Capital Closeup | Redistricting and state legislatures

Deadline dilemma: Census delays pose new redistricting challenges

In 2015 and 2018, two separate legislatively initiated, voter-approved constitutional amendments remade the process of redistricting in the state of Ohio. The goal: ensure more bipartisanship and curb gerrymandering in the drawing of political maps.

This new constitutional language in Ohio also included some firm deadlines on when those maps must be drawn, under the assumption that the U.S. Census Bureau would compile and release its population data as it has in the past and as set out in federal statute. But plans and schedules changed in 2021.

“The release of census data has sometimes been treated like the rising of the sun,” says Michael Li, senior counsel at the Brennan Center for Justice’s Democracy Program. “What we’ve learned is that it usually works that way, but not always.” In February, the U.S. Census Bureau announced that COVID-19-related delays in data collection and processing would postpone the release of redistricting information to the states — from March 31 to a new deadline of Sept. 30.

This new release date falls right on the deadline for the Ohio General Assembly to adopt a bipartisan-approved congressional map (“the last day of September of a year ending in the numeral one”). For new state legislative districts, a seven-member Ohio Redistricting Commission is supposed to adopt a plan no later than the “first day of September of a year ending in the numeral one.”

Ohio sued the Biden administration in February over the census delays. It was the first U.S. state to do so, but is far from the only one with scheduling challenges ahead. The Iowa Constitution, for instance, requires that a redistricting plan for state legislative districts be passed by Sept. 15. After that date, the state Supreme Court takes on the responsibility of drawing the new map — with a due date of Dec. 31.

with scheduling challenges ahead. The Iowa Constitution, for instance, requires that a redistricting plan for state legislative districts be passed by Sept. 15. After that date, the state Supreme Court takes on the responsibility of drawing the new map — with a due date of Dec. 31.

Other states have statutory or constitutional language requiring that new maps be done on a specific day in the year “after the decennial census.” The census count was done in 2020. That means Michigan’s new Independent Redistricting Commission must have congressional and state legislative maps in place by Nov. 1. The South Dakota Legislature must have the new map for state legislative districts done by Dec. 1 of this year.

“One obvious lesson from this year is that when you’re drafting redistricting legislation, don’t put hard dates in there,” Li says. He notes that a section in Colorado’s recently amended Constitution allows the state’s independent redistricting commission to adjust deadlines for “conditions outside of the commission’s control.”

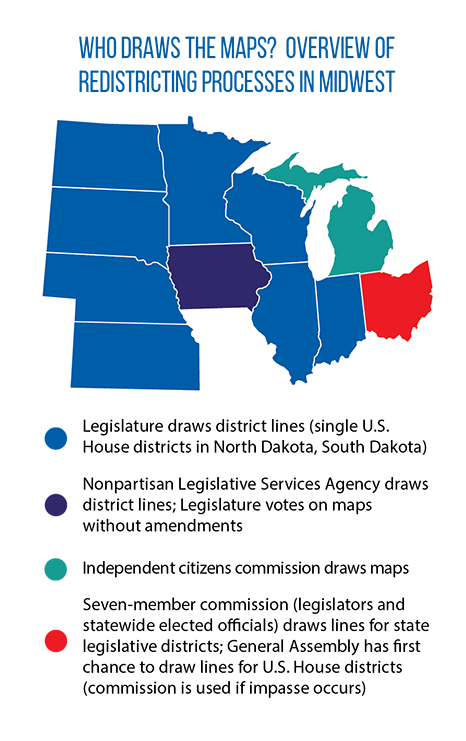

In the Midwest, redistricting is still largely left in the hands of state legislatures (see map). And some of the region’s legislatures already have some leeway on when to complete the process — there are no deadlines at all in Nebraska, for instance, and language in the Minnesota and Wisconsin constitutions call for plans to be developed at the first legislative session “after each enumeration … made by the authority of the United States.”

Li sees two challenges for states related to the delayed release of census data. One is figuring out the conflicts in deadlines; the second is ensuring that the redistricting process is done fairly, methodically and openly. Of those two challenges, the latter concerns him the most, especially because many state legislatures are likely to adopt new maps in shorter, special sessions.

“What we don’t want to see is a shortcut in the process, where hearings aren’t held, where the public doesn’t have the chance to review the maps,” he says. One option for states as they wait for the actual census information is to use alternative data (such as population statistics from the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey) for public hearings and even the release of preliminary maps. But when it comes to drawing the final maps, there is no substitute for using actual census figures.

“You’re just asking for a lawsuit, a one-person, one-vote challenge, if alternative data were to be used,” Li says.

Capital Closeup is an ongoing series of articles focusing on institutional issues in state governments and legislatures.