In demand: More non-operators view farmland as an attractive investment, raising questions about the impacts of ‘absent landlords’ on rural areas

In recent years, many state legislatures have tightened their foreign ownership laws out of concern that, at the very least, farmland ought not to be owned by foreign adversaries.

Yet foreign owners are just one of three categories of non-operating farmland owners, the other two being corporations and investors.

While no state prevents farmland transfers to individual investors by inheritance or sale, six Midwestern states have longstanding laws that restrict corporate ownership of agricultural land.

Predominantly enacted between 1930 and 1970, these measures sought to protect the family farm unit. At the time, and today, supporters of these state-level restrictions maintain that when land is owned by the individual who farms it, the farmer and the rural community are better off.

In the Midwest, Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota and Wisconsin limit corporate ownership of farmland. These states carve out exceptions for a family farm corporation, an ownership structure that generally limits the number of stockholders, requires a familial relationship between owners, and/or stipulates that a stockholder reside on or operate the farm.

In some instances, the state-level restrictions on corporate ownership have faced constitutional challenges and sometimes been invalidated, as was the case in Nebraska. In other Midwestern states, court decisions have weakened the enforceability or scope of the measures.

Where these laws remain, questions sometimes are raised about whether they unduly limit agricultural operators’ access to capital or their ability to adapt to new or changing models of ownership. A case in point: North Dakota, where legislators reworked the state’s law in 2023 with the hope of growing its livestock industry while still protecting family farmers.

‘Local ownership is ideal’

North Dakota’s laws against corporate ownership were among the nation’s strictest.

“If a group of four or so farmers wanted to pool their resources to build an animal livestock facility operated by another individual, they would have been prevented from doing so [under the old statutory framework],” Rep. Paul Thomas says, using this scenario as an example of how the state-level restrictions were stifling growth and opportunities.

“If a group of four or so farmers wanted to pool their resources to build an animal livestock facility operated by another individual, they would have been prevented from doing so [under the old statutory framework],” Rep. Paul Thomas says, using this scenario as an example of how the state-level restrictions were stifling growth and opportunities.

Livestock farming is capital intensive, Thomas adds, and many traditional lenders tend not to venture into this industry. North Dakota’s HB 1371, signed into law in April 2023, narrowly expands corporate ownership of farmland in the state.

Now, an authorized livestock farm corporation may own or lease up to 160 acres of farmland so long as the entity has no more than 10 shareholders. Under the law, when an individual owns a majority of stocks in an LLC, or 75 percent of shares in a corporation, that shareholder must be actively engaged in farming. Thomas, a sponsor of HB 1371, explains that constituents were very leery of separating farmland ownership from local operators. That is why the law ties majority investors to operator status.

“Local ownership is ideal, as it keeps wealth circulating within the state and rural communities,” he says.

But Thomas also notes that the shift of ownership to non-operators and a rise in farm consolidations can and does happen, regardless of a state’s limit on corporate farmland ownership.

The sense that local ownership of North Dakota’s agricultural land is slipping away is backed by a 2021 U.S. Department of Agriculture study. In North Dakota, non-operating landlords live, on average, 420 miles from the rented farmland, the highest average distance among the 50 states. Additionally, more than 50 percent of North Dakota’s farmland acreage was being rented out as of 2022, one of the highest rates in the nation.

Investors as owners

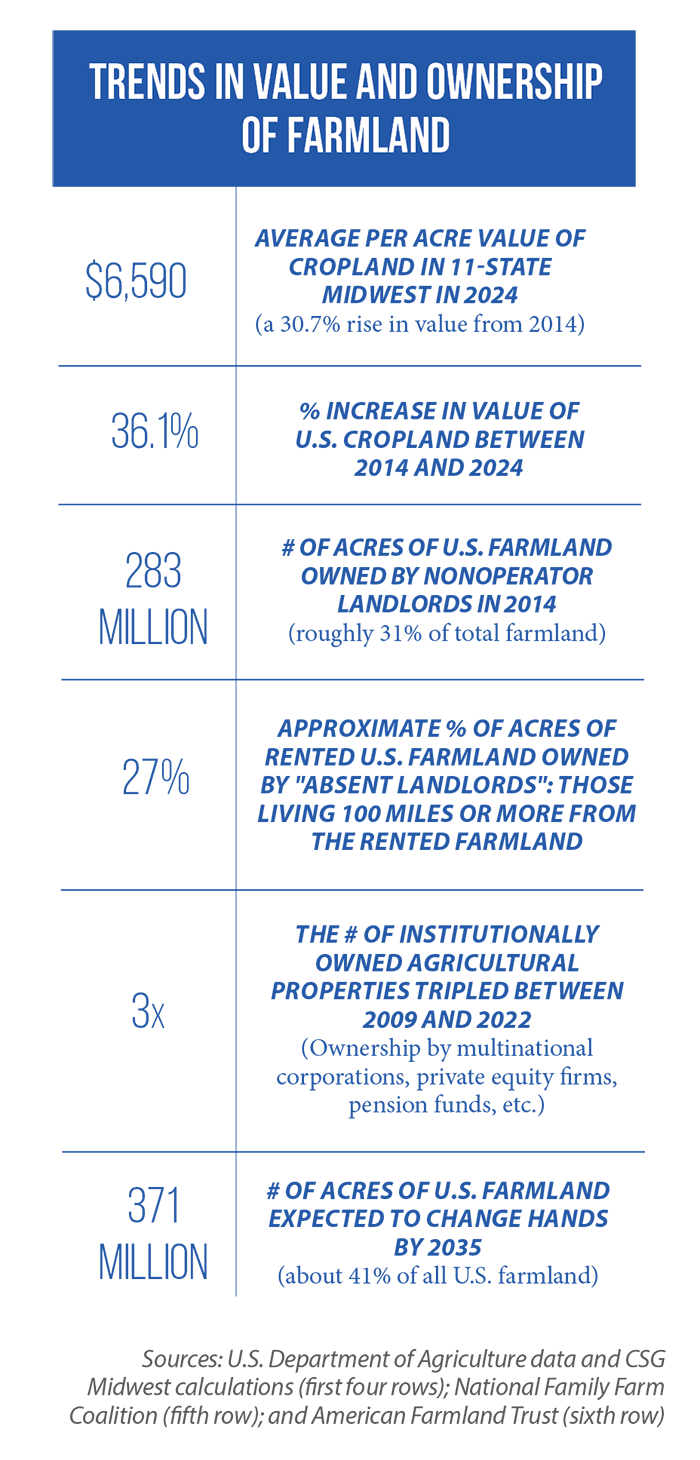

According to the USDA, 283 million acres, or 31 percent, of all U.S. farmland is owned by non-operator landlords. Most non-operator landlords have some ties to the land. Often, it was inherited and retained for any number of reasons (whether it’s the sentimental value or because the land can generate considerable rental income). There are no restrictions preventing this type of non-operator farmland ownership. Similarly, there are no restrictions on selling farmland to individual investors, a trend that often garners media attention when a billionaire purchases large amounts of farmland.

There are no restrictions preventing this type of non-operator farmland ownership. Similarly, there are no restrictions on selling farmland to individual investors, a trend that often garners media attention when a billionaire purchases large amounts of farmland.

Farmland, too, attracts interest from institutional investors: corporate entities that pool money on behalf of clients. The number of farmland properties owned by the seven largest institutional investors increased 231 percent between 2008 and 2023, and the value of those holdings rose more than 800 percent, to around $16.2 billion, according to an 2023 investigation by Reuters.

André Magnan, a University of Regina sociology professor who studies farm financialization, explains that while a vast majority of sales are farmer-to-farmer, agricultural land is increasingly viewed as a smart asset by those outside the agriculture industry.

“[It] is considered a hedge against inflation, and investors believe that with a growing world population, there will be increasing demand for food,” he says.

In 2016, Saskatchewan began prohibiting pension funds and large trusts from acquiring farmland; this legislation (Bill No. 187) was introduced and passed after a private investment group sold more than 100,000 acres to the Canada Pension Plan.

Variation in state laws

Of the six Midwestern states that have laws against corporate farming, not all preclude institutional investment ownership.

For example, in Wisconsin, domestic corporations and trusts may own farmland or carry out farm operations, provided there are 15 unrelated shareholders or less and no more than two classes of shares. In Iowa, authorized trusts comprised of less than 25 beneficiaries may own up to 1,500 acres of farmland and may own even more if it is leased to the previous owner. Minnesota flatly prohibits pension and investment funds or trusts from owning agricultural land or using it for farming purposes. South Dakota’s and North Dakota’s anti-corporate-farming laws similarly restrict institutional investors, without exception.

Starting in the mid-2000s, real estate investment trusts (REITs) also began purchasing farmland in states that allow this type of ownership model in the agricultural sector. Under a REIT, individuals (as opposed to asset managers) pool resources to purchase farmland. Farmland ownership among the two publicly traded farmland REITs has increased by approximately 180,000 acres in a little over a decade.

Gladstone Land, which entered the farmland market in 2013 and focuses on niche crops, owns 9,686 acres in Michigan and Nebraska. Farmland Partners, which went public in 2014 and focuses on row cropping, owns approximately 44,000 acres in the Midwest.

In Canada, the farmland investment firm Bonnefield has $1 billion in assets under management that comprise approximately 134,000 acres across seven Canadian provinces. According to Magnan, when a landlord is an investment company in Toronto or Calgary, those rent payments end up in the hands of partners or the investors, with the result being less revenue circulating in the local economy.

Nexus to the local economy

In 2021, the USDA studied the relationship between “absent” non-operator farmland owners (those located more than 100 miles from the rental farmland) and local economic factors. It found that “the prevalence of absent landlords is associated with declining local employment rates.” When data was analyzed at the state and county levels, per capita income growth was lower in areas with higher rates of landlord absenteeism. This federal study only looked at the correlation between income levels and the prevalence of landlord absenteeism; it did not make any causal links.

Members of U.S. Congress had mandated the study as part of the 2018 farm bill, seeking to better understand, in part, the impacts of absent landlords on the economic stability of rural communities.

Fast forward to 2023, and concerns about corporate “land grabs” led to the introduction of the Farmland for Farmers Act. This congressional proposal seeks to restrict future farmland ownership and leasing by corporations, pension funds and investment funds. The bill’s supporters also say it would protect and enhance the role of states in regulating farm ownership, in line with the intent of the anti-corporate farming laws passed in the mid-20th century. For example, the proposed federal legislation spells out a role for state attorneys general and other state officials in enforcing the act. It also explicitly authorizes states to adopt their own, “more restrictive requirements” on farmland ownership.