Giving new life to recycling policy

State proposals include setting new recycling goals in statute, adding plastics to ‘extended producer responsibility’ laws, and investing in new markets for reused products

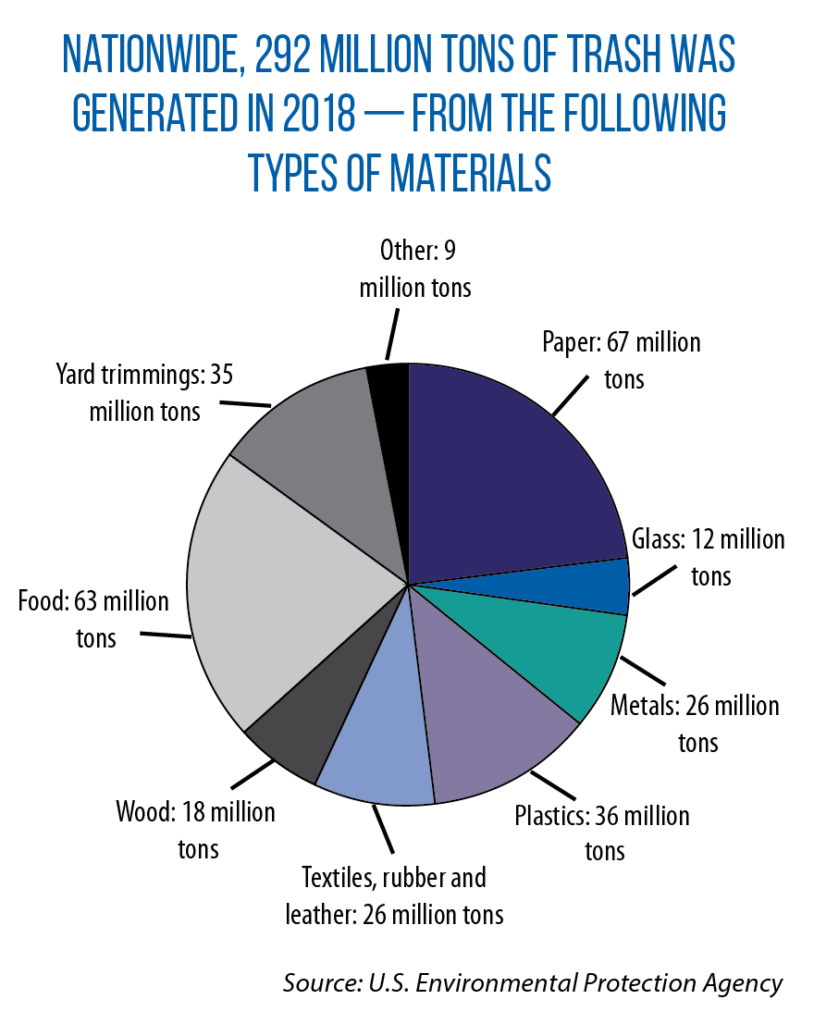

Over the course of a year, the United States generates close to 300 million tons of municipal solid waste — everything from paper, glass and plastics, to food, yard trimmings, metals and aluminum. It is the equivalent of 4.9 pounds of waste per person, per day.

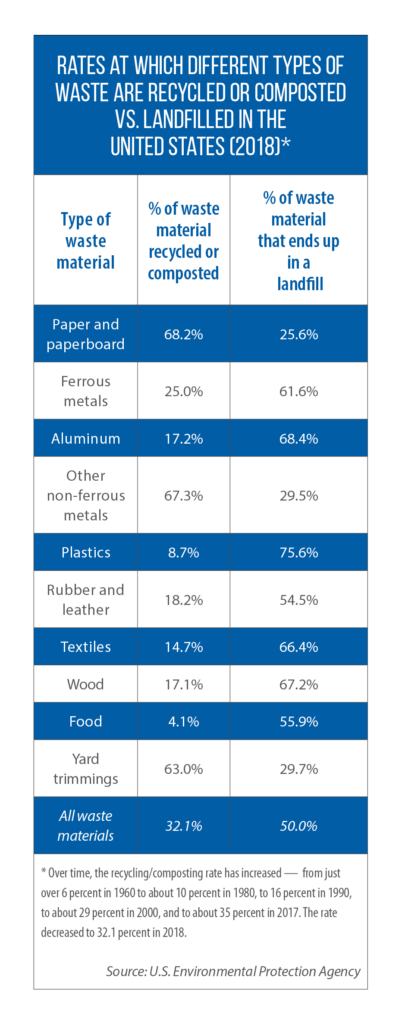

About half of this waste ends up in landfills, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, compared to a little more than a quarter of it being recycled. And recycling rates for different materials can vary widely.

little more than a quarter of it being recycled. And recycling rates for different materials can vary widely.

Paper and paperboard? Comparably high rates.

Plastics, textiles and aluminum? Much lower (see table).

Recycling conserves natural resources, saves energy and strengthens American manufacturing. A survey by The Recycling Partnership found that 85 percent of Americans strongly support recycling, and a majority increasingly prefer sustainable products and are willing to pay more for them.

However, many obstacles (some long-standing, some newer) stand in the way of getting recycling rates up in states across the country — “confusion about what materials can be recycled, [a] recycling infrastructure that has not kept pace with today’s diverse and changing waste stream, reduced markets for recycled materials, and varying methodologies to measure recycling system performance,” according to the U.S. EPA’s latest National Recycling Strategy.

One way to address these challenges, and move in the direction of more recycling and less landfilling, is state policy.

“We have an embarrassingly low recycling rate,” Michigan Rep. Gary Howell, chair of the state House Natural Resources and Outdoor Recreation Committee, says about his home state. “We are the state that exemplifies clean water, and the last thing we want to do is encourage more landfilling.”

Yet he worries that Michigan has been doing just that, as evidenced not only by the state’s recycling performance but by it being home to other jurisdictions’ trash.

“Twenty-five percent of garbage landfilled comes from out of state, the vast majority from Canada,” Howell says.

He is part of an ongoing legislative effort in Michigan to jump-start the use of recycling, composting and other alternatives to landfills.

the use of recycling, composting and other alternatives to landfills.

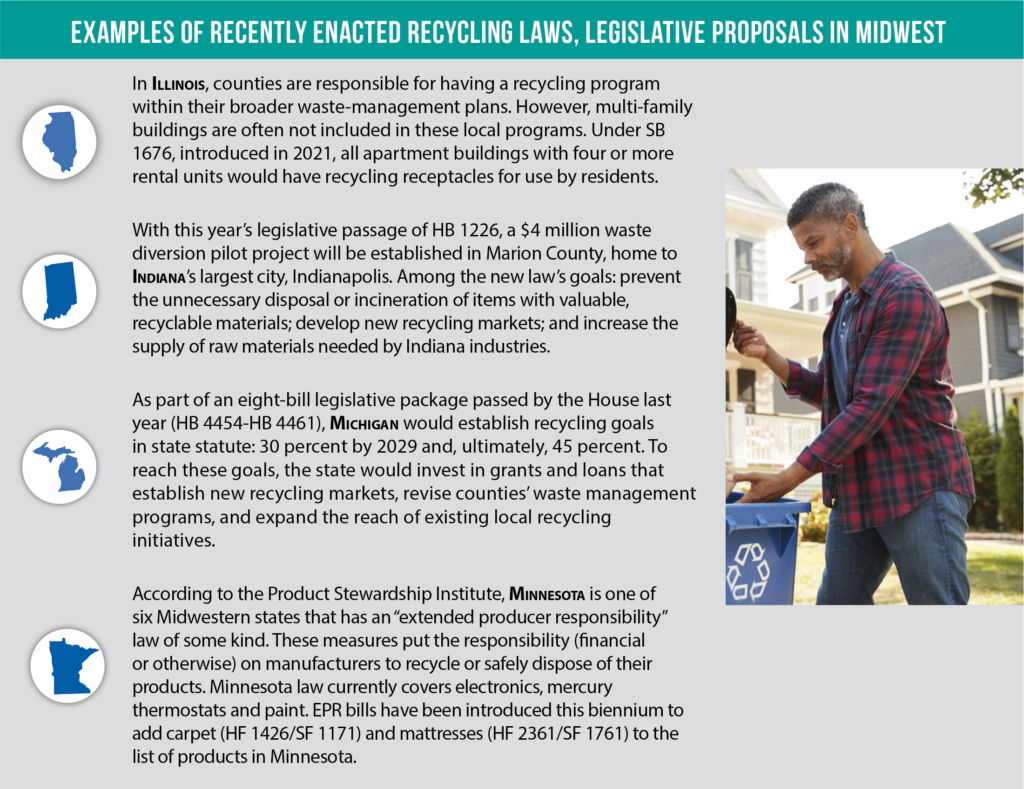

Recent bills and new laws in other Midwestern states reflect similar goals. Outside the region, some legislatures have passed first-in-the nation measures related to plastics, expanded producer responsibility and recycled content. Here is an overview of the “state of recycling” and what may lie ahead, starting with recent activity in Michigan.

‘Landfills should be the fallback’

In Michigan, in-state estimates have placed its recycling rate at about 18 percent. A bipartisan package of bills (passed by the House last year, not yet acted on in the Senate) sets a goal of getting that rate to 30 percent by 2029 and, ultimately, to 45 percent.

To get there, HB 4454-HB 4461 call for a series of new actions:

- state assistance for Michigan counties to rewrite their waste management plans and standards in a way that increases recycling and composting in local communities;

- an expansion of residential recycling services;

- an update of state requirements for landfill, recycling and composting facilities; and

- the use of money in Michigan’s Solid Waste Management Fund (supported by fees leveled on landfills, composting and waste processing facilities) to develop new recycling markets.

If the bills become law, they would mark a sharp turn in the state’s approach to handling waste, says Kerrin O’Brien, executive director of the Michigan Recycling Coalition.

“The current law is about assuring that every county in Michigan has the capacity to dispose of 100 percent of its waste,” she says. Without any dedicated funding for solid-waste planning, O’Brien adds, counties’ plans are only getting updated when a landfill wants to add capacity.

According to Howell, the legislative package was developed over several years, with input from a broad array of stakeholders — “landfills, municipalities, farm bureaus, manufacturers, anyone who possibly has a connection.”

“We’re taking a broad approach, taking into account recycling and composting,” Howell says. “Landfills should be the fallback.”

Under the House-passed bills, a mix of state grants, loans and other assistance would be used to develop recycling markets, expand local services, and help counties improve their solid-waste plans. This money would come from the Renew Michigan Fund, which was created by the Legislature four years ago (HB 4991 of 2018). A total of $69 million in income tax revenue is deposited into the fund every year, with 22 percent of this money going to materials-management planning, local recycling programs and market development of recyclables.

‘True circularity’ and the impact of state policy’

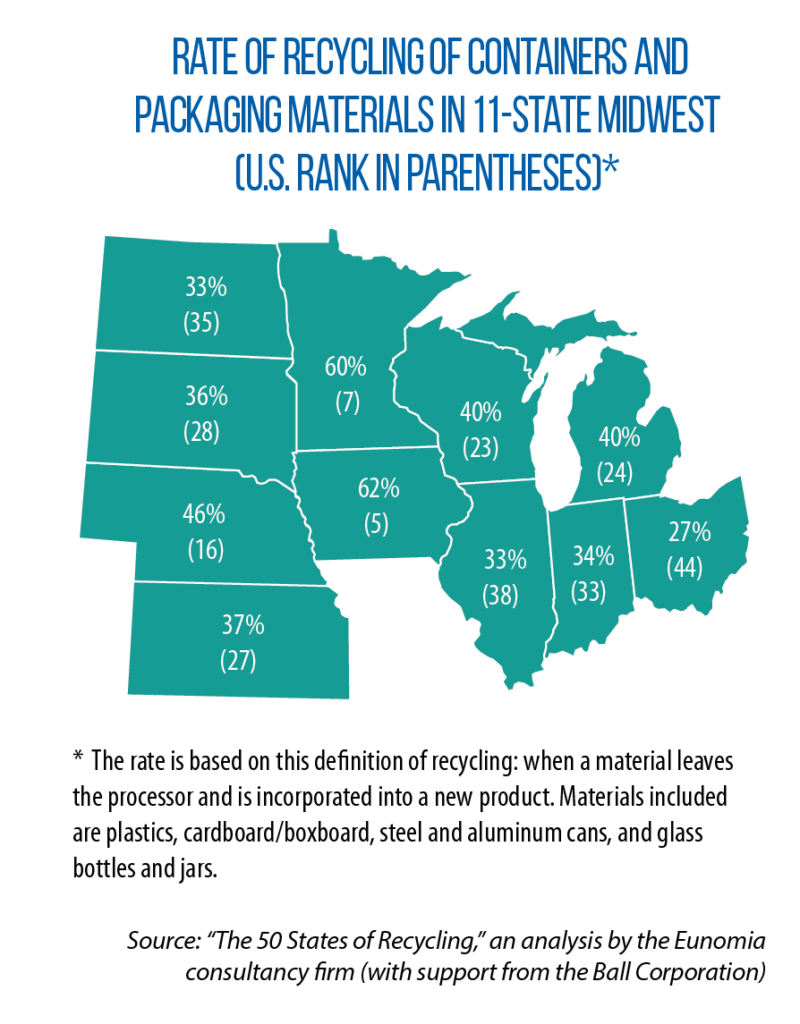

While the U.S. EPA provides an estimated national recycling rate (it is 32 percent), comparisons among states have not been readily available, in part because jurisdictions use varying methods for determining their rates. But earlier this year, Eunomia, an environmental-focused consultancy firm, released what it says is the “first-of-its-kind state-by-state comparable assessment of recycling rates.” (The Ball Corporation, a recycling-based company, provided funding support.)

The study focused on the reuse of common containers and packaging materials. It compared each state using a specific definition/criterion for recycling: when recycled materials are actually incorporated into new products. According to Eunomia, this should be viewed as the “real recycling rate,” as opposed to how many materials are being collected or sorted for recycling. By using the actual material reprocessed into new products as the point of measurement, Eunomia says, the recycling rate is more representative of a material’s true circularity, and accounts for material losses at the sorting and processing stage.

Two Midwestern states, Iowa and Minnesota, rank among the top-performing states (see map). The same study also highlights some of the region’s state recycling policies. For example:

- Wisconsin bans a number of items from landfills and ensures residents have access to curbside recycling programs or to nearby drop-off centers.

- Minnesota sets recycling goals and requirements for local governments, while commercial businesses in that state must recycle at least three types of materials (from a list that includes glass, metal, plastic, paper and food waste). State-level funding and technical assistance help Minnesota’s local governments and businesses meet these goals and requirements.

The Eunomia study notes that across the country, higher state recycling rates often coincide with certain policies: bans on materials entering landfills, higher costs for landfill disposal, data reporting requirements for municipalities, widespread curbside recycling, and the use of deposit return systems, or DRS.

Overview of ‘bottle bills’ in Midwest

The most familiar type of DRS is a “bottle bill,” a state law that requires refundable deposits on certain beverage containers.

Iowa and Michigan are among the 10 U.S. states with such laws in place. (Every Canadian province has a bottle bill as well.)

About the Iowa law

Iowa’s bottle bill was enacted in 1978 as a litter-reduction measure. Consumers are charged 5 cents for each carbonated and alcoholic beverage that is sold in glass, plastic or metal bottles or cans. They receive a 5-cent refund when returning the container to a store or redemption center.

Participating retailers and redemption centers receive that amount back, plus an extra cent as a handling fee, from the distributors who pick up the recyclables. The recycling rate in Iowa of these containers is currently around 71 percent, substantially higher than the national average.

Efforts have been made over the years to change Iowa’s law to increase the list of containers eligible for redemption. For example, non-carbonated water and sports drinks are not covered, though they now make up over half of the beverage container purchases in the state. Those efforts have not been successful. The 1-cent handling fee also hasn’t changed.

But as part of this year’s SF 2378, a bill passed by the Senate in March, the handling fee for redemption centers would increase from 1 cent to 3 cents. Supporters of the bill hope that a payment increase will prop up existing redemption centers and spur the opening of new ones.

Another provision in the bill allows Iowa retailers, such as grocery stores and convenience stores, to opt out of taking back empty bottles and cans beginning in July of 2023.

About the Michigan law

Michigan’s container deposit law also dates back decades, the result of a voter-approved referendum from 1976. That state has an estimated 70 percent return rate for items covered under the law — plastic, metal, glass and paper containers of less than one gallon. (Nationally, according to the Container Recycling Institute, states with bottle bills have a recycling rate for beverage containers of around 60 percent, while non-deposit states only reach about 24 percent.)

In Michigan, 10 cents is added onto each beverage container that consumers purchase in the state; that 10-cent deposit is returned to consumers when they bring back the empty container to a store or redemption center.

Last year, Michigan strengthened enforcement of its bottle bill, including stiffer non-compliance penalties directed at distributors. Also as part of the legislative package (HB 4780-4783), a $1 million fund was created to help local police crack down on illegal activities, such as individuals bringing containers purchased out of state into Michigan to collect bottle returns on beverages that were not subject to the 10-cent deposit.

Proposed legislation in Illinois

In Illinois, Sen. Laura Murphy is eyeing a new approach that would employ a deposit return system along with another state policy lever commonly referred to as “producer responsibility.” Under her proposed legislation, SB 3975, consumers would not have to pay a deposit fee for purchases of beverage containers made out of commonly recycled materials (aluminum, glass or certain plastics).

“We didn’t want to [detract] from what is already working,” says Murphy, noting the existence of many facilities and municipal programs across the state that recycle these materials.

Instead, consumers would pay a deposit fee when purchasing beverage containers not made out of those commonly recycled materials. Also as part of SB 3975, consumers could get a refund on all beverage containers of one gallon or under, regardless of whether they paid a deposit fee or not.

How would they get the refund?

That is where the “producer responsibility” part of SB 3975 comes in. Beverage distributors and importers would be required to be part of a nonprofit “producer responsibility organization” that establishes and maintains redemption centers for consumers — for example, the installation of reverse vending machines and use of drop-off sites at retail locations.

‘Producer responsibility’ laws and plastics

This idea of “producer responsibility” is not new. Currently in the United States, there are close to 100 state laws, covering 17 different products, that meet the definition of “extended producer responsibility,” or EPR, according to the Product Stewardship Institute.

With an EPR law, states place the responsibility of treating, recycling and/or disposing of certain consumer products on producers, manufacturers and retailers (often through the creation of producer responsibility organizations, as envisioned in Illinois’ SB 3975).

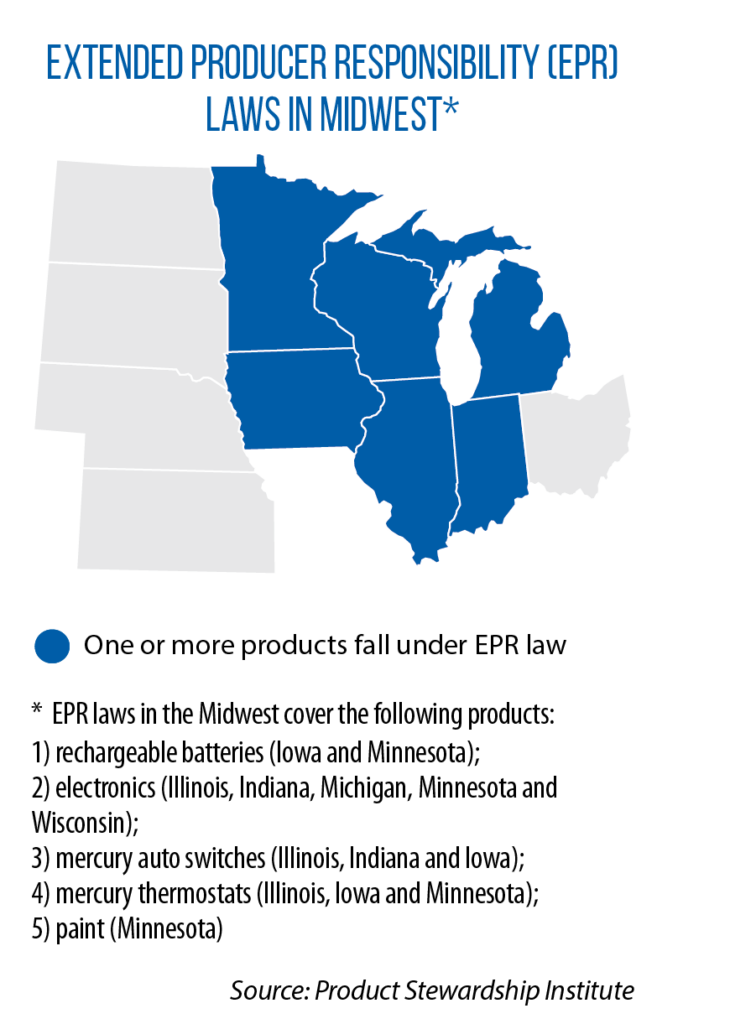

In this region, six states — Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota and Wisconsin — have a total of 14 EPR laws that cover electronics products, rechargeable batteries, paint, mercury auto switches and/or mercury thermostats (see map). This year, bills introduced in Illinois and Minnesota would make producers responsible for the life cycle of a variety of other products: carpets, mattresses, paint, pharmaceuticals, solar panels and wind turbine blades.

“We use a method that starts with a basic model, and we work with each state to figure out what the state wants, then we bring in other stakeholders, including environmental groups, producers, etc.,” Scott Cassel, CEO of the Product Stewardship Institute, says about its work on EPR measures in various U.S. states.

“There is always producer-funding [requirements included in the legislation], but the question is, how much will end up in the law? There is always some degree of producer management, and the question again is, how much gets incorporated into the law?”

Last year, Maine became the first U.S. state with an EPR law that covers plastics and packaging materials (LD 1541); Oregon soon followed. In Maine, producers of these products will pay into a fund that aims to increase the recycling of packaging materials by:

- reimbursing municipalities for recycling and waste-management costs,

- making new investments in the state’s recycling infrastructure, and

- raising awareness among residents about how to recycle.

Maine’s program will be operated by a stewardship organization (selected by the state Department of Environmental Protection). Costs to fund this stewardship organization, as well as state oversight, will be funded through mandatory producer payments.

Oregon’s Plastic Pollution and Recycling Modernization Act (SB 582) requires the producers of plastic packaging, paper and food service ware to join producer responsibility organizations. These PROs will charge annual membership fees based on the environmental impacts of each product covered under the law.

Oregon will establish a collection list to standardize recycled items across the state, and funding will go toward upgrading facilities to meet new performance standards. These facilities will be required to obtain a state permit in order to receive recyclable materials from various communities. The PROs, meanwhile, must help raise awareness about the state’s recycling initiatives.

A notable part of both these states’ new EPR laws is the inclusion of plastics. According to the U.S. EPA, in 2018 (the latest figures available), plastics were the second-largest item in landfills, comprising 18.5 percent of landfill tonnage, behind only food waste, at 24 percent.

And less than 9 percent of plastics are recycled, with more than 75 percent landfilled. The presence of plastics in the waste stream is particularly worrisome because they never decompose: Plastics break into smaller and smaller pieces, which can seep into water treatment plants and into tap water, and be eaten by fish and other wildlife that mistake them for food.

No Midwestern state has EPR laws similar to Oregon’s or Maine’s, though this year in Illinois, two bills were introduced (HB 4258 and SB 3953) to make the producers of most packaging responsible for the end life of their products.

Consumers, companies alike embrace recycling

Another policy option: require products to have a certain amount of recycled content. The states of Washington (SB 5022) and Connecticut (SB 928) passed such laws last year.

Even without such policies in place, some manufacturers have intentionally “designed for recycling.” This means not only including recycled content, but also making products easier to recycle at the end of life.

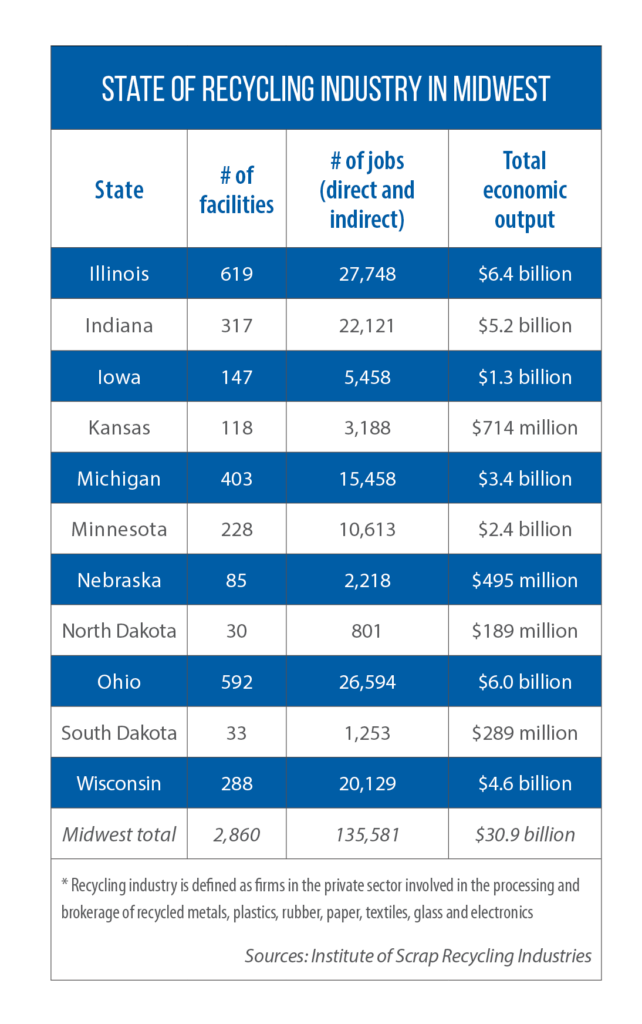

For more than 30 years, the Institute of Scrap Recycling Industries has given an annual award to companies that “design for recycling.” And Danielle Waterfield, chief policy officer for the institute, says the idea is gaining greater traction.

“It is critical that manufacturers incorporate this ‘design for recycling’ in their products,” she adds.

Meanwhile, more brand companies are making global commitments to move toward making their packaging out of recycled content, says Scott Mouw, senior director of strategy and research with The Recycling Partnership.

Polls show that vast majority of consumers want to recycle, too. But Mouw notes that only 40 percent of U.S. households have “equitable access to recycling,” meaning they can recycle an item as easily as throwing it away.

State policy is one mechanism for changing numbers like this.