration/Advanced Pace Research and Innovation District — a project aimed at attracting high-tech manufacturing and data center operations to a 9,000-acre site northwest of Indianapolis. That pipeline has been on hold as the Indiana Finance Authority wraps up studies of the Wabash River’s watershed and headwaters. Findings were expected to be released in December.

Examples of state tax incentives specific to data centers: Overview of program benefits and requirements in Midwest

Illinois

Offers mix of sales and use tax exemptions for items used to construct and operate data centers

Offers mix of sales and use tax exemptions for items used to construct and operate data centers- Exemptions last up to 20 years

- Requires minimum capital investment of $250 million

- Requires project to result in at least 20 permanent full-time or full-time-equivalent jobs; average pay must be at least 120 percent of average wage in host county

- Project must demonstrate within two years it is carbon neutral or meets a green building standard

- Offers income tax credit for construction of data center in underserved area

Indiana

Provides sales and use tax exemption on equipment and electricity purchases (local property tax exemption may also be available)

Provides sales and use tax exemption on equipment and electricity purchases (local property tax exemption may also be available)- Exemptions last up to 20 years for projects with capital investments of less than $750 million, up to 50 years for projects with larger investments

- Requires varying minimum investment levels based on population of county where center is located (between $25 million and $150 million)

Iowa

Provides sales and use tax refunds (between 50 percent and 100 percent depending on project size) on equipment and electricity used to operate data centers

Provides sales and use tax refunds (between 50 percent and 100 percent depending on project size) on equipment and electricity used to operate data centers- No property tax on equipment or computers

- Requires minimum investment of $200 million (some incentives available for smaller projects)

Michigan

Provides sales and use tax exemptions for equipment sold to data centers

Provides sales and use tax exemptions for equipment sold to data centers- Only applies to a co-located data center (a center housing shared data from multiple companies)

Minnesota

Provides sales tax exemption on electricity use and purchases of items used to operate data centers

Provides sales tax exemption on electricity use and purchases of items used to operate data centers- Sales tax exemption for data center project lasts for up to 20 years

- Provides permanent exemption from personal property tax on equipment

- Requires qualifying facility to be at least 25,000 square feet

- Requires minimum capital investment of at least $30 million for new centers, $50 million for refurbished centers

Nebraska

Provides mix of investment credits, sales tax refunds/exemptions and personal property tax exemptions specific to data centers; some as part of broader, tiered incentive program that is no longer accepting new applications in certain tiers

Provides mix of investment credits, sales tax refunds/exemptions and personal property tax exemptions specific to data centers; some as part of broader, tiered incentive program that is no longer accepting new applications in certain tiers- Incentives in tiered program contingent on investment of $200 million and hiring of 30 new employees

North Dakota

Provides sales tax exemption on information technology equipment and computer software

Provides sales tax exemption on information technology equipment and computer software- Facility must be at least 15,000 square feet; 50% of space used for data processing

Ohio

Provides partial or full sales tax exemption on purchase of electricity and equipment to construct, operate centers

Provides partial or full sales tax exemption on purchase of electricity and equipment to construct, operate centers- Requires minimum investment of $100 million and annual payroll of more than $1.5 million

Wisconsin

Provides exemption from sales and use tax on long list of items needed to construct, operate data centers

Provides exemption from sales and use tax on long list of items needed to construct, operate data centers- Minimum investment varies based on population of county where center is located ($50 million to $150 million)

Sources used: Stream Data Centers, Illinois Department of Commerce and Economic Opportunity “Data Center Investment Program 2023 Annual Report,” and CSG Midwest research