Illinois revamps college-level developmental education with goal of improving completion rates

This past summer, following the killing of George Floyd, legislators across the country began asking questions about racial justice and disparities in their own states. Among them was Illinois Rep. Carol Ammons, and one of her questions, along with other leaders in her state’s Legislative Black Caucus, was this: “Is this just a police issue?”

“Our answer was no,” she says.

Their legislative response was to develop a sweeping policy agenda built on four pillars: criminal justice reform, economic equity and opportunity, health care and education. Much of the work on that last pillar fell to Ammons, last year’s chair of the House Higher Education Committee. Her efforts culminated in January with the passage of HB 2170. The measure seeks changes at all levels of the education system, with an overarching goal of advancing racial equity.

On the higher-education side, one piece of that bill illustrates the kind of systematic reforms being sought. It has to do with how the state’s community colleges deliver developmental education to students, and how these institutions choose who takes part in this coursework.

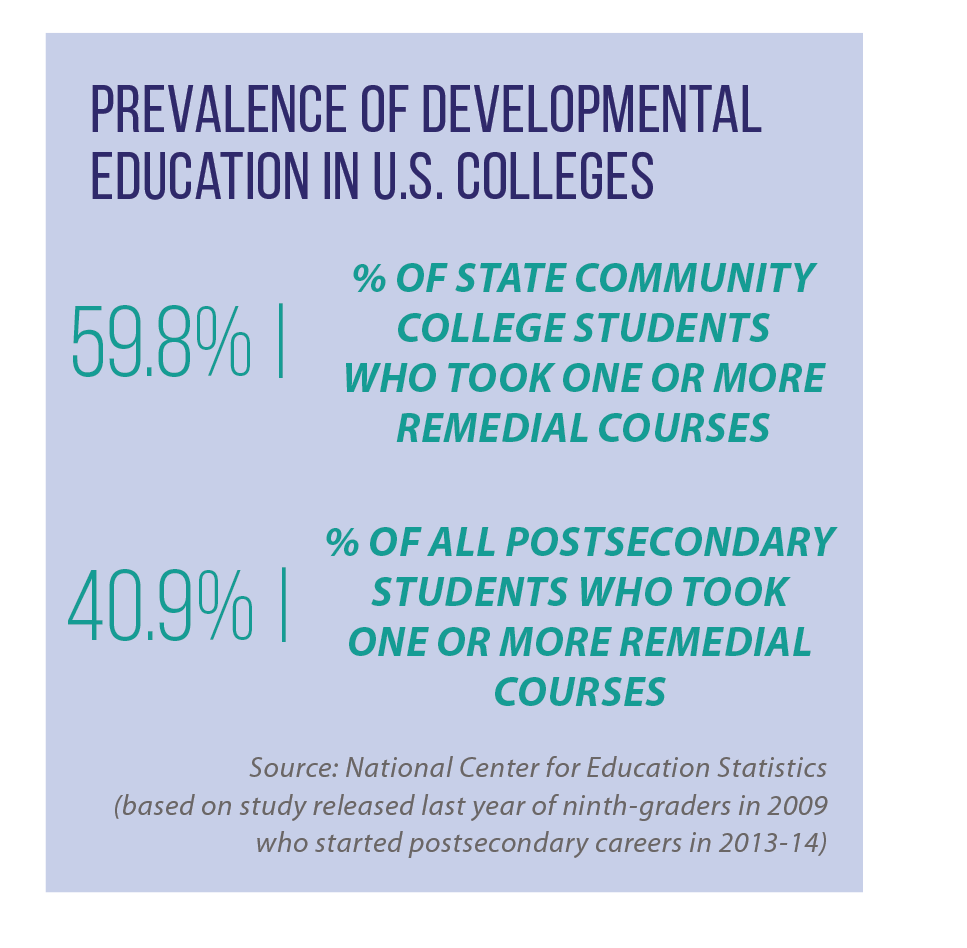

Developmental education is remedial instruction in subjects such as English and math, often traditionally taken before students can move on to college-level, credit-bearing courses. State-level reforms in this policy area became “a centerpiece,” Ammons says, in part because of what legislators learned in committee testimony over the summer. In Illinois, almost half of high school graduates enrolled full-time in a community college are placed in developmental education. Among minority students, this rate is even higher — nearly 71 out of every 100 Black students, for example, and among this group, only six of 100 go on to graduate.

“The traditional developmental-education courses cost students time, money and financial aid, but they don’t count toward college credit,” Ammons says. “It becomes a barrier.”

HB 2170 seeks to change that.

First, community colleges must look beyond standardized test scores and college-placement tests when determining who gets placed in remedial education. For example, a graduating high school student who has a high grade-point average or who has successfully completed college-level or transitional classes must be placed in credit-bearing courses. Second, HB 2170 uproots the traditional developmental-education approach, calling for it to be replaced with an “evidence-based model that maximizes a student’s likelihood of completing an introductory college-level course within his or her first two semesters.”

One likely result: community colleges’ adoption of a “co-requisite model,” under which students are placed directly into college-level coursework with concurrent instructional supports.

“What we’ve seen with the traditional model is that 18 percent of Black students in math and 29 percent in English completed a gateway course with a C or better in three years,” says Emily Goldman, senior policy manager for the Partnership for College Completion. “With the co-requisite model, it’s 69 percent and 64 percent.”

Illinois isn’t alone in seeking these kinds of policy changes. More states around the country are recognizing the traditional model as an obstacle to postsecondary completion, says Nikki Edgecombe, a senior research scholar at the Community College Research Center. The loss of time and money (including the possible exhaustion of financial aid) while taking remedial courses are factors, she notes, but so is the impact on a student’s academic outlook.

“It can be demotivating for a student, ‘I applied to college, they let me in, and now they won’t let me take college classes,’ ” Edgecombe says. “Getting students into and through their gateway courses is important to generating academic momentum.”