One federal aid application holds key to college financial aid; states try to get more students to complete it

Even as a longtime member of the Indiana Senate Education Committee, Jean Leising discovered a few years ago that she had a lot to learn about the value of filling out a Free Application for Federal Student Aid. The lesson came from her oldest granddaughter, who was nearing college age at the time.

“When her mom told me they were going to fill out the FAFSA, I said, ‘Oh, you guys won’t qualify for anything because you and your husband both work [and make a decent living],’ ” Leising recalls.

As it turns out, completing the application opened a world of financial assistance — a Presidential Scholarship to attend Purdue University, and another scholarship because of her granddaughter’s involvement in 4-H.

“After that experience, my thought was, What can I do about this as a legislator?” Leising says. “Because I knew there were probably a whole lot of my constituents that also didn’t know about how important [FAFSA completion] can be.”

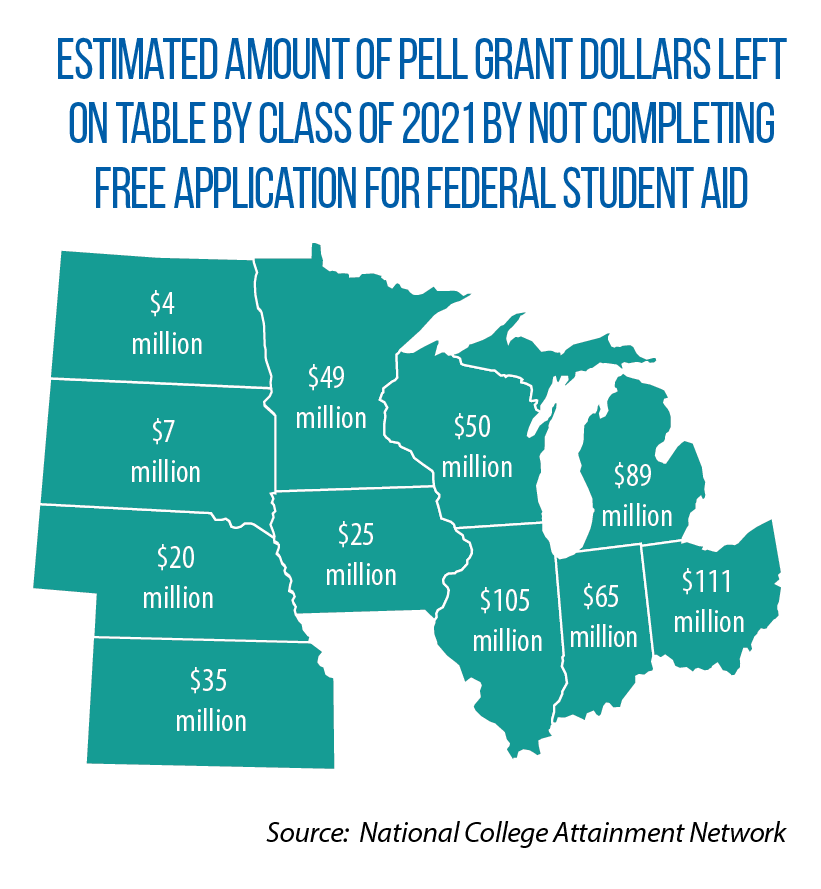

For Indiana’s high school class of 2021, a total of $65 million in federal Pell Grants was left on the table due to a lack of FAFSA completion, according to the National College Attainment Network.

In recent years, Leising has sponsored various FAFSA-related bills, including a proposal from 2021 to provide monetary incentives for school districts to boost completion rates (SB 54) and legislation from 2022 (SB 223) that would have made FAFSA completion a high school graduation requirement (with opt-out provisions for students and their families).

Neither of those measures passed, though this year’s SB 82 was signed into law. It requires high schools to share FAFSA information prepared by the Indiana Commission for Higher Education with high school seniors.

According to Leising, much of the opposition to her “universal FAFSA” proposal — tying high school graduation to the completion of an application — came from local education groups.

Minus this kind of requirement, states have other options for increasing the number of students completing the FAFSA, says Bill DeBaun, senior director of data and strategic initiatives for the National College Attainment Network. One common approach is data sharing: states get information on which students have or have not completed a FAFSA and make it available to schools.

School- and district-wide data also can be used to create friendly competitions — for example, “FAFSA completion challenges” in states such as Kansas and Michigan.

Two years ago, Minnesota legislators directed the state’s Office of Higher Education to set a statewide FAFSA goal. The office is now working to increase FAFSA filings by 5 percentage points every year for five years. (The state’s completion rate was 48 percent for the class of 2021.)

In Ohio, state grants are awarded to groups that promote FAFSA completion, and a new law (part of the state budget, HB 110) requires schools to work with the Department of Higher Education on data sharing.

Another way to boost rates: make eligibility for state financial aid contingent on FAFSA completion. Illinois does so through its Monetary Award Program. That state also is currently the only one in the Midwest that ties high school graduation to filing a FAFSA. For these “universal” laws to be workable, DeBaun says, states must include “robust opt-out” provisions, and also make sure that schools have enough lead time and resources (including access to student-level data) to implement the requirement.