‘More than just trading partners’

Twenty months of a partially closed U.S.-Canada border caused hardships for communities in Midwest, provided lessons for strengthening the binational relationship

The Northwest Angle in Minnesota is surrounded by Manitoba, Ontario and water, separated from the rest of the United States by those provinces and Lake of the Woods.

When the summer boats aren’t operating, or when a winter ice road across the lake isn’t passable, the only way to get to the “Angle” (the northernmost point of the contiguous United States) is to drive about 50 miles through Manitoba.

That option disappeared for much of the past two years with the COVID-19-related closure of the U.S.-Canada border. Businesses and residents in the tourism-reliant Angle, a prime destination for walleye fishing, were left without access to the rest of Minnesota.

It is one of many communities in the Midwest whose economies, families and cultures are tied, in some way, to the relatively free and open U.S.-Canada border.

“We’re more than just trading partners; we’re friends as well,” says Manitoba MLA Kelvin Goertzen, noting that his fellow Manitobans often travel to Minnesota or North Dakota to shop or eat at their favorite restaurants, and vice versa.

Travel restrictions over the past two years created hardships for border communities, while also underscoring the two countries’ interdependence. Families and friends could not connect, and the closure of the border to “non-essential” travel kept local businesses and customers apart.

For example, a short drive of less than 3 miles across the Sault Ste. Marie International Bridge typically brings people to and from the sister cities of Sault Ste. Marie in Michigan and Ontario. Not so during the pandemic.

In the heavily populated Detroit-Windsor area, state and provincial officials had to work with their federal counterparts to ensure that workers, particularly in health care, could move to and from a job in one country and home in another.

“[There is] a lack of appreciation for how integrated the Canada-U.S. economic relationship is, and a false sense that everything was actually fine [over the past two years] because there was an exemption for so-called ‘essential commerce,’” says Maryscott Greenwood, CEO of the Canadian American Business Council and co-host of the “Canusa Street podcast,” which explores Canadian-American relations.

Still, experts on the U.S-Canadian relationship say lessons from border restrictions enacted two decades ago helped lead to smarter policy responses this time around.

Now, they believe there is more to learn from the recent, and more prolonged, shutdown.

Policy innovations helped border trade continue

The lives of Americans and Canadians living near, and far from, the border changed on March 20, 2020, the date that U.S. President Donald Trump and Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau agreed to a bilateral closure of the border to contain the spread of COVID-19.

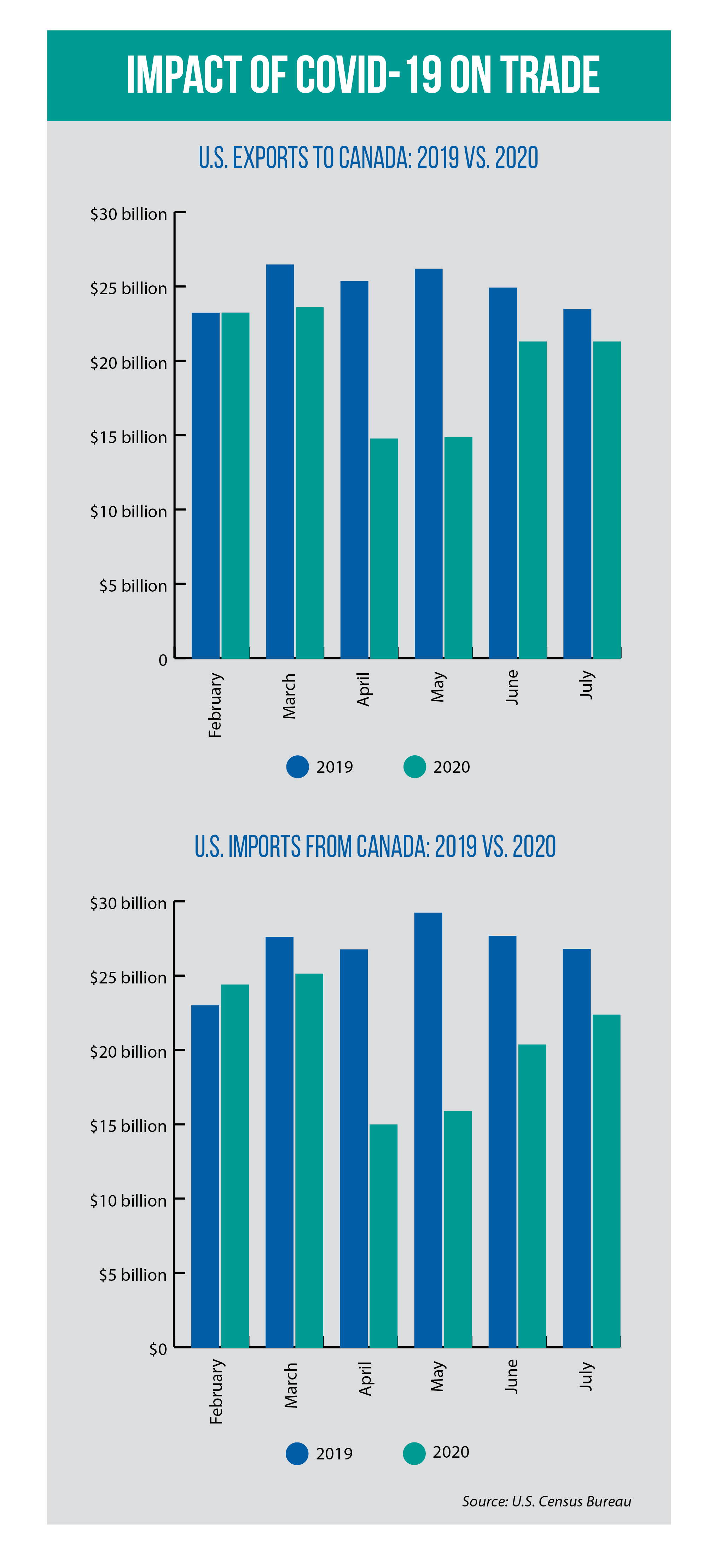

A shutdown of the world’s longest undefended border had potentially massive consequences for the economies of states and provinces in the Midwest.

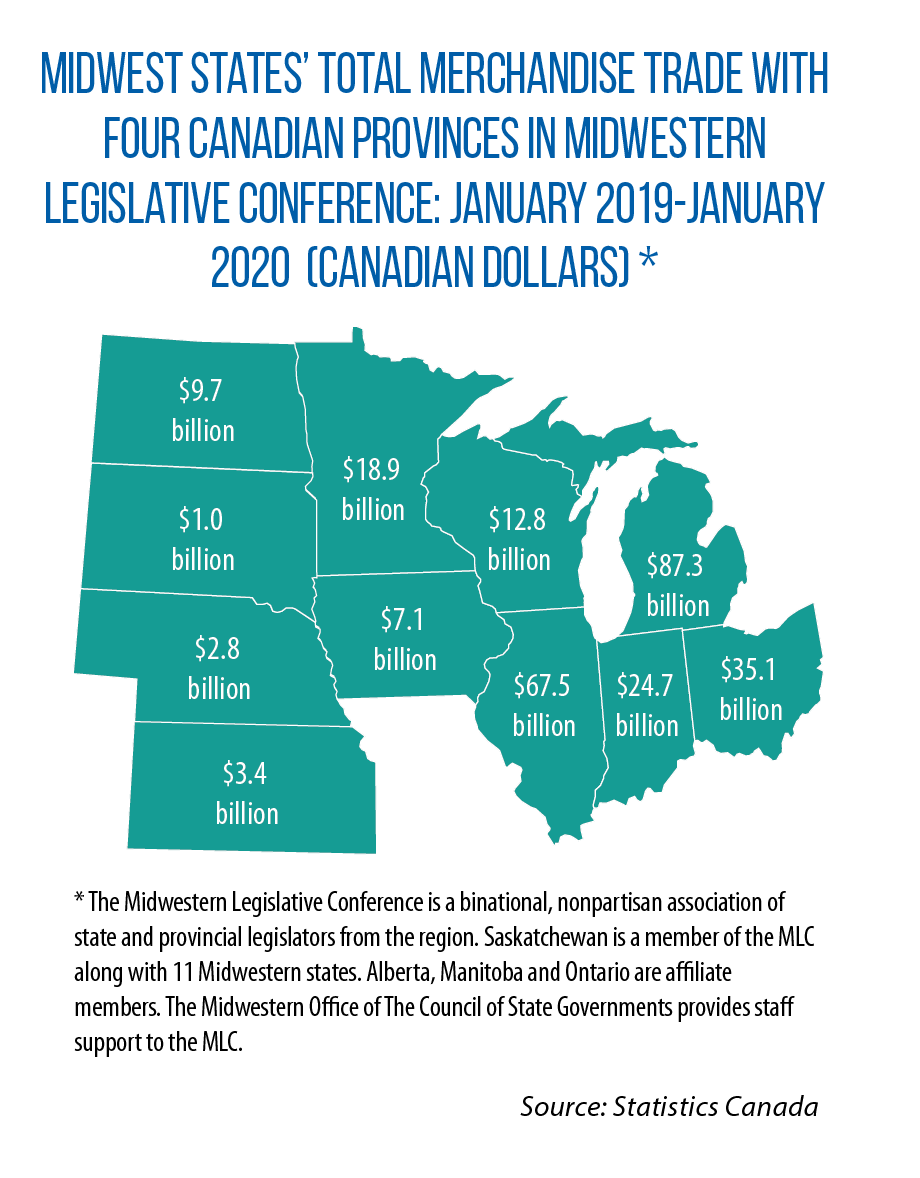

A year prior, in 2019, nearly $82 billion worth of trade (Canadian dollars) occurred between Michigan and Ontario, $41 billion between Illinois and Alberta, and nearly $31 billion between Ohio and Ontario (see table at bottom for full listing).

The last such abrupt, total closure had occurred following the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. In that instance, the restrictions were not negotiated or bilateral; they were imposed unilaterally by the United States.

In the years that followed 9/11, the two countries implemented border innovations such as separate vehicle lanes for trucking, trusted-traveler and -trader programs, customs pre-clearance, and digital cargo manifest filings.

These advances in border operations helped to limit the economic impacts of the closures in 2020 and 2021.

This time around, freight drivers weren’t stuck in miles-long queues sleeping in their trucks. Truckers were on a list of “essential” travel allowed to move across the border. That list also included, but was not limited to, cross-border movement for work and medical reasons and to attend educational institutions.

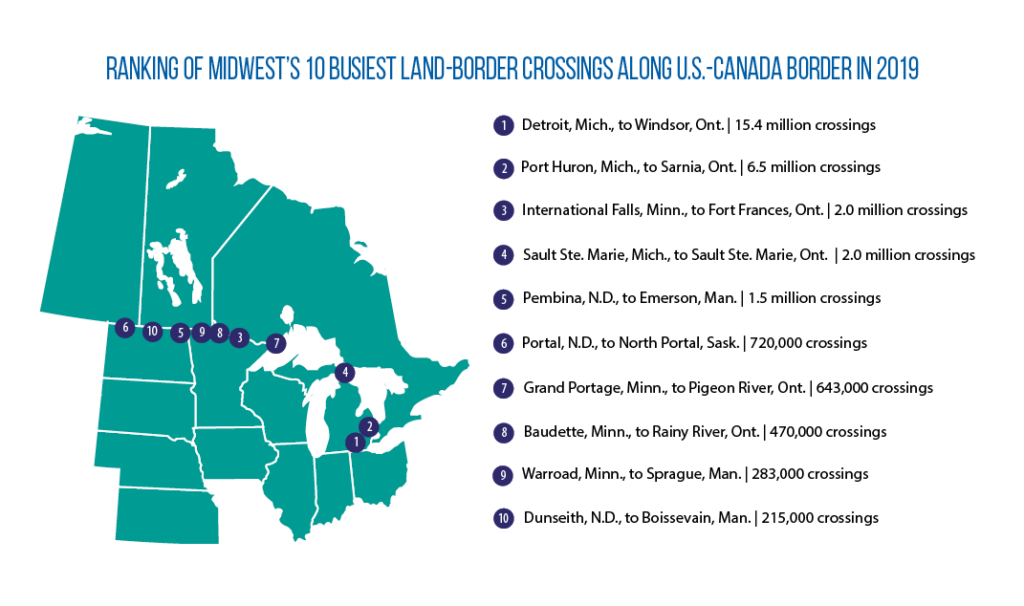

The amount of commercial traffic (the movement of trucks and trains) fell at the border, but not as precipitously as some initially feared: In 2020, binational commercial traffic was down 12.8 percent in Detroit and 7.3 percent in North Dakota’s border-crossing town of Pembina compared to the previous year.

“The ability for that commercial traffic to continue across the border was really remarkable,” Goertzen says. “I think that we need to take a moment to recognize that as really important and significant.”

Additionally, at least some of the downturn in binational commercial activity had nothing to do with the border, but rather with larger supply-and-demand interruptions related to the pandemic.

On the other hand, non-commercial traffic (personal vehicles, buses and pedestrians) was way down in 2020 — compared to the prior year, 72 percent fewer people traveled between Detroit and Windsor and 81 percent fewer people crossed at Sault Ste. Marie.

This downward trend continued well into 2021, even with the availability of COVID-19 vaccines.

Goertzen believes it took too long to reopen the border for non-commercial traffic, causing unnecessary hardships for communities across the region.

“We need to prioritize that and realize that the relationship is more than just commercial. It is social as well,” he says.

Cars approach the Port Huron-Sarnia border, one of the busiest crossings in the Midwest.

States, provinces helped constituents handle closure

When the border was only open for commercial activity and other “essential” traffic, state and provincial leaders intervened to assist communities and individuals.

In April, North Dakota Gov. Doug Burgum, then-Manitoba Premier Brian Pallister and Saskatchewan Premier Scott Moe announced the Essential Worker Cross-Border Vaccination Initiative. This first-of-its kind program allowed truckers from Manitoba and Saskatchewan to receive authorized vaccines at North Dakota highway rest stops a few miles from the border.

On the eastern end of the Midwest, efforts centered on ensuring that some of the most important workers in the fight against COVID-19 could continue their jobs. As just one example, Henry Ford Healthcare in Detroit had 950 Canadian employees as of March 2020.

“There are always challenges getting [these workers] in and out of Ontario and into Michigan,” says Earl Provost, Ontario’s Agent-General in Chicago.

“The Ontario government worked closely with the [Canadian] federal government, which worked with the U.S. administrations to make certain that the flow of essential workers wasn’t too adversely affected.”

Not only have health care providers and workers come to rely on having cross-border access, so too have their patients. Under a provincial agreement with Altru Health System, some Manitoba residents can access services at facilities in the Minnesota towns of Roseau and Warroad.

“It is a lot closer to get health care services in Roseau, for example, than it is to drive to the next health care center in Manitoba,” Goertzen says.

Could this arrangement continue under a closed border?

The Manitoba government made sure it did, working closely with the national governments to ensure that access would not be interrupted.

According to Goertzen, the work of states and provinces was essential to navigating through many issues related to the border closure, a lesson on how both countries can respond to future disruptions.

“The subnational level can do things and come up with arrangements more quickly than at the national level,” he adds.

“Maybe in the future we need to rely more on that subnational discussion and problem-solving, and then bring along the national governments a little bit later.”

Border reopening delayed too long for some

When the March 2020 border closure was announced, Canadian and U.S. officials said they would reconsider the policy every 30 days or so, which they did.

For well over a year, the restrictions on non-essential travel were revisited regularly, but remained unchanged.

The first easing of the land-border closure came on July 5, 2021, when Canadian citizens and permanent Canadian residents coming from the United States were allowed to enter Canada without having to quarantine afterward.

Notably, this reopening pertained only to the land border. Cross-border travel by air, in fact, had already been permitted for months. However, this air-travel option was not necessarily the best one for many people, considering that 90 percent of Canadians live within 100 miles of the United States.

According to Greenwood, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) likely allowed more-relaxed rules on cross-border air travel for a few reasons. One, the CBP had advanced notification on who was coming and going. Two, it had a private-sector intermediary (the airlines) determining whether a traveler was vaccinated and had a negative COVID test.

But Greenwood believes advanced screening and a vaccine-verification process for land-border crossings were possible as well. Such policies may have helped reopen the border more quickly for non-commercial traffic.

As vaccine rates rose, pressure on both governments to reopen the land border mounted.

In July, during the 75th Annual Meeting of The Council of State Governments’ Midwestern Legislative Conference, members of the MLC (state and provincial legislators) passed a resolution supporting a full border reopening for vaccinated individuals. Delivered to federal leaders in Washington, D.C., and Ottawa, the resolution pointed out that the strong economic and social relationship between the two countries is “based on the efficient movement of people, goods and services.”

One week after the MLC passed this resolution, Canada announced that fully vaccinated citizens and permanent residents of the United States would soon be permitted to enter Canada. Additionally, unvaccinated minors younger than 12 could enter the country if they were accompanied by a fully vaccinated parent or guardian.

In the first week after Canada reopened its border, around 219,000 non-commercial crossings were made by Americans. This big influx of travel caused some hefty wait times, including a seven-hour wait at the International Falls (Minnesota)-Fort Frances (Ontario) crossing.

Many expected Canada’s announcement to be followed in short order with an announcement that the United States would open its border to fully vaccinated Canadian travelers. After all, the two countries had closed the border bilaterally and in unison in March 2020.

However, this did not happen. The United States extended its land-border closure three more times.

At different points during the border closure, members of the U.S. Congress expressed dismay. In January 2021, 24 U.S. representatives urged the Biden administration to reopen the border. In September, eight U.S. senators did the same.

On Oct. 12, the Biden administration told members of Congress that the U.S. side of the Canadian border would open to vaccinated Canadians in early November.

During the first phase, fully vaccinated Canadians are able to travel across the land border for non-essential reasons such as tourism and family visits. Initially, there is no testing requirement for Canadians entering the United States. The second phase will begin in January, at which point all travelers, including truck drivers and other essential workers, must be vaccinated.

Pandemic underscored value of binational relationship

According to Provost, cross-border supply chains (a hallmark of the U.S.-Canada relationship that has the two countries’ businesses and workers making things together) proved to be resilient.

“Now you’re seeing an uptick in traditional manufacturing in Ontario, Indiana, Ohio and Michigan,” he adds.

However, vulnerabilities in the supply chain and manufacturing have been exposed — for instance, shortages in medical equipment at the height of the pandemic and an inadequate production of semiconductor chips (since 1990, the U.S. share of global production of semiconductors has slipped from 37 percent to 12 percent).

One lesson from the pandemic is that the resiliency of a nation’s supply chain depends on the reliability of its trading partners. At this summer’s MLC Annual Meeting, two experts on trade and the economy urged legislators to embrace the concept of “ally shoring.” First, identify products and economic sectors where domestic manufacturing is needed to protect national security and provide good-paying jobs. Next, develop secure supply chains for these products with countries that share democratic values and are committed to rules-based trade.

For the United States and Canada, this would mean deepening their economic relationship, including making more essential goods together through the cross-border supply chain.

Meanwhile, with the border open again, other aspects of the binational relationship can return to normal, especially for people living close to the border. Trips to see friends and family, or go to a favorite restaurant or store, are once again only a short drive away — even if they are traveling to another country.

U.S.-Canada Trade in the Midwest

Trends in # of Commercial Border Crossings at Select Entry Points in Midwest

| Crossing | 2019 (full year) | 2020 (full year) | % change | 2021 (January-June) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Detroit | 3,243,335 | 2,828,059 | -12.8% | 1,462,067 |

| Port Huron, Mich. | 2,037,199 | 1,827,763 | -10.3% | 1,026,745 |

| International Falls, Minn. | 885,058 | 836,054 | -5.5% | 387,955 |

| Pembina, N.D. | 611,147 | 566,824 | -7.3% | 314,286 |

| Portal, N.D. | 494,092 | 477,446 | -3.4% | 244,960 |

| Sault Ste. Marie, Mich. | 117,815 | 114,924 | -2.5% | 60,282 |

Trends in # of Non-Commercial Border Crossings at Select Entry Points in Midwest

| Crossing | 2019 (full year) | 2020 (full year) | % change | 2021 (January-July) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Detroit | 12,140,742 | 3,354,947 | -73.0% | 1,025,674 |

| Port Huron, Mich. | 4,512,692 | 804,277 | -82.2% | 106,780 |

| Sault Ste. Marie, Mich. | 1,856,105 | 359,091 | -80.7% | 42,219 |

| International Fall, Minn. | 1,107,245 | 202,306 | -81.7% | 26,226 |

| Pembina, N.D. | 858,117 | 153,837 | -82.1% | 25,077 |

| Grand Portage, Minn. | 617,599 | 94,737 | -84.7% | 5,135 |

Binational Trade in Midwest: $ Value of Merchandise Imports and Exports in 2019 (Canadian $)*

Sources: Statistics Canada and Government of Canada

| State | Alberta | Manitoba | Ontario | Saskatchewan | Top good exported to Canada* | Top good imported from Canada* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illinois | $41.4 billion | $3.5 billion | $19.9 billion | $2.6 billion | Fuel oil | Crude petroleum |

| Indiana | $546 million | $1.3 billion | $21.5 billion | $1.4 billion | Trucks | Pharmaceutical products |

| Iowa | $806 million | $1.4 billion | $3.7 billion | $1.1 billion | Animal feed and food industry residues | Aluminum |

| Kansas | $478 million | $291 million | $2.3 billion | $245 million | Automobiles | Aircraft and parts |

| Michigan | $4.8 billion | $512 million | $81.8 billion | $283 million | Trucks | Automobiles |

| Minnesota | $6.8 billion | $3.0 billion | $5.3 billion | $3.8 billion | Fuel oil | Crude petroleum |

| Nebraska | $195 million | $535 million | $1.7 billion | $389 million | Farm machinery | Animal feed and food industry residues |

| North Dakota | $3.9 billion | $1.5 billion | $2.8 billion | $1.5 billion | Fuel oil | Oil seeds |

| Ohio | $2.1 billion | $1.3 billion | $30.8 billion | $943 million | Motor vehicle parts | Motor vehicle parts |

| South Dakota | $187 million | $292 million | $378 million | $161 million | Animal feed and food industry residues | Fertilizers |

| Wisconsin | $1.4 billion | $1.8 billion | $8.7 billion | $832 million | Paper and paperboard | Plastics |