Leadership, including from legislators, is needed to launch mental health courts — and make them work

For many justice-involved people struggling with their mental health, incarceration is not conducive for recovery.

“[It] disconnects [offenders] from whatever care they did have in the community, their Medicaid might be terminated, and we see rates of homelessness among people who’ve been incarcerated are seven times [higher than] the rate of people who have not,” Megan Quattlebaum, director of The Council of State Governments Justice Center, said during a session at the Midwestern Legislative Conference Annual Meeting.

Often at the local level, a lack of resources limits the availability of mental health services in county jails. In state prisons, much of the programming works best for offenders with long sentences.

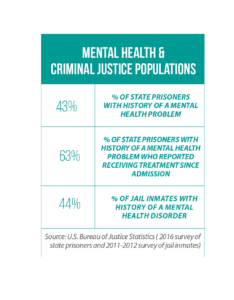

And the number of people in need of treatment is notable.

According to a study released in 2021 by the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics: 43 percent of state prisoners had some history of a mental health problem.

One option for states: Invest in and expand the reach of mental health courts.

In lieu of incarceration, these dockets allow judges to compel offenders to attend psychiatric therapy, develop behavioral change plans with case workers, or pursue other treatments.

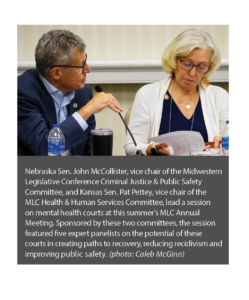

Along with Quattlebaum, four other experts took part in the MLC session’s panel discussion, sharing their experiences with mental health alternatives and answering questions from legislators.

For these mental health courts to work, former Ohio Supreme Court justice Evelyn Stratton said, they need a “champion” — whether it be a legislator, a judge, a medical professional or someone else who rallies stakeholders and identifies funding resources.

During her tenure on the bench, Stratton helped create the Ohio Supreme Court’s Advisory Committee on Mental Illness & the Courts (now a task force run by the attorney general).

“The [CSG Justice Center] helped us get some grant monies that we [used to get] 10 states to do a statewide supreme court committee to push mental health courts,” Stratton told lawmakers.

That was one recurring message to legislators during the session: Outside resources are available to local communities and states looking to expand the reach of criminal justice-based mental health services.

“There are so many free resources and so much free support out there. You do not have to struggle in the dark,” Quattlebaum said. (The CSG Justice Center is among the groups available to help.)

At the federal level, the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration administers the GAINS Center for Behavioral Health and Justice Transformation. Through these centers, state and community leaders are able to access training, launch peer-support services (matching offenders with former patients), and learn how best to connect individuals with local mental health resources.

“You can gather at any municipality level and meet with other municipalities that are working toward establishing mental health courts, or drug courts, or trauma-informed courts,” Kim Nelson, a SAMHSA regional administrator and session panelist, said.

As to the role of state lawmakers in advancing mental health courts, Quattlebaum emphasized the importance of establishing statewide structures — not only securing sufficient appropriations and staff supports, but also establishing standards that are unique from other specialized dockets in a state’s court system.

In Georgia, for example, the Council of Accountability Court Judges sets criteria and best practices for the state’s mental health court operations.

Each of the panelists also stressed that mental health courts are only one piece of the puzzle, and that lawmakers should also prioritize early-intervention strategies that occur long before a person goes before a judge. For example:

- investing in co-responder models that pair behavioral health specialists with law enforcement;

- securing operators for the new national 988 suicide and mental health crisis hotline; and

- supporting local intervention groups and mental health community centers such as the Wichita-based, county-run COMCARE program.