States use different models to govern K-12 systems, and these structures are subject to change based, in part, on the will of legislatures

Schools across the region and nation are still reeling, to some degree, from the disruption that the COVID-19 pandemic had on students’ education.

On the 2022 National Assessment of Educational Progress, average student test scores in fourth- and eighth-grade math and reading fell in every Midwestern state — with one exception — compared to results from three years earlier. (Illinois’ fourth-grade math and reading scores were constant with 2019 averages.)

This decline in academic performance, combined with a mix of contentious issues and changing priorities in K-12 education, has led some lawmakers to take a closer look at how school systems are governed and policies are made.

Proposed overhaul in Ohio

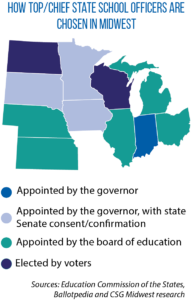

In the Midwest, several different education governance models are used.

In the Midwest, several different education governance models are used.

Wisconsin and North Dakota have independently elected state superintendents, a position enshrined in each state’s constitution. Indiana also had an elected state superintendent until 2021, when a legislative change (HB 1005 of 2019) made the top school official a governor-appointed rather than elected position.

Governors also have considerable control of state-level education leadership in Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota and South Dakota. In those states, the governors appoint members of the state boards of education and/or the chief state school officer (see maps).

Ohio has a hybrid model of sorts, a 19-member State Board of Education with 11 members chosen by voters and eight appointed by the governor.

This board is constitutionally required to exist, but Ohio Sen. Bill Reineke believes many of its powers and responsibilities should be moved to the governor’s office.

For years, he has advocated for a cabinet-level administrator that would have jurisdiction over key policy areas, such as K-12 standards and assessments, school district report cards, teacher evaluation systems, and the distribution of state aid.

The State Board of Education would retain authority over certain administrative duties.

Last year, Reineke sought this kind of overhaul in governance with SB 178. At the time, Ohio had been without a full-time state superintendent for over a year, and Reineke and others felt a lack of leadership had contributed to lower test scores and an increased need for academic remediation.

He says the proposal is partly about improving accountability, by making the top school chief part of the governor’s cabinet, but also about modernizing the mission of Ohio’s K-12 education system.

The proposed cabinet-level position would oversee a “Department of Education and Workforce.” Along with adding “workforce” to the department’s title, Reineke envisions creating a new division focused entirely on career and technical education.

“Currently we have 700-plus employees at the Ohio Department of Education,” he says.

“Currently we have 700-plus employees at the Ohio Department of Education,” he says.

“When I started this quest five years ago, there were three [staffers] in career tech. Today, we’re all the way up to 37, and I just feel like we should have a larger percentage of people really focusing in on these programs.”

SB 178 passed the Senate in December 2022. Language from this legislation was ultimately included in a larger (and contentious) House bill (HB 151) that did not pass.

‘Sing out of same hymnal’

Paolo DeMaria, president and CEO of the National Association of State Boards of Education and a former Ohio state superintendent, says debates over education governance structures can sometimes be a manifestation of something else.

When SB 178 was debated on the Senate floor, for example, some proponents of the bill cited frustrations with unfunded state mandates and how a school-choice scholarship program was being carried out as justification for a new governance structure.

Twenty-five years ago, a high-profile debate over education policy in Minnesota led lawmakers to end their state’s structure and replace it with one unique in the Midwest — a governor-appointed, cabinet-level education commissioner, with no state board of education. Minnesota’s elimination of the governor-appointed board marked the first time any U.S. state had made such a move.

At the time, Education Week notes, one catalyst for this change was negative reaction to a board-approved policy known as the “diversity rule,” which required Minnesota districts to develop plans to address student achievement gaps along racial and ethnic lines.

At the time, Education Week notes, one catalyst for this change was negative reaction to a board-approved policy known as the “diversity rule,” which required Minnesota districts to develop plans to address student achievement gaps along racial and ethnic lines.

Rep. Gene Pelowski — who voted for the bill at the time — says K-12 education policymaking in Minnesota today is dominated by the Legislature and the governor. He worries about the level of “meddling” that now comes from St. Paul.

“A one-size-fits-all [approach] on what is going to be done in the classroom has probably done more harm to education than anything else, coupled with statewide testing,” he believes.

Regardless of the governance model, DeMaria notes, legislatures have significant authority over education practices.

“The fundamental question is, Are there certain governance models that are better than others? And the answer to that is ‘no.’ ”

Instead, he says, the emphasis should be placed on an effective sharing of responsibilities and goals.

“When I go to a state and I see the board, and the superintendent, and the governor, and the legislature all singing out of the same hymnal and working collaboratively on a common agenda, that’s where you actually [move forward],” says DeMaria, who cites Mississippi’s successful efforts over the past decade to improve literacy scores as an example.

Controversy in Nebraska

Controversy in Nebraska

DeMaria acknowledges because education has always been a political issue, politics undeniably plays a role in the few states that have elected state board of education positions.

“If I am running in a state and I know that to win I have to accumulate a certain number of votes, then that goes into the platform-setting and the representations that are made,” he said in an interview last year with Politico.

Three Midwestern states — Kansas, Michigan and Nebraska — have all members of their respective state boards of education publicly elected. During the 2022 elections in Nebraska, there was heightened interest in these races.

That’s in large part because of a controversy which arose one year prior, when the Nebraska State Board of Education released draft proposals for state health education standards. The first draft was met with heavy criticism due to the inclusion of learning goals centered around gender identity and descriptions of sexual acts starting in elementary grades. The second draft made significant

changes, but the board ultimately voted to postpone implementation indefinitely.

A significant legislative and political fallout ensued.

During Nebraska’s 2022 legislative session, an unsuccessful proposal (LB 768) sought to prevent the State Board of Education from adopting standards unrelated to reading, writing, math, science or social studies.

Meanwhile, a coalition of people opposing the 2021 sex education standards were able to transform a Facebook group into a political action committee that backed several candidates for the Nebraska State Board of Education. Most of those candidates won their election in November, resulting in a major change in the makeup of the board.