In Illinois and elsewhere, prisons’ treatment and care of transgender offenders is under increased scrutiny

A federal judge has ordered the Illinois Department of Corrections to take a series of steps over the next few months to better address the needs of incarcerated transgender persons.

U.S. District Court Judge Nancy Rosenstengel criticized the overall rate at which change is occurring at the Illinois Department of Corrections. “It’s like a physician ordering a cholesterol test, the results coming back over 300, and yet the physician does nothing but put the lab results in the chart,” she wrote in her August order.

Beginning in 2019, the U.S. Southern District Court of Illinois ruled in favor of a group of transgender offenders who have accused the state of improperly caring for their wellbeing.

At issue are instances of transgender offenders being denied hormone therapies for unfounded reasons, medical staff not versed in concepts such as gender dysphoria (psychological distress resulting from an incongruence between one’s sex assigned at birth and one’s gender identity), an improper handling of strip searches, a lack of privacy granted in showers, and IDOC staff misgendering offenders.

In her August order, Rosenstengel acknowledged some improvements, including mandatory staff training.

In addition, IDOC has formed two committees to improve transgender care. One has been tasked with reviewing issues related to medication delivery and gender-affirming surgeries; the second is reviewing security protections and logistics regarding prison transfers.

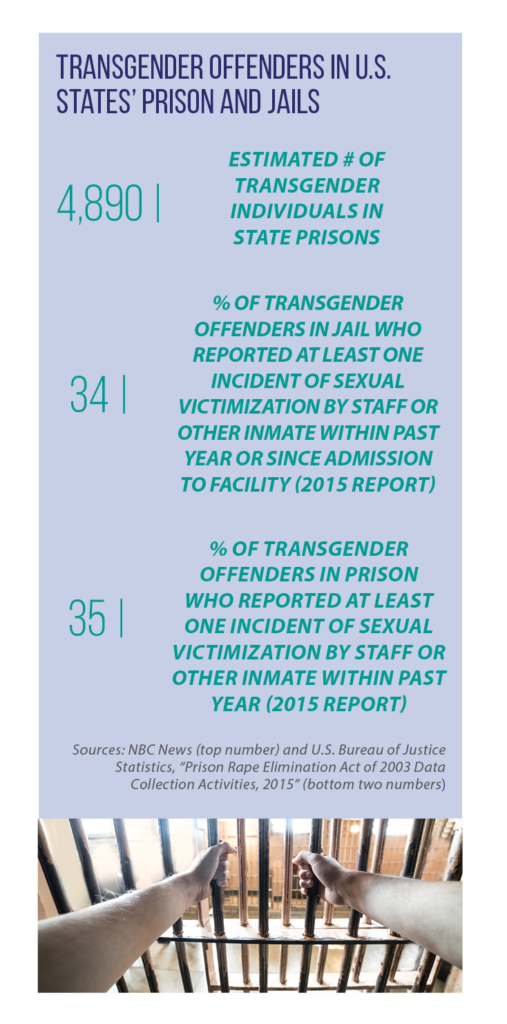

Under the U.S. Prison Rape Elimination Act of 2003, prisons must regularly interview transgender offenders to determine where they would feel the safest, a men’s or women’s facility. However, executing transfers has proven difficult nationwide. According to NBC News research conducted last year, among the nation’s estimated 4,890 incarcerated transgender individuals, only 15 were confirmed to have been transferred to a facility that matched their gender identity (including one in Illinois and one in Iowa).

One explanation for the low number of transfers, some transgender activists say, is that offenders may place greater stock in their personal safety and dignity over facility type. “I think transgender people should be housed in the housing that they want to be housed in,” Shelby Chestnut of the Transgender Law Center says.

But Chestnut adds that the real damage occurs when an offender is denied gender-affirming resources, such as access to types of clothing or hygiene products. Compared to their cisgender counterparts, too, transgender offenders are more likely to experience instances of sexual abuse, attempt suicide, and be assigned to solitary confinement “for their own safety” — a phenomenon that puzzles National Center for Transgender Equality Executive Director Rodrigo Heng-Lehtinen. “If solitary confinement is so demoralizing that it’s used as punishment … how is it also keeping someone safe?” he asks.

He adds that state legislatures have the ability to address many of these issues. Some recently enacted laws outside the Midwest, for example, require people to be placed in prisons that match their gender identity.

Proposals in Wisconsin this year (AB 467 and SB 443) would create a “Transgender Equality Taskforce.” One of the subject areas: prison policy.

“We would expect…experts who work in the criminal justice reform area to come to us and say, ‘Yes, these are problems in Wisconsin and here are suggestions on how to solve them,’” says Wisconsin Rep. Lee Snodgrass, a chief sponsor of AB 467.