‘Stress tests,’ long-term budget forecasting position states to handle ups and downs of economy

The best of fiscal times may be the ideal period for budget leaders to prepare for the worst, and smart planning means more than building up state rainy day funds and other reserves.

According to Airlie Loiaconi of the Pew Charitable Trusts, two emerging best practices in states stand out: long-term forecasting and budget “stress testing.”

“You already have the building blocks [to implement these practices]; it’s just a matter of bringing them all together,” Loiaconi said during a presentation in July at a meeting of the Midwestern Legislative Conference Fiscal Affairs Committee.

The session was held a few weeks after many states closed the books on a historically strong fiscal year. But legislators during the MLC session also expressed caution about what may soon lie ahead: a slowdown in consumer spending due to inflation and other factors, and a “fiscal cliff” when the additional federal dollars stop flowing to states.

Among the 50 states, Loiaconi singled out Utah as being the “gold standard” in fiscal planning and analysis. Thanks to a mix of statutorily required policies, she said, budget leaders get the information they need to “think long-term and avoid crisis-driven decisions.”

Every three years, for example, the Office of the Legislative Fiscal Analyst evaluates the budget impacts of a moderate recession, a severely adverse downturn and a protracted slump. A five-year time frame is used.

How much revenue should the state expect to lose under these scenarios? How much in contingency funding would be easy to access? How much would be available, but more difficult to access? How does the amount of recession-fueled losses compare to the value of the contingency funds?

These and other questions are addressed in Utah’s budget stress test.

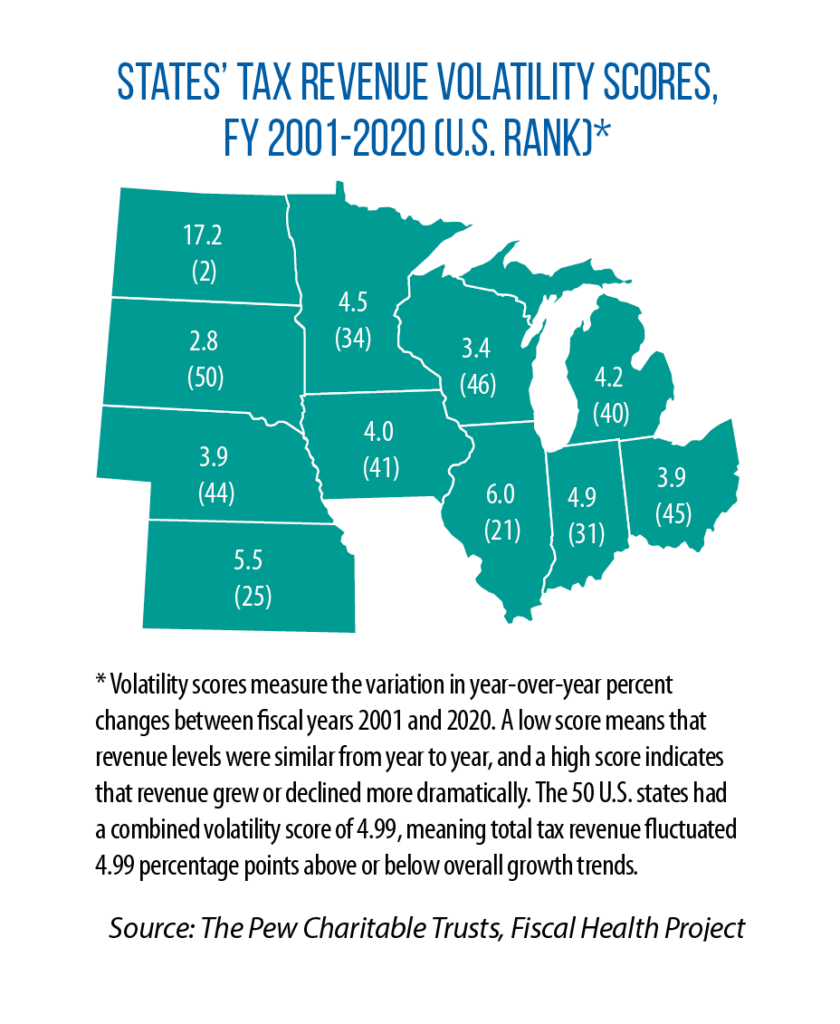

The same office also is directed to produce triennial revenue volatility reports and long-term budget forecasts.

Loiaconi identified several principles for states to follow when implementing these forecasts. They include:

- looking ahead at least three years (Utah’s time frame is five years);

- distinguishing, and perhaps defining in statute, one-time vs. ongoing revenue streams;

- establishing a “current services” baseline that shows how much money will be needed to maintain existing programs in the future;

- accounting for any known policy changes, such as tax cuts or new state programs; and

- identifying any looming structural budget deficits, as well as determining the specific causes.