In Nebraska, new law allows meat consumers to own ‘herd shares,’ and producers to make direct sales

When it first hit, the COVID-19 pandemic turned much of the Midwest’s meat processing industry upside down.

And though normalcy has largely returned to this sector, some changes appear to be more permanent: greater consumer demand for locally grown and processed meat, and new economic opportunities for smaller-scale producers and processing facilities.

For states, the most common response has been to establish grant programs (often with the help of federal dollars) for smaller processing plants to increase capacity and modernize operations. Nebraska included this approach in LB 324, a measure passed earlier this year without a single “no” vote. But the new state law also includes a more novel approach to help the state’s livestock producers — allow their consumers to have a form of ownership, through what Nebraska Sen. Tom Brandt refers to as a “herd share agreement.”

“[It] expands the definition of ownership to allow livestock producers to offer home-raised meat that is processed at custom-exempt plants,” says Brandt, who has a background in commercial meat processing and livestock production. He sponsored LB 324, which took effect in August. Under a herd share agreement, a consumer is able to buy a steak or hamburger from the farmer by purchasing a share of the live animal before it is processed at a custom-exempt plant.

This change in state law provides a workaround of a federal requirement that the meat from custom-exempt plants be consumed only by the owner of the animal. (These plants are only reviewed periodically by federal inspectors.)

To participate in a herd share agreement, a producer must provide the share owner with a description of livestock health and processing standards, as well as maintain a record of each animal share sold. “LB 324 established a set of guidelines to ensure compliance with state and federal law and documentation to prove ownership and to address food safety concerns,” Brandt says. The producer must reside in Nebraska and register with, and report sales to, the state Department of Agriculture.

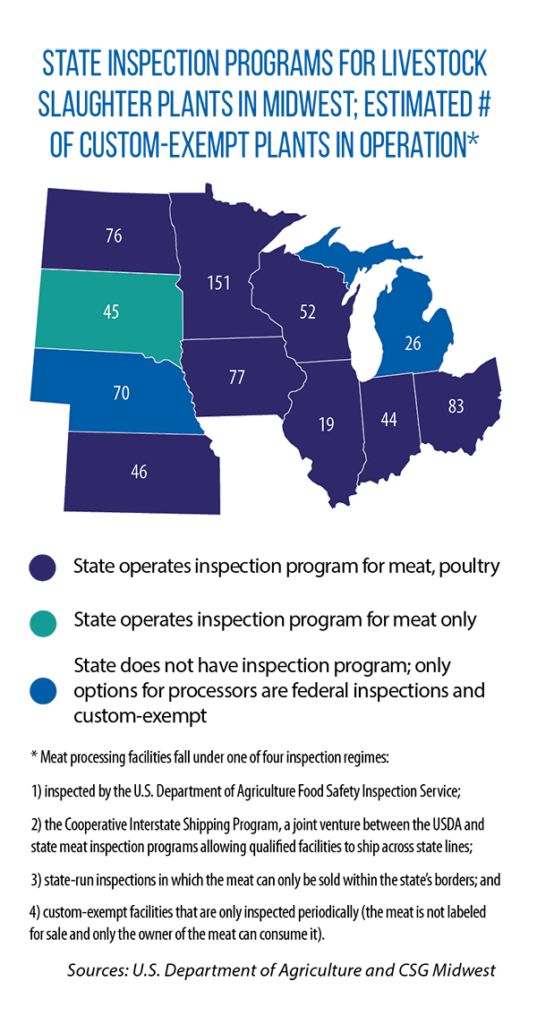

Nebraska is one of two states in the Midwest (Michigan is the other) without a state-run meat inspection program. As a result, only one of two kinds of meat processing plants operate in Nebraska: those that are federally inspected or custom-exempt. According to the Center for Rural Affairs, some smaller-scale operations prefer state-run programs, noting federal inspectors are more accustomed to working with larger plants. (For instance, facilities are expected to construct a designated office and have a shower available for the inspector.)

“State inspections … help decrease the burden of opening or maintaining a small locker or processing facility,” the center says. Cost concerns ended Nebraska’s state-run inspection program decades ago, and Brandt says that remains an obstacle to re-establishing one. While the U.S. Department of Agriculture fully funds federal meat inspections, states are expected to cover half of the costs of their own programs.

Still, most states in this region have chosen to offer inspections. This then enables a fourth type of inspection program, a state-federal collaborative that permits interstate shipments and sales of meat from state-inspected facilities.