Though nearly all Midwest states allow for compassionate release of elderly, terminally ill incarcerated residents, obstacles often stand in way

For people lucky enough to reach an advanced age, the ability to receive competent geriatric care and “die with dignity” is enviable.

For elderly individuals in incarceration, such end-of-life experiences are even rarer.

With the exception of Iowa, every state has processes in place allowing for the release of certain incarcerated offenders who are nearing the end of their lives — commonly referred to as “compassionate release.”

However, according to comparative state research conducted by FAMM (formerly Families Against Mandatory Minimums), such releases continue to be used infrequently due to numerous bureaucratic barriers.

Mary Price, general counsel for FAMM and author of the 2018 report “Everywhere and Nowhere: Compassionate Release in the States,” says the issue is not whether prison facilities are capable or equipped to care for elderly offenders, but whether such an environment is ever appropriate for terminal individuals.

Mary Price, general counsel for FAMM and author of the 2018 report “Everywhere and Nowhere: Compassionate Release in the States,” says the issue is not whether prison facilities are capable or equipped to care for elderly offenders, but whether such an environment is ever appropriate for terminal individuals.

“Prisons aren’t the place to host people who are so ill that they may not be able to comprehend the fact of their imprisonment or to benefit at all from it,” Price says. “Imprisonment has lost any meaning for them or for us as a society. We are no longer in danger of being harmed by that person, if we were, or concerned about whether they would re-offend.”

Between 1993 and 2013, the number of people age 55 years and older housed in state prisons increased by 400 percent, accounting for 10 percent of overall state prison populations in 2013, according to the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Others have estimated this age group could represent close to one-third of all state and federal prison populations by 2030.

“It’s very costly if you don’t have a [compassionate release] program or you have a program that doesn’t get used — because those people are very expensive to imprison,” says Price. “They may have durable medical needs in terms of equipment. They have to be housed sometimes in special units. They may need ventilators or round-the-clock nursing care.”

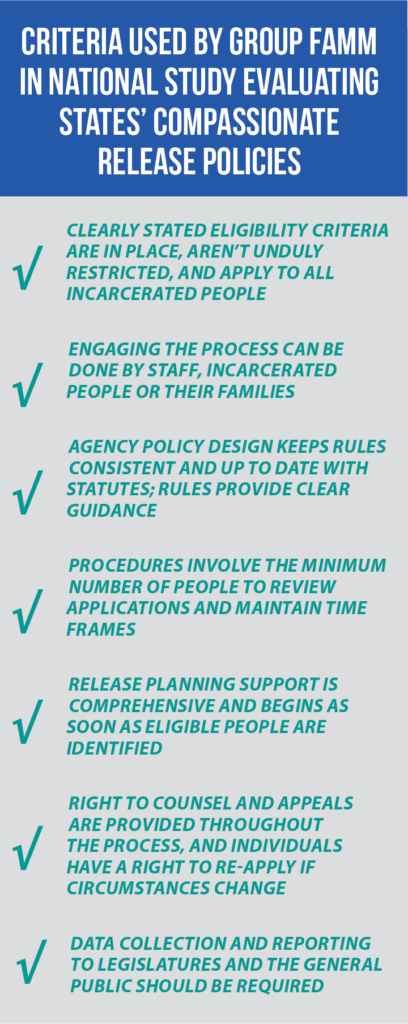

In an effort to raise awareness amongst policymakers, FAMM in October released evaluations of all states’ compassionate release policies, based on elements ranging from eligibility criteria and release procedures to data collection and right to counsel (see graphic for the organization’s full rubric).

Need for greater clarity

Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota and Wisconsin received variations of an “F” grade, yet got high marks for certain aspects of their compassionate release policies.

The eligibility criteria used in Wisconsin’s “sentence modification due to extraordinary health condition or age” policy, for example, was credited as a “model of clarity and breadth” for providing “very clear descriptions of what constitutes extraordinary health conditions and includes easy-to-understand examples of qualifying conditions.”

The eligibility criteria used in Wisconsin’s “sentence modification due to extraordinary health condition or age” policy, for example, was credited as a “model of clarity and breadth” for providing “very clear descriptions of what constitutes extraordinary health conditions and includes easy-to-understand examples of qualifying conditions.”

FAMM also deemed Wisconsin’s release planning policies as the “crown jewel” of the program because, “it starts early, is comprehensive, and includes assistance with applying for benefits and finding housing and funding.”

In addition, Illinois, South Dakota, and Wisconsin were commended for not revoking an offender’s compassionate release if the person’s medical condition improves.

Nonetheless, most states in the region earned low grades for possessing policies that were deemed confusing or contradictory, place undue burden on impaired offenders to start the application process, use vague or restrictive definitions of what it means to be “near death,” and other reasons.

Iowa, which does not currently provide for compassionate release, was the only state to receive an automatic zero grade from FAMM.

Attempts to change the state’s policies have been made, however. In 2021, for example, HF 377 included a provision that would have allowed for people convicted of a Class A felony offense — which usually includes a life sentence — to be able to petition for a commutation if diagnosed with a terminal illness or they became medically incapacitated.

Although that bill never made it out of committee, a neighboring state did pass a similar proposal that same year.

The Illinois model

Illinois was the only Midwestern state (and one of just five nationwide) to receive an “A.” However, this lauded status was not always the case.

“The process for applying for medical release was complicated, burdensome, took a very long time and required executive action by the governor,” says Illinois Rep. Will Guzzardi.

“The process for applying for medical release was complicated, burdensome, took a very long time and required executive action by the governor,” says Illinois Rep. Will Guzzardi.

That led him in 2021 to introduce the Joe Coleman Medical Release Act, a bill (HB 3665) named after a Vietnam War veteran who had been in prison since the early 1980s for multiple robberies and whose family had tried for years to secure his release due to failing health.

“When Joe Jr., Joe’s son, was in the car driving to Springfield to get the final paperwork, it had to be notarized and then hand-delivered to some bureaucrat in Springfield in order to secure his father’s release, and as he was in the car on the road to Springfield, his father passed away in prison,” Guzzardi recalls.

HB 3665 was signed into law that August. As a result, offenders and other parties (for example, family members, attorneys and doctors) now can petition the Prisoner Review Board for an incarcerated individual to transition to mandatory supervised release if he or she is suffering from a terminal illness or is deemed medically incapacitated.

“Terminal illness” is defined as an incurable condition that will most likely result in death within 18 months. “Medically incapacitated” is defined as a medical condition or cognitive disorder, developed after sentencing, that prevents an individual from completing more than one activity of daily living — for example, feeding, personal hygiene, dressing or toileting.

“Terminal illness” is defined as an incurable condition that will most likely result in death within 18 months. “Medically incapacitated” is defined as a medical condition or cognitive disorder, developed after sentencing, that prevents an individual from completing more than one activity of daily living — for example, feeding, personal hygiene, dressing or toileting.

The new policy applies retroactively to all incarcerated individuals regardless of when they were sentenced. Applicants can file for compassionate release multiple times, and the Prisoner Review Board must consider victim reports when evaluating release claims.

Despite receiving an overall high score, Illinois’ release planning policy earned low marks from FAMM for placing too much of the onus on the petitioners to find housing and medical support upon release. In comparison, states such as Kansas, Minnesota and Wisconsin earned praise in the FAMM study for their release planning procedures.

Guzzardi agrees this is an area that needs to be addressed.

“The [Illinois Department of Corrections] has not yet created a strong enough system to connect these folks who are going home with the medical care they’re undeniably going to need,” he says.

“So far, most of the successful petitions under the act have been with the help of nonprofit legal aid clinics — specifically the Illinois Prison Project … But ultimately, this shouldn’t be an ad hoc thing that falls to the well-intentioned nonprofit sector. This should be the responsibility of the state.”