Changing behaviors of domestic abusers is goal of interventions being used in some state prisons; the search for an effective model continues

For 33 years, October has been recognized as National Domestic Violence Awareness Month.

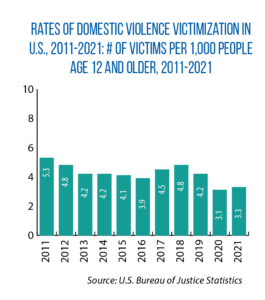

Progress has been made over that time in reducing instances of domestic abuse against women and men. According to the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, in 2003, there were more than 1.48 million known victims of domestic abuse in the country, or 6.2 people for every thousand people ages 12 and older. Last year, that number was around 911,000, or 3.3 people for every thousand.

Despite the positive turn, understanding how to successfully reform abusers has proven to be elusive.

One place where such programming for domestic violence offenders can and often does take place: state correctional facilities.

Can prison-based interventions be effective in reducing recidivism and preventing future, sometimes fatal acts of abuse?

Policymakers, correctional leaders and experts on domestic-violence prevention continue to grapple with this question in many states, including Nebraska and Iowa.

2 tragic deaths in Nebraska

For years, Doug Koebernick, inspector general of the Nebraska Correctional System, has recommended that the state consider reinstating domestic violence intervention programming in prisons.

It has not existed for incarcerated individuals since 2015. In the inspector general’s latest annual report, he noted that department clinicians had recommended domestic violence programming for more than 500 people in Nebraska’s prison system. Without the availability of such programs, interventions occur post-release, or not at all.

The Nebraska Department of Correctional Services has cited at least two reasons for not offering services: a lack of evidence supporting their efficacy, and the availability of more-effective interventions in community settings for parolees.

However, in multiple annual reports, Koebernick has pointed out that parolees’ participation in these community-based programs apply only “if it is a condition of their parole, or [if they are] participating in work release,” and that “people who wait until reaching community corrections to undergo treatment might already have regular access to their domestic partners.”

Such was the case for Hailey Christiansen and Brooke Koch, two Nebraska women murdered by intimate partners who had previously abused them and had been incarcerated. The two women’s stories helped inspire the successful passage this year of the Domestic Abuse Death Review Act (see sidebar article).

Koebernick acknowledges that the model of intervention training previously used in Nebraska prisons — known as the “Duluth Model” — had limited success. National studies, too, have raised questions about the value of this model in preventing future domestic violence.

Nonetheless, Koebernick believes the state should evaluate if non-Duluth models could be useful in Nebraska. One possible alternative already is being employed in a neighboring state.

New intervention in Iowa

In 2010, the Iowa Department of Corrections began a pilot project to assess whether a new intervention model could change the behavior of convicted domestic abusers.

Today, that same model — a revised version of the Achieving Change Through Values-Based Behavior Program, or ACTV — has replaced all previous domestic assault programming. It now operates in multiple prison settings.

Earlier this year, Dr. Amie Zarling, a developer of the ACTV model, published the results of an experimental study examining differences in the outcomes of two sets of Iowa Department of Corrections offenders: those who took ACTV-based intervention classes vs. participants in the Duluth Model.

The 338 men evaluated were all first-time (convicted) domestic abusers; they took part in the programming outside of prison while on probation.

Her study sums up the differences in the two types of interventions this way: “Instead of examining how one’s thoughts about women originated or replacing the thought ‘She shouldn’t treat me this way’ with a more positive or egalitarian thought, [the ACTV model] encourages behaving with respect toward one’s partner even when having that thought.”

That is not to say that the ACTV model teaches participants to suppress feelings of toxic masculinity.

“If a man’s belief that he is superior to women comes up, ACTV addresses that; it just doesn’t automatically assume that is the thing shaping the men’s behavior,” says Zarling, a psychologist and associate professor of human development and family studies at Iowa State University.

She also stresses that the concepts behind the Duluth Model are not wholly wrong or that ACTV is wholly right, but that more empirical research is needed.

Her study showed mixed results.

In terms of participants who acquired a domestic abuse charge one year following their treatment, there was not a significant difference between Iowa’s ACTV and Duluth participants. (Zarling notes the number of transgressors was low and that “it’s really hard to find differences between groups when the outcome measure has such a low base rate.”)

Conversely, data collected from administrative records and female victim reports show that ACTV participants had fewer violent and nonviolent criminal charges and engaged in fewer acts of intimate partner violence after treatment when compared to those in the Duluth group.

“I think this indicates we might be on the right track,” Zarling says. “There have been very, very few successful, randomized controlled trials of domestic violence programming, and I feel very proud of that.”

She adds that subsequent studies and funding for them — such as the grant she received from the federal Office on Violence Against Women — are still needed, as are the resources necessary to train programmers

Nebraska is taking a deeper dive into domestic violence-related deaths to understand and prevent them

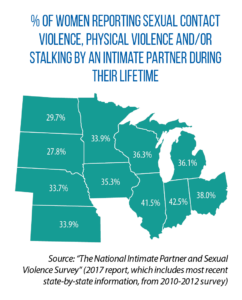

When he first began working on a bill to create an administrative body to examine domestic abuse-related deaths, Sen. Tom Brandt says, Nebraska was one of nine states that did not have such a review team in place. The absence of one made it more difficult to identify patterns of behavior and implement preventive measures. (A 2021 report from the National Domestic Violence Fatality Review Initiative also found that Illinois and Wisconsin had no or limited-activity review teams in place.)

When he first began working on a bill to create an administrative body to examine domestic abuse-related deaths, Sen. Tom Brandt says, Nebraska was one of nine states that did not have such a review team in place. The absence of one made it more difficult to identify patterns of behavior and implement preventive measures. (A 2021 report from the National Domestic Violence Fatality Review Initiative also found that Illinois and Wisconsin had no or limited-activity review teams in place.)

Working with victims’ families, advocacy groups and others, Brandt developed the framework for a State Domestic Abuse Death Review Team. Run out of the attorney general’s office, the team would investigate contributing factors to these deaths and provide recommendations for change. Members would be privy to a large number of records associated with individual cases, including, when applicable, information from the state prisons.

Brandt initially thought his bill would only get a hearing, and not pass, as it was getting late into the Unicameral’s 2022 session. However, during that hearing, another senator, Wendy DeBoer, asked to include the measure in her own omnibus priority bill, LB 741. “That happens like zero times — that somebody asks to include somebody else’s bill,” Brandt says.

LB 741 passed unanimously and was signed into law in April. The result: Brandt’s vision for a Domestic Abuse Death Review Team is now a reality.