States already play key role in disaster aid, recovery — and may be required to do more

Know your risk. It is common advice for residents and businesses about the potential impacts of natural disasters.

But what about state governments themselves?

Several factors are driving states to reassess their own disaster-related fiscal and economic risks, and to implement policy changes. Here is a look at three of those factors, plus how states are trying to do more in terms of long-term budget planning and risk mitigation.

More common and costly

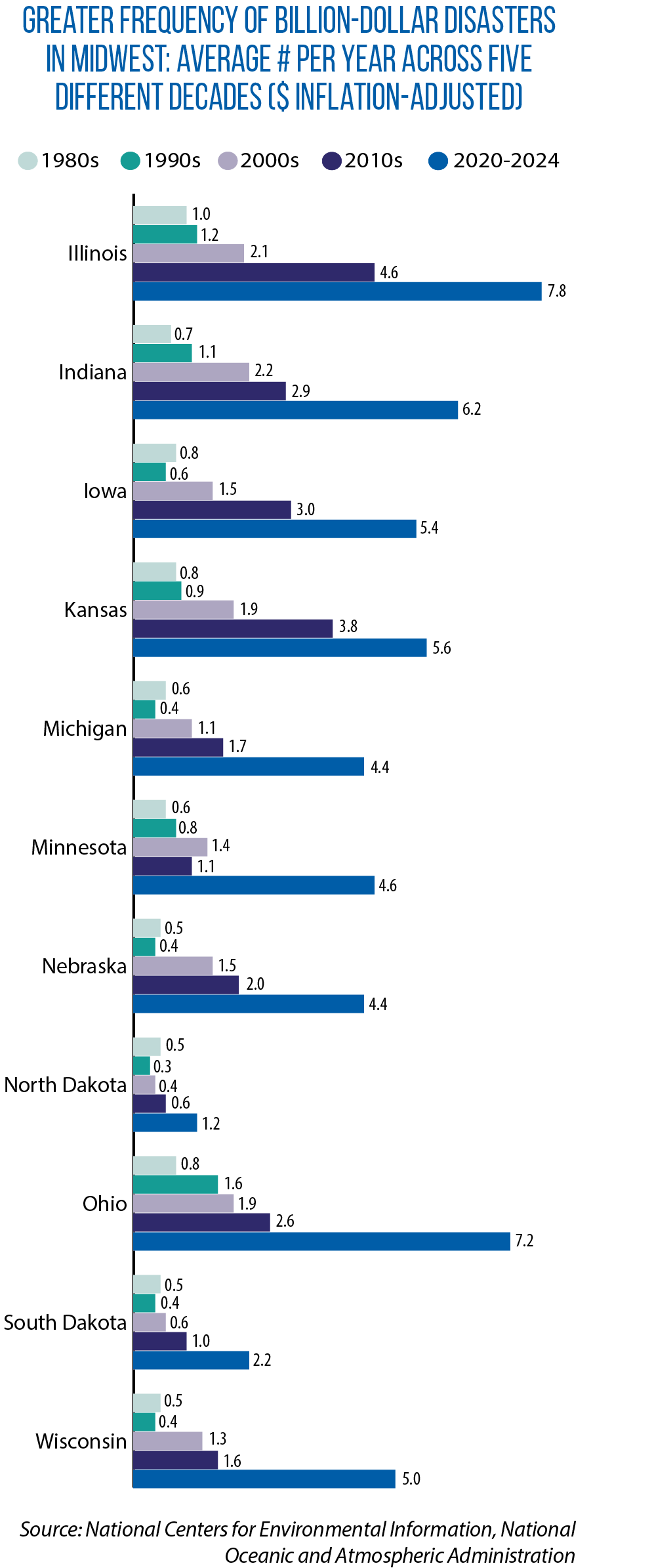

First, the number of high-cost natural disasters is on the rise in every Midwestern state, often dramatically so.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration tracks the frequency of billion-dollar disaster events over time, with costs adjusted for inflation. During the first half of this decade, every state in this region had experienced a doubling, tripling, quadrupling or more in the frequency of these events compared to the 2000s.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration tracks the frequency of billion-dollar disaster events over time, with costs adjusted for inflation. During the first half of this decade, every state in this region had experienced a doubling, tripling, quadrupling or more in the frequency of these events compared to the 2000s.

Between 2020 and 2024, the average annual number of billion-dollar disaster events in Midwestern states ranged from 7.8 per year in Illinois, up from 2.1 in the 2000s, to 1.2 in North Dakota, up from 0.4 in the 2000s. (See the bar graph for trends in each Midwestern state.)

Federal assistance comes when a disaster reaches a certain threshold, but a cost share from state and/or local governments is required. Additionally, states take on the financial responsibility for smaller-cost natural disasters within their borders.

More responsibility?

A second factor for lawmakers to consider: potential changes in the federal-state relationship.

Recent policy proposals from the nation’s capital have included raising the threshold for federal disaster assistance, leaving more planning and recovery to states, or even eliminating the Federal Emergency Management Agency altogether.

“The idea of states taking on a larger role in managing their disasters, and the federal government being involved in fewer and only the larger ones, has a lot of energy behind it right now,” says Andrew Rumbach, a senior fellow at the Urban Institute.

Higher costs of insurance

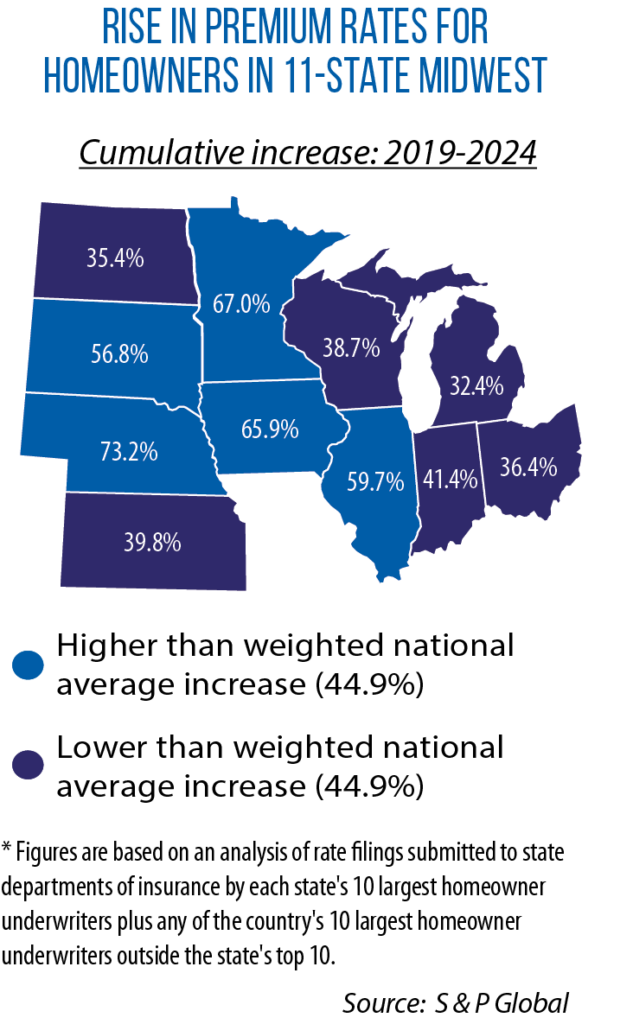

A third factor is the economic burden of rising property insurance costs on homeowners and businesses. Between 2018 and 2022, average homeowners’ insurance premiums outpaced the rate of inflation by 8.7 percent, the U.S. Department of the Treasury noted in a January 2025 report.

“It’s the significant rise in catastrophic losses and a rise in uncertainty; larger and more unpredictable losses make for a really challenging insurance market,” says Daniel Schwarz, a professor of law at the University of Minnesota.

He also points to persistent problems in the state-regulated insurance market — for example, government policies that keep premiums artificially low in areas most at risk of natural disasters.

According to the U.S. Treasury report, premium increases were sharpest in disaster-prone parts of the country. However, consumers in relatively low-risk states such as North Dakota are being hit as well.

“We’re not immune from it because of the way insurance works — the pooling of risks and the costs of reinsurance,” North Dakota Insurance Commissioner Jon Godfread says. “I think we’re in a better position than a lot of other states, but that’s still a tough sell for our consumers here who are seeing rate increases, especially given the inflationary times that we’ve been in.”

A first step: Measure your state’s disaster costs

Colin Foard, director for The Pew Charitable Trusts on a project helping states better manage their fiscal risks, suggests that leaders adjust to this era of higher-frequency, higher-cost natural disasters with a three-step approach: measure, manage and mitigate.

Measure means cataloging and reporting on how much the state is spending on disasters.

“That has been a challenge because the spending is intergovernmental and, even within the state, may occur across many different government agencies,” Foard says. “That makes it harder to track or get a holistic assessment. Also, disaster spending is a volatile cost, or least it has been. So there may be many years where it’s just not getting the attention of policymakers.”

He points to Minnesota as a leader in trying to get a handle on the ongoing budgetary impact of natural disasters.

Eleven years ago, the Legislature established a separate disaster-assistance contingency account to improve fiscal planning as well as the state’s on-the-ground assistance for individuals and communities.

Prior to creation of the account, the timeliness of that assistance (critical in the aftermath of a disaster) was dependent on legislative approval of supplemental appropriations. Under that same law, at the start of each calendar year, legislative budget leaders are provided details on state expenditures for disasters, as well as information on the status and balance of the account.

This kind of commitment to measuring costs gives legislators the data they need to manage fiscal risks over the long term, says Peter Muller, a senior officer with the Pew project.

More saving for rainy days

According to a 2020 study from Pew, states have typically covered the costs of natural disasters through supplemental appropriations, rainy day funds and/or separate disaster relief accounts.

With rainy day funds, for example, 35 states either explicitly authorize the use of these general savings accounts for use in disasters or provide enough legislative flexibility to do so. However, upward adjustments in how much is being put into rainy day funds may be needed to account for the increased frequency and costs of natural disasters.

It is common for states, too, to have separate disaster accounts, sometimes with a dedicated source of funding. In Indiana, a tax on fireworks goes to the State Disaster Relief Fund, which reimburses individuals and communities for costs not covered by private insurance or federal aid. Last year, legislators increased the maximum payout in this fund to disaster-impacted individuals from $10,000 to $25,000; that same measure, SB 190, expedites access to state aid by changing how a local disaster can be declared. (A U.S. Small Business Administration declaration is no longer required.)

Wisconsin dedicates a portion of its petroleum inspection fee to disaster assistance for local governments, and under statutory language in North Dakota, a share of oil and gas tax revenues goes to the state’s Disaster Relief Fund.

Still, the amount of money in many state-run disaster-relief accounts may be insufficient due to the lack of a dedicated, consistent or adequate funding source, or because of the greater frequency of natural disasters.

Last year, with the passage of HF 5216, Minnesota legislators sought to shore up the availability of funds in the state disaster-assistance contingency account. Now, during times of relatively high budget surpluses, money from the general fund will automatically be transferred to this stand-alone account.

The amount can be as much as $50 million.

Under legislation passed this year in Iowa, SF 619, some money from an existing economic emergency fund will be shifted to the state Department of Management for disaster relief, recovery and aid. This movement of funds would occur automatically if money in the economic emergency fund hits a statutory maximum.

The Iowa Department of Management, or other agencies, can then allocate the funds immediately in response to a governor-declared emergency.

“It’s important for states to have a way for funds to be tapped really quickly in the event of a disaster,” Rumbach says. “You want to be able to get communities back online as quickly as possible, get them operating again. That is really important for their recovery, but also for the tax revenue of state and local governments.”

Faster returns on mitigation

Iowa was hit especially hard last calendar year by natural disasters — three presidential declarations within the span of just two months due to severe storms, flooding and tornadoes.

In the aftermath of those events, one immediate priority became housing for displaced residents. Iowa partnered with FEMA on a plan to get individuals immediate shelter, first by providing recreational vehicles and trailers as interim housing and then coordinating a program to get them settled into more-permanent arrangements.

Iowa had never attempted such a rapid response to meet these housing needs, Iowa Homeland Security Director John Benson says, but it likely will be used again in future recovery efforts.

The 2024 experiences also led Gov. Kim Reynolds to call for a series of legislative changes this year. Her proposals include accelerating the construction of new housing (for example, tax exclusions for developers who work with the state to build new units after a disaster) and establishing new insurance regulations that protect homeowners in times of crisis.

Many of those provisions were part of SF 619, which passed the Legislature this year with near-unanimous approval.

Benson notes, too, that the governor’s plan eyes a greater state investment in mitigation. This will be done through the creation of a state-run revolving loan fund, with zero- or low-interest loans going to local projects that reduce future risks from natural disasters.

“In years past, the thought was, OK, if I spend a dollar on mitigation, it will take me a couple of disasters to get that dollar back,” Benson says. “It’s a lot faster than that now. If we spend a dollar in mitigation now, we make it back with the next disaster.

“Because of that, we have been very aggressive about mitigation: Beat the disasters back before they even get here.”

One example of mitigation in Iowa has been the buying up of properties in flood-prone areas. In the small town of Cherokee, Benson says, considerable flood damage was avoided this past year because many homes had been replaced with green space.

At least part of the money for Iowa’s new revolving loan fund would come from a new federal grant program, the Safeguarding Tomorrow Through Ongoing Risk Mitigation. Iowa ($12 million), Michigan ($17.4 million) and North Dakota ($16.6 million) were among the 12 federal grant recipients in FY 2024.

Common types of mitigation projects include investing in upgrades to the flood-control infrastructure, implementing changes in zoning and land-use planning, and enforcing building codes that make structures more resilient to severe weather.

“Historically, states have relied much more on federal funds for mitigation,” Pew’s Muller notes. “But there’s been an increasing trend of states making their own investments.”

This means financing not only capital projects, he says, but also putting money toward the types of statewide risk assessments, planning and workforces that can ensure state funds are used wisely.

One notable example is South Carolina. Five years ago, the Legislature created an Office of Resilience and gave it three main functions: housing recovery after a disaster, mitigation against future flood risks and overall resilience planning. The state subsequently invested $200 million in a Disaster Relief and Resilience Fund.

Rumbach suggests that states also make mitigation part of their broader, long-term plans for investing in infrastructure.

“Is this project going to make us more safe or more resilient? Is it going to make future disasters cost less?” he says. “Yes, you may be adding upfront costs to a project, but if you’re making your infrastructure, big or small, more resilient, that is really a fiscally responsible thing to do.”

He points to Louisiana as a state where this kind of mitigation-based capital planning now occurs on a regular basis.

Hardening homes

Hurricane-prone states often have been among the first to explore innovations in mitigation. For example, the Alabama Legislature established a home-hardening program a decade ago. Run by the state Department of Insurance, Strengthen Alabama Homes offers incentives and grants to homeowners who “fortify” their roofs (beyond traditional building codes) against heavy winds and rains. A discount on insurance premiums is available to homeowners upon completion.

Hurricane-prone states often have been among the first to explore innovations in mitigation. For example, the Alabama Legislature established a home-hardening program a decade ago. Run by the state Department of Insurance, Strengthen Alabama Homes offers incentives and grants to homeowners who “fortify” their roofs (beyond traditional building codes) against heavy winds and rains. A discount on insurance premiums is available to homeowners upon completion.

In the Midwest, the Minnesota Legislature in 2023 established a similar program (SF 2744) to protect roofs from hail and wind damage. According to the state Department of Commerce, once this project is up and running, the projected grant amount for each qualifying home will be $10,000. Additionally, insurers will be statutorily required to provide a discount on premiums or insurance rates.

Godfread says he has watched with interest the spread of these programs and others that strive to reduce risks from natural disasters, and how they might be implemented in North Dakota.

“On the national level, more and more, I think the discussion is going to be how to construct communities that are more resilient,” he says. “You cannot continue to build the way we’ve always built and expect that insurance is going to continue to absorb these losses.”