Police in the schools: States play central role in the funding and training of resource officers

Last November, a teenage gunman opened fire at Oxford High School in Michigan, killing four students. According to local news sources, an on-campus school resource officer (SRO) played a key role in ending the tragedy.

Michigan Rep. Gary Howell, too, credits the SRO for preventing further losses of life at the school, where his own son works as a teacher.

Two days after the shooting, Howell took legislative action: a proposal to increase state support for schools seeking to employ SROs. As originally written, HB 5522 would have provided $10 million in grants, via a mix of state and federal dollars. Howell’s amendment — included in a House-passed version of HB 5522 — hiked that total to $50 million.

“There are some districts that, for whatever reason, prefer not to have police officers in the schools,” he says.

But for districts wanting SROs in their schools, Howell does not want a lack of financial resources standing in the way.

Across the country, the presence of SROs in schools has become more common in recent decades. Some researchers credit the rise to high profile incidents like the 1999 Columbine shooting and the allocation of federal grant opportunities, like those distributed by the Department of Justice’s Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS) office.

However, this approach to school safety also has been under increased scrutiny, particularly following the police killing of George Floyd.

In the Midwest, some of the largest school districts have dramatically reduced, if not outright eliminated, the use of SROs.

In Des Moines, Iowa, this decision was made in part based on feedback from town hall events and survey responses.

District leaders also had found that Black students were twice as likely to receive referrals to the principal’s office compared to White students, and were arrested at a rate of six times their White classmates.

“What we have seen is that we overused the law enforcement when they [were] on campus,” says Jake Troja, an administrator in the Des Moines school district.

“In all cases, law enforcement are invited into the situation by the schools. The disproportionality that occurred, is that the responsibility of the school? I think that’s why we evaluated that program and wanted to make some changes.”

Another factor in shifting away from SROs, Troja adds, was an evaluation of the return from investing in these officers. “Looking at data, we saw that almost always our staff members were the first folks involved [in responding to student-misbehavior incidents],” he says.

While there was an initial increase in fights shortly after the shift away from SROs — a phenomenon he blames in part on the disruptions on behavior management caused by the COVID-19 pandemic — Troja says student arrests and disproportionalities have decreased.

Recent national studies have examined the roles and impacts of SROs as well.

In 2021, researchers from the RAND Corp. and State University of New York-Albany — using a sample of over 80,000 schools across the country and cross-sectional student data reported between 2014 and 2018 — found that SROs reduce the number of in-school fights, but don’t make a statistically significant difference in preventing other incidents such as school shootings.

Their study, “The Thin Blue Line in Schools: New Evidence on School-Based Policing Across the U.S.,” also concluded that the presence of SROs can increase schools’ use of suspensions, expulsions and arrests, all of which disproportionately affect students who are Black, are male or who have a disability.

‘Proactive’ and ‘versatile’

D.J. Schoeff, president of the National Association of School Resource Officers, says some of the data on SROs doesn’t necessarily reflect their true impact in schools — including the number of serious incidents preemptively thwarted by SROs, whether SROs received specialized training, or that one explanation for increased student offenses in schools with SROs is greater detection. The point about greater detection was even acknowledged in the “Thin Blue Line” report.

During the school shooting at Oxford High School, Howell says, the quick response time of an on-campus SRO proved to be invaluable.

According to Schoeff, who is a police sergeant in the Indianapolis suburb of Carmel, the job of an SRO is to foster safe school environments through supportive student interactions.

“Our role is proactive. … We’re about being a positive adult influence in the lives of kids who need [it],” he says.

“It is a very versatile position,” he adds. “You have to understand the teen brain, you have to understand special education.”

The National Association of School Resource Officers offers its members a 40-hour training course on those topics, as well as on de-escalation tactics, cultural awareness, and how to effectively address behavioral problems in adolescents.

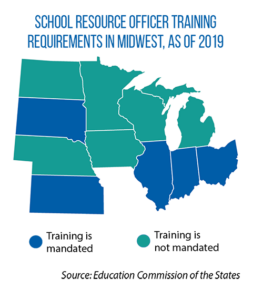

As of 2019, five states in the Midwest required SROs to take part in training of some kind (see map). Early in 2022, Indiana lawmakers were advancing a bill (HB 1093) to tighten statutory language defining SROs and related training requirements.

Rep. Howell says he supports training SROs on adolescent behavior, but cautions that some smaller communities in Michigan may not have the capacity to devote a single officer to work in schools.

“Some of these [officers] may end up being very part-time people, and if you’re in a small town with, say, a three- or four-person police force, it’s harder to specialize,” Howell says.

Update: Almost two months after the interview with Des Moines Public Schools was held, a deadly shooting took place outside of, but still on the campus of, East High School in Des Moines on March 7, 2022. As of the date of this article being published, three teenagers were confirmed to have been shot, one fatally, in a drive-by shooting. The teenager who lost his life was not a student at the school.