Special property assessments, ‘green banks’ are among financing tools for states to stimulate investments in energy

The idea to let Indiana commercial property owners voluntarily tax themselves to finance renewable-energy or energy-efficiency projects began in 2021 with residential property owners seeking ways to finance a switch from septic tanks to municipal sewer systems.

When residents approached him for help in finding such financing, then-newly elected Sen. Fady Qaddoura tapped his experience as a former controller and CFO for the city of Indianapolis to file SB 405.

When residents approached him for help in finding such financing, then-newly elected Sen. Fady Qaddoura tapped his experience as a former controller and CFO for the city of Indianapolis to file SB 405.

The bill called for an interim session study to look at creating “wastewater facility improvement districts” that could use a form of property-tax-assisted financing to help pay for such conversions.

While the bill died in the House of Representatives, the idea didn’t.

In 2024, Qaddoura revised, revived and expanded it with SB 259, a measure that also would have authorized “Property Assessed Clean Energy” (PACE) financing for commercial properties.

‘Dollars working for them’

Under PACE programs, a borrower agrees to take on an additional property tax assessment that pays for an energy-related upgrade to the property — for example, HVAC improvements; installations of LED lighting, low-flow plumbing fixtures, energy-efficient windows and solar arrays; or work on the building shell.

The PACE assessment stays with the property in case of a sale (property owners, though, can opt to prepay the assessment). A PACE lien may or may not be given priority over other liens on a given property.

“This model mimics or is similar to the tax-increment-finance models that have been used in Indianapolis,” Qaddoura says. “I was inspired by that model to try to find a solution that does not cost the local government.”

PACE financing also gives taxpayers a chance to use property taxes to serve them directly, he adds. “They would see their dollars working for them.”

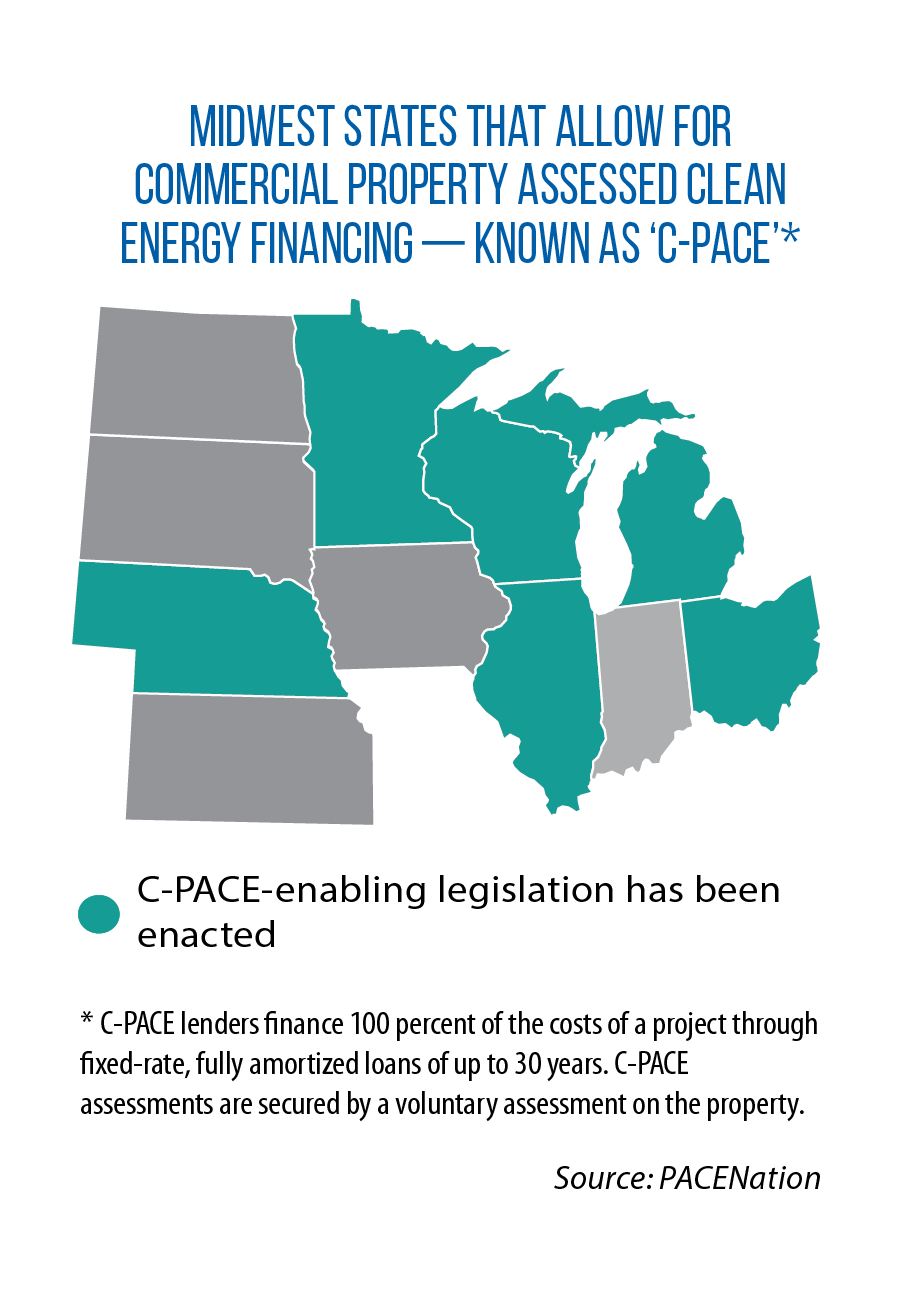

Had SB 259 been approved, Indiana would have joined the six Midwestern states already with laws allowing for commercial PACE lending: Illinois, Michigan, Minnesota, Nebraska, Ohio and Wisconsin.

PACE lending must first be enabled by a state legislature and then locally by city or county ordinance.

In some cases, the local government may provide the PACE financing itself for a project; more commonly, the upfront capital comes from a third-party lender. Still, the local government plays a critical role as remitter and collector of the PACE assessment.

In some cases, the local government may provide the PACE financing itself for a project; more commonly, the upfront capital comes from a third-party lender. Still, the local government plays a critical role as remitter and collector of the PACE assessment.

According to PACENation, an association of organizations that provides PACE financing, 40 states have adopted commercial PACE-enabling legislation. Only three (California, Florida and Missouri) have authorized residential PACE programs.

Residential programs are rarer in part due the PACE tax lien’s superior position vis-à-vis other loans, including mortgages, according to a study published in the March 2024 edition of the Journal of Environmental Economics and Management.

In the Midwest, the six states with enabling legislation only allow for this financing tool to be used on commercial property. It is known as C-PACE.

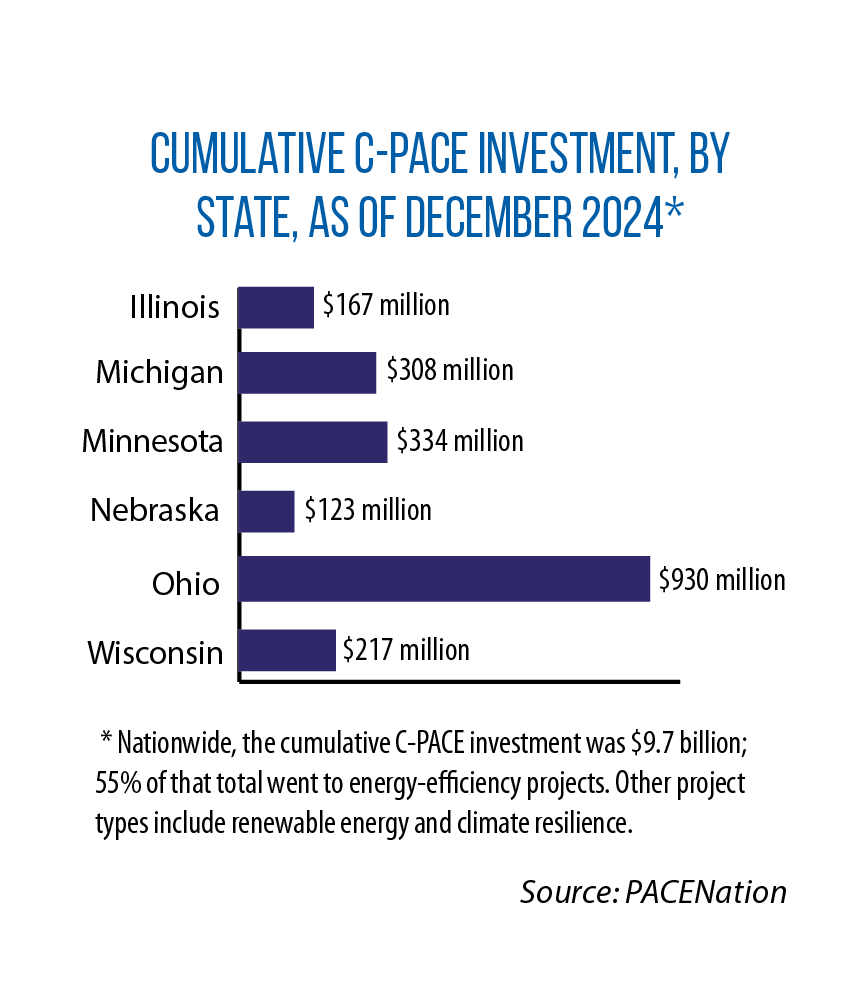

As of the end of 2024, $9.7 billion in C-PACE financing had helped pay for 3,581 projects nationwide, according to market data gathered by PACENation. In the Midwest, Ohio has had the largest cumulative C-PACE investment, $930 million.

A recent statutory change in that state also added a new option: allow a state entity itself, the Ohio Air Quality Development Authority, to use C-PACE financing to fund energy improvements at commercial or industrial sites.

This authorization came from HB 33, Ohio’s budget bill.

Christina O’Keeffe, the authority’s executive director, says this option should help bring the capital needed for energy upgrades in rural or underserved areas that “have more difficulty securing investors or lending.”

Christina O’Keeffe, the authority’s executive director, says this option should help bring the capital needed for energy upgrades in rural or underserved areas that “have more difficulty securing investors or lending.”

In late 2024, the authority announced its first project under the new law: More than $1.6 million in bond financing for energy upgrades at a vacant church in Cincinnati being converted into a modern event venue.

This financing will cover the upfront costs of energy-efficiency projects at the 156-year-old structure. The loan then gets repaid over time through the special PACE assessment. (The city of Cincinnati needed to approve this special assessment for the property.)

A second option: Green banks

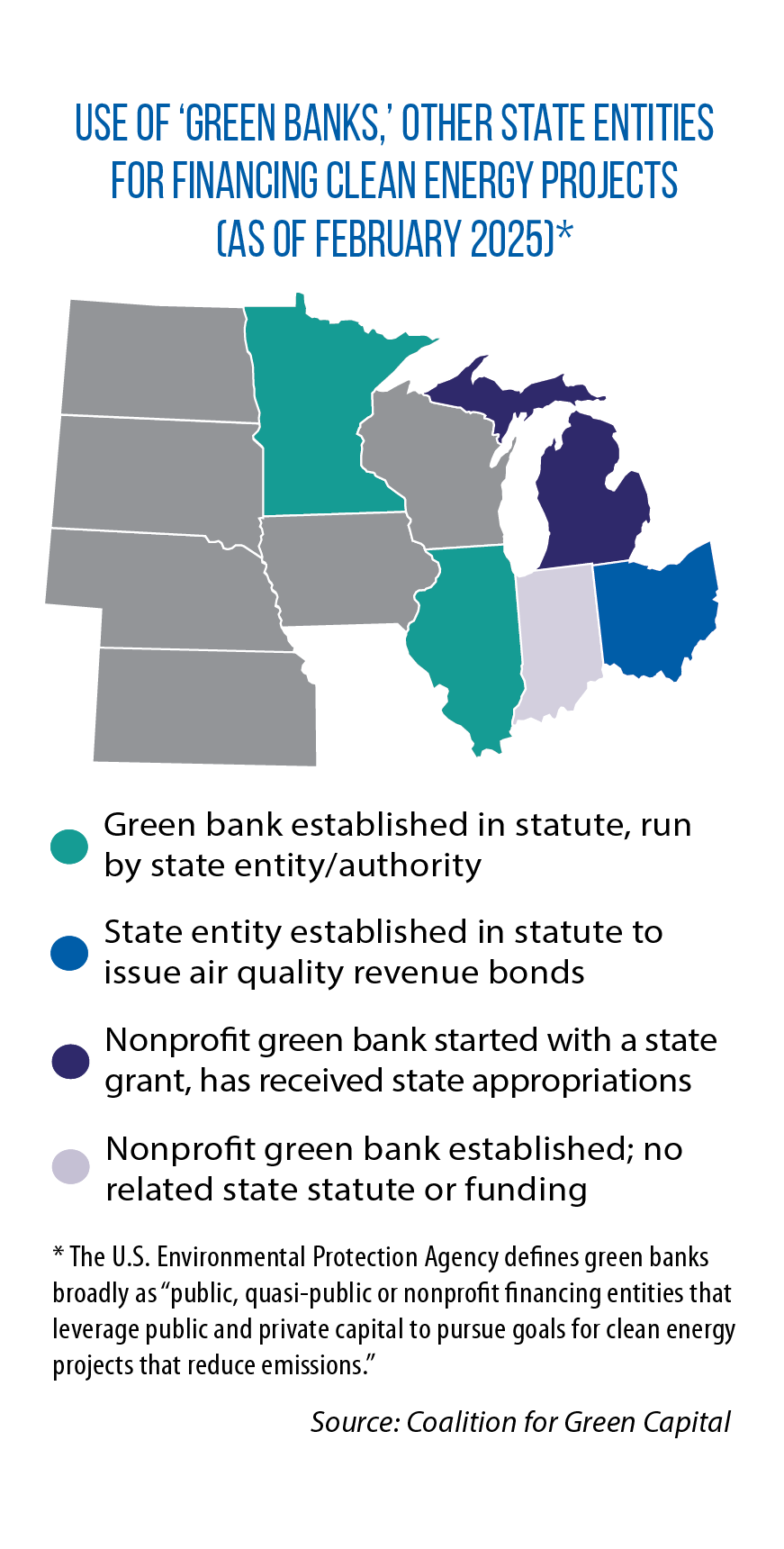

PACE funding is one tool states can employ to help residents and businesses finance energy-efficiency projects. Its more generally known fiscal cousin, the “green bank,” is another.

In the Midwest, four states have state-led and/or -supported green banks or have a state entity that functions like a green bank, which is dedicated to financing clean energy projects rather than maximizing profit, according to the Coalition for Green Capital.

Their initial capital can come from federal grants, state funds, utility bill surcharges (or a mix of two or more sources). For example, the Illinois Climate Bank is charged with distributing federal clean energy funding from the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022, while Michigan and Minnesota provided state funds to launch their respective green bank programs.

(The IRA also created the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund within the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, which acts as a federal green bank; in 2024, it obligated $27 billion in grants for clean energy programs ranging from retrofitting homes to renewable energy projects.)

In Wisconsin a pair of 2024 bills, AB 1220 and SB 1106, would have created the “Public Bank of Wisconsin” and charged it with 14 functions including financing economic development and affordable housing programs, social justice efforts, student loans, and “expansion and development of public and private measures to mitigate the grave dangers that climate change poses to the public and local enterprises, and to promote reductions in greenhouse gas emissions.”

Funding would have come from the phased-in deposit of “all public moneys” over a four-year period from 2025 to 2028. The legislation failed to advance.

Overview of 'green banks' or similar entities in Midwestern states (as of April 2025)

Illinois

The Illinois Climate Bank was established in 2021 as part of a landmark energy law (SB 2408).

Overseen by the Illinois Finance Authority, which has a 15-member board appointed by the governor and confirmed by the Senate, the bank has helped finance grid resilience and electric vehicle charging station projects, operated a revolving loan fund for energy efficiency, and recently secured $156 million in federal funds to expand access to solar energy.

Additionally, under legislation passed in 2024 (SB 3597), local governments now have the option of securing a loan from the Illinois Climate Bank to finance their own clean energy projects. The goal: give local governments access to lower borrowing costs.

Michigan

Michigan Saves operates outside of state government, as a nonprofit green bank.

The state Public Service Commission provided seed money in 2009 to start Michigan Saves, and the green bank also has received state appropriations ($5 million in the current budget).

It partners with private lenders to offer affordable financing and other incentives to property owners. Most projects are for energy upgrades to residential homes.

Minnesota

The Climate Innovation Finance Authority was established in 2023 (SF 3035) and has a 13-member board: the heads of six state agencies and seven gubernatorial appointees.

It uses state funds to invest in clean energy projects, with a focus on bringing capital to underserved communities.

The Minnesota Legislature appropriated an initial $45 million to the authority.

Ohio

Established 55 years ago, Ohio’s non-regulatory, independent Air Quality Development Authority is overseen by a governor-appointed, Senate-confirmed board.

In 2023, the authority issued more than $431 million in air quality revenue bonds to 15 different projects. The single largest investment was $275 million to support construction of a large-scale “agrivoltaic” facility, which allows for new solar generation and farm production on the same land.