Expunge? Seal? States re-examining laws that determine fate of conviction records for low-level marijuana possession offenses

In early October, President Biden signed an executive order pardoning about 6,500 individuals who were federally convicted of simple marijuana possession between 1992 and 2021. He also urged governors to follow suit by pardoning state-level marijuana possession convictions.

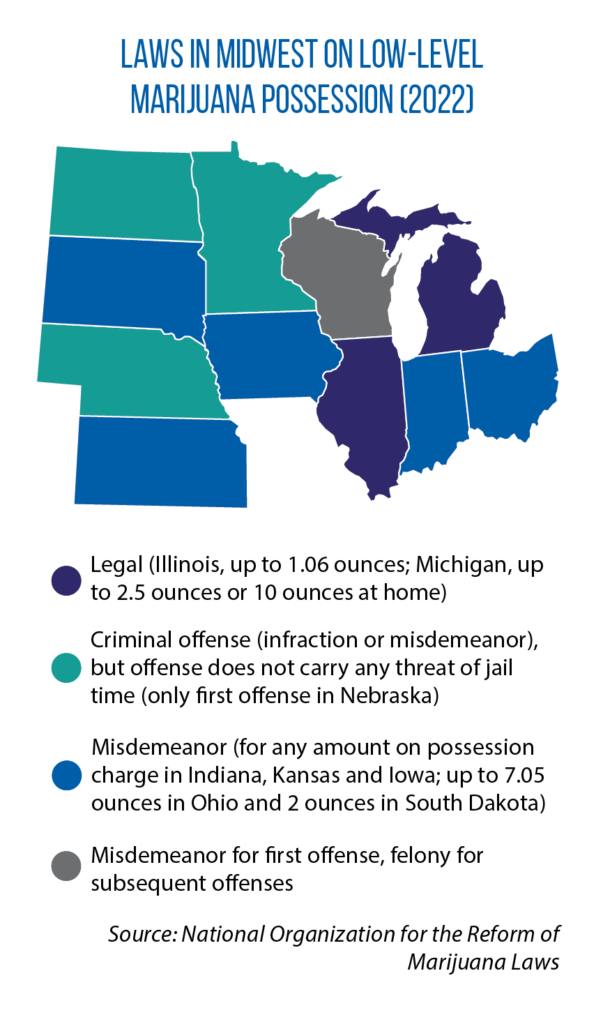

While all Midwestern states allow people to petition for such pardons, they diverge over what to do with possession conviction records.

Illinois’ 2019 legislation legalizing recreational marijuana (HB 1438) includes language to automatically expunge most past convictions, while Michigan lets people apply to have their records sealed. Under a 2020 law (HB 4980), Michigan will begin automatically sealing a limited number of certain convictions, but only after seven years.

Illinois’ 2019 legislation legalizing recreational marijuana (HB 1438) includes language to automatically expunge most past convictions, while Michigan lets people apply to have their records sealed. Under a 2020 law (HB 4980), Michigan will begin automatically sealing a limited number of certain convictions, but only after seven years.

Legislators and policymakers in other states remain uncertain, or unconvinced. In North Dakota, for example, the debate over how best to address low-level possession and related criminal records has evolved over the past four years.

A failed 2018 ballot initiative sought to not only legalize recreational cannabis, but also automatically expunge all nonviolent marijuana convictions within 30 days of passage (excluding sale-to-minor convictions).

Rep. Shannon Roers Jones, co-chair of the Midwestern Legislative Conference’s Criminal Justice & Public Safety Committee, says although she spoke out against the measure at the time, she found common ground with advocates regarding decriminalization and clemency.

In the 2019 legislative session, she sponsored two bills on that front.

In the 2019 legislative session, she sponsored two bills on that front.

The first, HB 1155, would have made possession of drug paraphernalia and up to an ounce of marijuana a noncriminal, fineable offense instead of a misdemeanor.

“My thought process is more on weighing the harm to the person of consuming marijuana versus the harm to that person of having a criminal record that impacts [his or her] ability to hold a job, to find housing, to join the military,” Roers Jones says.

HB 1155 didn’t advance, but parts of it became HB 1050, which was signed into law that year, making possession of less than half an ounce of marijuana a criminal infraction. Subsequent infractions within a year elevate the penalty to a misdemeanor.

Another of her bills (HB 1256) created a way for people to petition to seal records of nonviolent, non-sex-offense convictions if they have been in good standing for three years.

Courts were also given the ability to grant “certificates of rehabilitation” to which people can refer for criminal background checks.

“I think that’s maybe even more valuable than just having the record sealed, because we all know that if you do a Google search for somebody’s name, that information is still going to be out there,” she says.

In 2021, legislators passed HB 1196, allowing multiple eligible convictions to be sealed at once rather than just the most recent one.

And shortly following the passage of HB 1050, the state’s Pardon Advisory Board adopted a policy to allow people convicted specifically of low-level marijuana possession to apply for a pardon in a more simplified fashion. According to Roers Jones, as of fall 2022, 83 people had received such pardons. (Around 175,000 North Dakotans are eligible.)

Expungement vs. sealing

Expungement vs. sealing

Requiring offenders to apply to seal a marijuana record is common in multiple states. Some advocates say a better process would include automatic and full expungement — the actual destruction of physical records instead of sealing them from public view.

“When they are sealed or set aside, there are certain circumstances under which those records are still available for review by either law enforcement or the court system, and in some cases third-party background check companies,” says Morgan Fox, political director for the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws.

Roers Jones says erasing all traces of a criminal offense is nearly impossible in a digital age, while full expungement could complicate high-level background checks such as for federal employment. Instituting an automatic expungement process would put undue burdens and costs on state court systems, she adds.

“If the burden for sealing those records goes back to the court and they miss something, does that create a liability to someone whose record they haven’t sealed?”

Michigan Rep. Graham Filler agrees.

In 2020, he led the passage of a package of bipartisan expungement-reform bills, one of which, HB 4982, allows individuals convicted of a marijuana misdemeanor offense to petition to have their conviction sealed. (Prior to legalization, possession of any amount of marijuana was a misdemeanor.)

After law enforcement input, legislators included a 60-day window for prosecutors to rebut the sealing of a person’s record.

“Law enforcement said, ‘Look, there are a couple of cases where an individual was clearly a high-level drug dealer. … For whatever reason, they pled down to use and possession for marijuana,” Filler says. “That’s really bad in a community when that individual is now going to automatically be able to wipe that away.”

Illinois’ law requires that all relevant records for previous possession arrests for up to 1.06 ounces (the current legal limit) be expunged by January 2025. For previous convictions of nonviolent possession charges, State Police had until mid-2020 to identify and share records with the Prisoner Review Board to evaluate for possible pardons. The board, before submitting its recommendations to the governor, informs county state’s attorneys and gives them 60 days to object. The attorney general then petitions courts to expunge the criminal records of those granted a pardon.

Illinois’ law requires that all relevant records for previous possession arrests for up to 1.06 ounces (the current legal limit) be expunged by January 2025. For previous convictions of nonviolent possession charges, State Police had until mid-2020 to identify and share records with the Prisoner Review Board to evaluate for possible pardons. The board, before submitting its recommendations to the governor, informs county state’s attorneys and gives them 60 days to object. The attorney general then petitions courts to expunge the criminal records of those granted a pardon.

People convicted of possessing more than 1.06 ounces but less than 17.64 ounces can petition the courts to have their records expunged (with input from state county attorneys). Illinois Gov. JB Pritzker said in October that nearly 800,000 convictions had either been pardoned or expunged.

A federal issue

Some Midwestern governors reject President Biden’s suggestion. Nebraska Gov. Pete Ricketts and Attorney General Doug Petersen released a joint statement calling the policy “ill-advised.”

In his statement, Indiana Gov. Eric Holcomb said Biden should work to change federal law, “especially if he is requesting governors to overturn the work local prosecutors have done by simply enforcing the law.”

“Until these federal law changes occur, I can’t in good conscience consider issuing blanket pardons for all such offenders,” Holcomb said.

Fox says Biden’s action is a step in the right direction, but that Congress should extend federal pardons farther back than 1992, make people eligible for pardons regardless of immigration status, and completely de-list cannabis from the Controlled Substances Act. He also referenced federal legislation (HR 6129) that would award grants to states to help reduce the financial burden of expunging cannabis-related convictions.