MLC Chair’s Initiative | 2021

Farm practices can help states meet larger carbon-reduction goals

Talk of addressing climate change typically begins with a state’s energy and transportation sectors. It shouldn’t end there, says Jimmy Daukas, a senior program officer at the American Farmland Trust, a national, nonprofit group that focuses on protecting agricultural land and advancing environmentally sound practices on it.

“One of the challenges is to get all of that land, and our forestry land, into the discussion,” he adds. If that happens, he and other proponents of farm-based conservation believe the result will be new policies that open economic opportunities for producers while reducing states’ carbon footprints.

That’s already begun to occur, in fact, albeit via state initiatives often with other conservation goals in mind.

Take Minnesota’s Agricultural Water Quality Certification Program as an example. Launched statewide in 2016, the program enrolled 1,038 farms totaling 734,000 acres in its first five years. The state offers technical and financial assistance to producers who adopt evidence-based practices to prevent nonpoint water pollution. Minnesota not only has tracked the impact of these practices on water quality and farm profitability (positive on both fronts), but on the state’s carbon footprint.

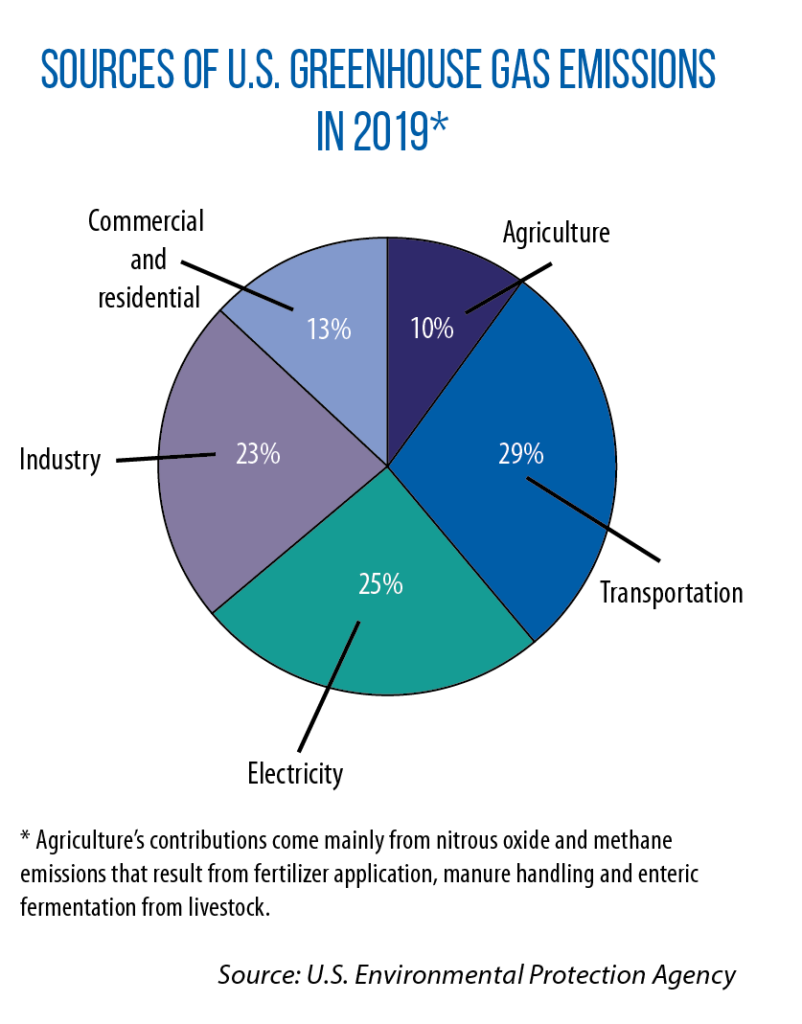

The results: A reduction in greenhouse gas emissions equivalent to 100 million fewer miles being driven by an average passenger vehicle. That’s because a sound nutrient management plan decreases a farm operation’s nitrous oxide and methane emissions. Likewise, when an agriculture producer begins using cover crops or conservation tillage, more carbon is sequestered in the soil.

“One of the exciting things about soil health is that it’s a win-win,” says Bianca Moebius-Clune, climate initiative director for the American Farmland Trust. Investments in soil health and water quality already are commonplace in the Midwest, and the American Farmland Trust points to strategies being tried in states such as Illinois and Iowa, where farmers who plant cover crops get a $5-an-acre reduction in crop insurance premiums.

Daukas says the next step is to create new programs with a stated goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions and sequestering carbon on farmland. “What we don’t want to have happen is for states to say, ‘We have a water quality program and it does climate, so we don’t need anything else,’ “ he says.

In Wisconsin, the Governor’s Task Force on Climate Change has proposed paying “carbon farmers” for their regenerative agricultural practices. Gov. Tony Evers included this idea in his budget, calling for up to $25,000 of grants and technical assistance per recipient. It did not end up in the Legislature’s final budget agreement.

At the federal level, action on climate change became a part of the last farm bill thanks to programs targeting soil health. A more explicit, climate-focused conservation policy is part of the proposed Build Back Better legislation being negotiated in the U.S. Congress. It calls for a total of $28 billion going to various agricultural initiatives that reduce greenhouse gas emissions — for example, $5 billion alone to increase the use of cover crops.

Other opportunities emerging for the Midwest’s farmers include participating in carbon offset markets and contributing to new, private sector-led sustainability goals.

“More and more major food companies are beginning to set climate targets within their supply chains,” Rod Snyder, president of Field to Market: The Alliance for Shared Agriculture, said to legislators during a session of this year’s CSG Midwestern Legislative Conference Annual Meeting. “If you look at many of the corporate initiatives, they often start within their own four walls or their transportation fleet. … “But they’ve now begun to look even further to say, ‘How can we partner with farmers?’ “

South Dakota Senate Majority Leader Gary Cammack has chosen agriculture conservation as the focus of his Midwestern Legislative Conference Chair’s Initiative for 2021.