Seeing the promise of biomarker testing in disease diagnosis and treatment, some states are mandating that health plans cover it

Give the right treatment to the right patient at the right time.

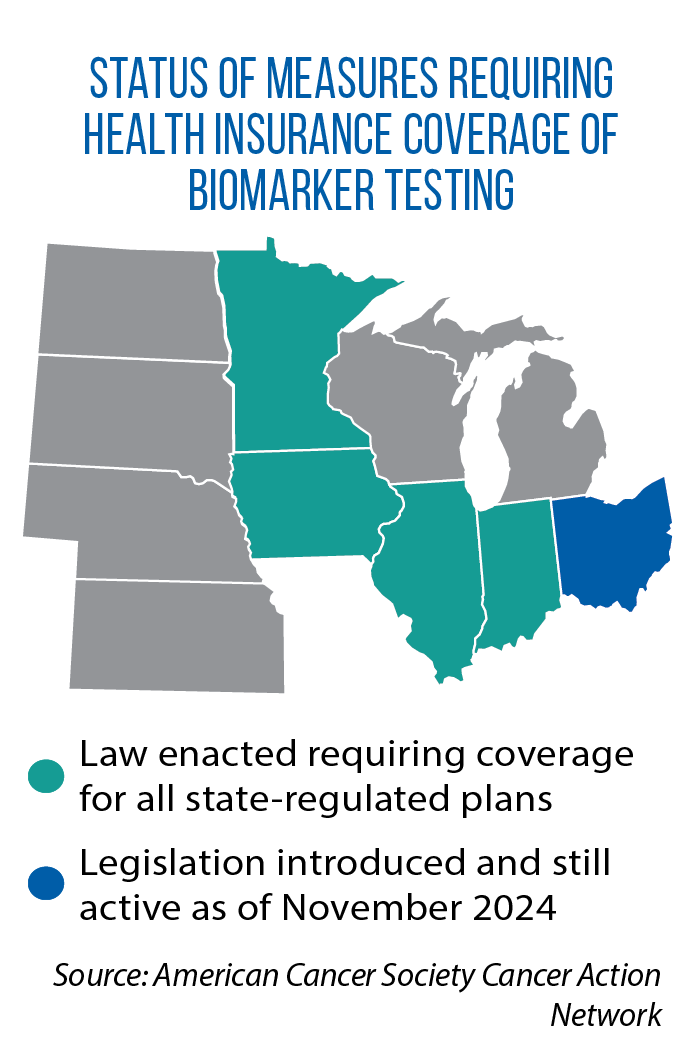

That is the promise of precision medicine, and one form of it, biomarker testing, has been the subject of a legislative trend that started in Illinois in 2021 (HB 1779). Since then, 14 other states have passed similar laws requiring health insurance plans to cover biomarker testing when it is backed by sufficient medical and scientific evidence. State Medicaid programs also often are included in these coverage mandates.

That is the promise of precision medicine, and one form of it, biomarker testing, has been the subject of a legislative trend that started in Illinois in 2021 (HB 1779). Since then, 14 other states have passed similar laws requiring health insurance plans to cover biomarker testing when it is backed by sufficient medical and scientific evidence. State Medicaid programs also often are included in these coverage mandates.

“Those who have gone through the cancer journey know that the care for cancer can take a significant toll on a person,” Iowa Rep. Brian Lohse says. “If you’re able to tailor a treatment, a cure, for an individual with biomarker testing, that toll can be limited — fewer side effects, fewer ER visits.”

He led the work on HF 2668, a bill that added Iowa to the growing list of states with a biomarker testing mandate. It passed this year with near-unanimous legislative approval, as did Indiana’s SB 273.

‘Disease agnostic’ laws

With biomarker testing, an individual’s tissue, saliva or blood is collected and analyzed for the presence of biological markers. The results can help diagnose conditions and inform decisions about treatment.

“[Doctors] can say to a patient, ‘We have found this kind of cancer with this mutation, and we have this medication to give to you that’s effective,’ ” says Grace Lin, an associate professor of medicine at the Philip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy Studies at the University of California, San Francisco. “If we didn’t have that testing, we would just go down the list of drugs, and some of them wouldn’t work at all or wouldn’t be as effective.”

“[Doctors] can say to a patient, ‘We have found this kind of cancer with this mutation, and we have this medication to give to you that’s effective,’ ” says Grace Lin, an associate professor of medicine at the Philip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy Studies at the University of California, San Francisco. “If we didn’t have that testing, we would just go down the list of drugs, and some of them wouldn’t work at all or wouldn’t be as effective.”

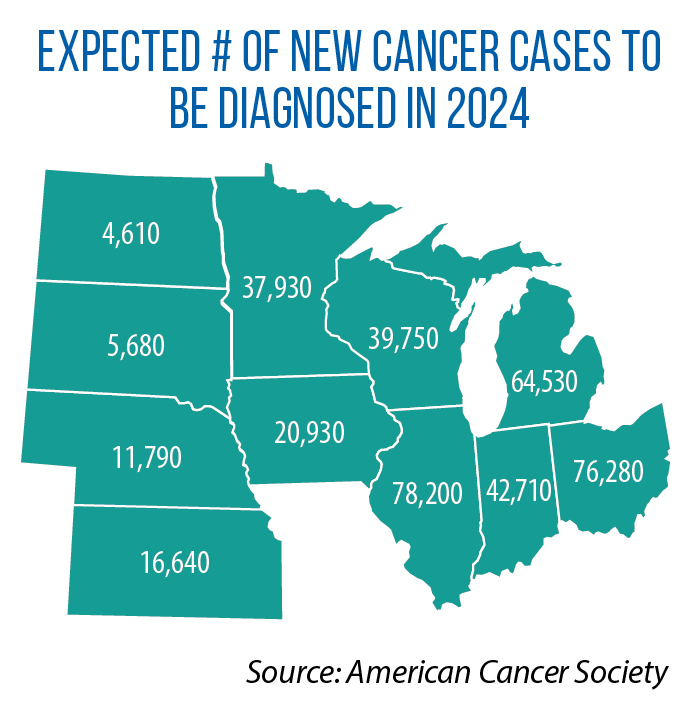

Improving access to more precise and successful treatments for cancer, in particular, has been behind the push for these new state-level coverage mandates. In some of the early-adopter states, the requirement only applied to biomarker testing for cancer.

Today, most of the laws are “disease agnostic,” and require biomarker testing whenever there is evidence of it being effective in diagnosing, treating, managing or monitoring a disease or condition. (Screening for conditions or diseases is not part of these mandates.)

Inside state mandates: Statutory language and impacts

How do states determine clinical effectiveness, the trigger that then requires insurers to cover biomarker testing?

The language in these state laws spells out several ways — for example, approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, national or local coverage decisions by the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and clinical practice guidelines or consensus statements developed by independent organizations or medical professional societies. (The National Conference of Insurance Legislators has developed model language, which Lohse says he used in crafting the Iowa bill.)

According to Lin, these laws still leave considerable room for interpretation on what is clinically useful and what is not. Her recent research on biomarker testing laws centered on another question: How effective will the new mandates be in expanding access across the state’s entire population?

Lin notes several limitations.

Lin notes several limitations.

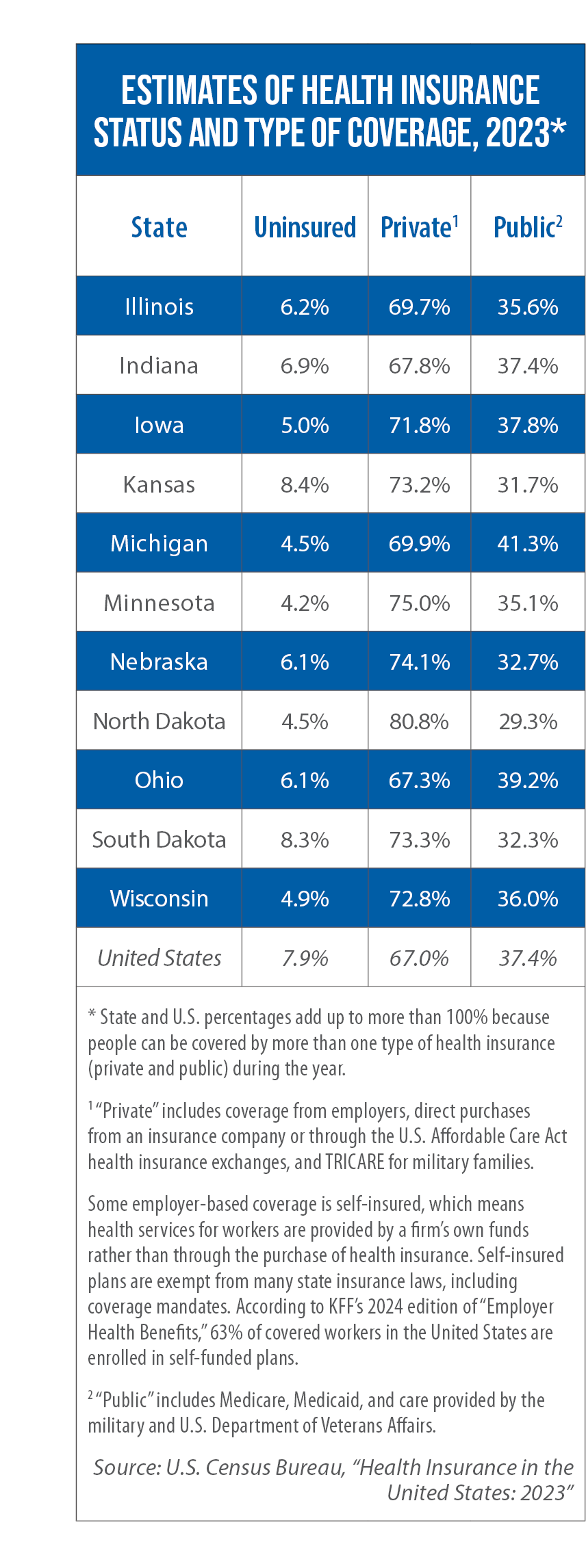

For instance, many residents are not covered by state-regulated plans, including those who are uninsured or on Medicare. Some of the laws also exclude Medicaid from the mandate. Sometimes overlooked, too, is the large number of people receiving employer-based coverage through self-insured plans, under which health services are provided to workers by an employer’s own funds rather than through the purchase of outside health insurance. Self-insured plans are exempt from state coverage mandates. According to KFF’s 2024 edition of “Employer Health Benefits,” 63 percent of covered workers in the United States are enrolled in self-funded plans.

One of the concerns raised this year in committee testimony in Ohio over biomarker testing legislation (HB 24) is that the mandate only would apply to the smaller- and medium-sized businesses that purchase health insurance. It would not touch larger-sized firms that self-insure.

Even for those individuals covered by state-regulated plans, Lin says, access to biomarker testing is uneven.

“We know already that with some of this more advanced, newer testing, there are disparities in terms of who gets it and when they get it,” she notes. “Payer coverage is one part of it, but it’s not going to solve the entire issue.”

She notes, for example, that many states now require coverage for mental health services, yet gaps in access persist.

“A lot of times, the most vulnerable people don’t get reached,” she says. “So as medicine advances, and as we get better testing and therapies, how are we going to make sure that those populations are reached?”

She suggests that legislators carefully and regularly review the impact of the biomarker testing laws. Did access increase after implementation? What can be done to close gaps in access and improve equity?

‘Wave of the future’

The new Indiana and Iowa laws do include some language on legislative oversight.

In Indiana, legislators will get an annual report on biomarker testing in the Medicaid program, including information on the number of patients who received the testing, the amount of state funding expended, the 10 most common conditions for which the testing was ordered, and results for patients (therapies used, treatments avoided, impacts of treatment).

In Iowa, by November 2025, the state Department of Health and Human Services is required to report on the number of biomarker tests provided during the fiscal year and the costs incurred by public health insurance programs.

“There are certainly some unknowns about costs, so we want to be sure to monitor it,” Lohse says.

“There are certainly some unknowns about costs, so we want to be sure to monitor it,” Lohse says.

However, he points to studies in states such as Minnesota that have predicted only a small increase in health premiums. Minnesota’s law was enacted in 2023 (as part of the omnibus SF 2995). Prior to passage of the measure, as statutorily required for any legislation calling for a new coverage mandate, the Minnesota Department of Commerce conducted a review of potential impacts. For the nonpublic insured population, the department estimated that monthly per-member expenditures would increase by between 9 cents and 22 cents in year one and between 14 cents and 32 cents in year 10.

Lohse sees potential cost savings as well, because biomarker testing can prevent spending on unsuccessful treatments and improve long-term outcomes for patients.

“Insurers already are moving in this direction [of covering testing],” he says. “There are a whole bunch of conditions and diseases where I think biomarkers are going to be able to help. As we worked on the bill, we heard not just about cancer treatment, but conditions like preeclampsia, rheumatoid arthritis and pain management.

“It’s the wave of the future.”