Iowa adds statutory language that aims to retain qualified-immunity protections for police officers

A provision in Iowa’s so-called “Back the Blue Act” cements in state statute liability protections known as “qualified immunity” for government officials and law enforcement. Although certain government actors already enjoy legal protections, the new law supplements what was previously just judicial doctrine.

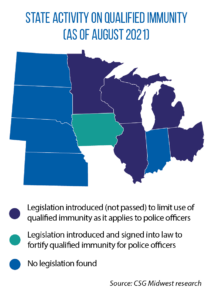

This year’s passage of SF 342 in Iowa reflects increased legislative activity around the country on qualified immunity, a type of liability protection that dates back decades and has more recently become the focus of various police-reform measures — in state capitols and Washington, D.C.

become the focus of various police-reform measures — in state capitols and Washington, D.C.

The recent changes in Iowa stand out, though, because they seek to fortify legal protections for police officers. In contrast, legislatures in Colorado, Connecticut and New Mexico have passed measures limiting the ability for law enforcement to seek qualified-immunity protections.

During legislative discussions on SF 342, Iowa Rep. Jon Thorup spoke of the difficult decision-making that officers encounter on a regular basis.

“Attorneys and judges have hours; management has hours, weeks, months to decide if what [police officers] did was right or wrong,” Thorup, an Iowa state trooper himself, said. “We only have a few seconds.”

SF 342 spells out when employees of the state “shall not be liable for monetary damages”: if the right, privilege or immunity alleged to have been deprived “was not clearly established [in law] at the time” or if it was “not sufficiently clear that every reasonable employee would have understood that the conduct [being] alleged constituted a violation of the law.”

Three years ago, in Baldwin v. City of Estherville, the Iowa Supreme Court settled on a “due care” standard (based on an existing statute on state tort claims). “To be entitled to qualified immunity,” the justices wrote, “a defendant must plead and prove as an affirmative defense that he or she exercised all due care to comply with law.”

Iowa Rep. Christina Bohannan argued in favor of this criterion, rather than the language in SF 342. “[Due care] is a better standard because it does provide immunity, but it bases that immunity on the reasonableness of the officer’s conduct,” she said.

SF 342, though, follows the direction that qualified immunity has taken as the result of a series of U.S. Supreme Court decisions: this liability protection applies except in instances where “clearly established” rights or laws have been violated, and where such violations would be clear to “every reasonable employee.”

Writing for the majority in the Baldwin case, Iowa Supreme Court Justice Edward Mansfield argued that this approach by the federal judiciary “gives undue weight to one factor: how clear the underlying constitutional law was.”

Some lawmakers have suggested that because SF 342 has language on qualified immunity that conflicts with the Iowa Supreme Court’s due care requirement, it could be deemed unconstitutional.

“It’s not as if we’re dusting off a decision from 40 or 50 years ago to find out if it’s still relevant,” Iowa Sen. Nate Boulton says. “Passing a questionably constitutional statute does not help us have the best training and education for officers on the streets; it only adds more questions, less clarity and frankly makes the job of a police officer more dangerous.”

Dave Roland of the nonprofit Freedom Center of Missouri notes that while “states have no authority over federal law or how [it] is interpreted or applied, they can pass their own versions of civil rights acts that allow citizens, pursuant to state law, to pursue constitutional claims against officials.”

Last year, Colorado became the first U.S. state to act on this authority. SB 217 allows individuals to initiate civil actions against an officer for violating their rights under the state Constitution. The law also specifies that qualified immunity is not a defense to these civil actions.

Meanwhile, certain federal court systems have begun to push back on excusing liability. This year, in two separate cases, the 8th Circuit Court of Appeals — which encompasses multiple Midwestern states, including Iowa — ruled in part against officers’ requests for qualified-immunity recognition.