With ‘science of reading’ laws, states eye turnaround in recent trends

Test scores have fallen across the region; new legislative measures include investments in reading instruction — and sometimes requirements on how the subject is taught

In the Midwest, drops in students’ test scores on reading are widespread and, in many states, predate the COVID-19 pandemic. One group that has taken notice and recent action to reverse that trend: state legislators.

“Kids that don’t know how to read or aren’t reading at a proficient level by third grade are exponentially more likely to drop out of school,” notes Indiana Rep. Jake Teshka, chief author of a new law on reading in his state.

The research is definitive on that point, he adds, and the consequences also are clear. Young people don’t attain the postsecondary credentials they need for economic and career success, and the state as a whole is left with a workforce problem.

The research is definitive on that point, he adds, and the consequences also are clear. Young people don’t attain the postsecondary credentials they need for economic and career success, and the state as a whole is left with a workforce problem.

“Jobs coming to Indiana are increasingly going to require some sort of postsecondary education,” Teshka adds.

He believes a new law in Indiana can help turn around those trends in reading performance.

In Wisconsin, Rep. Joel Kitchens authored a like-minded bill in his home state, with some of the same long-term concerns about student outcomes in mind.

“When people ask me, ‘What scares you the most about the future,’ [it] is seeing more and more people trapped in that cycle of poverty, one generation after the other,” Kitchens says. “The only chance we have of breaking that is education. And basically, if we don’t get [students] reading early, it’s just not going to happen.”

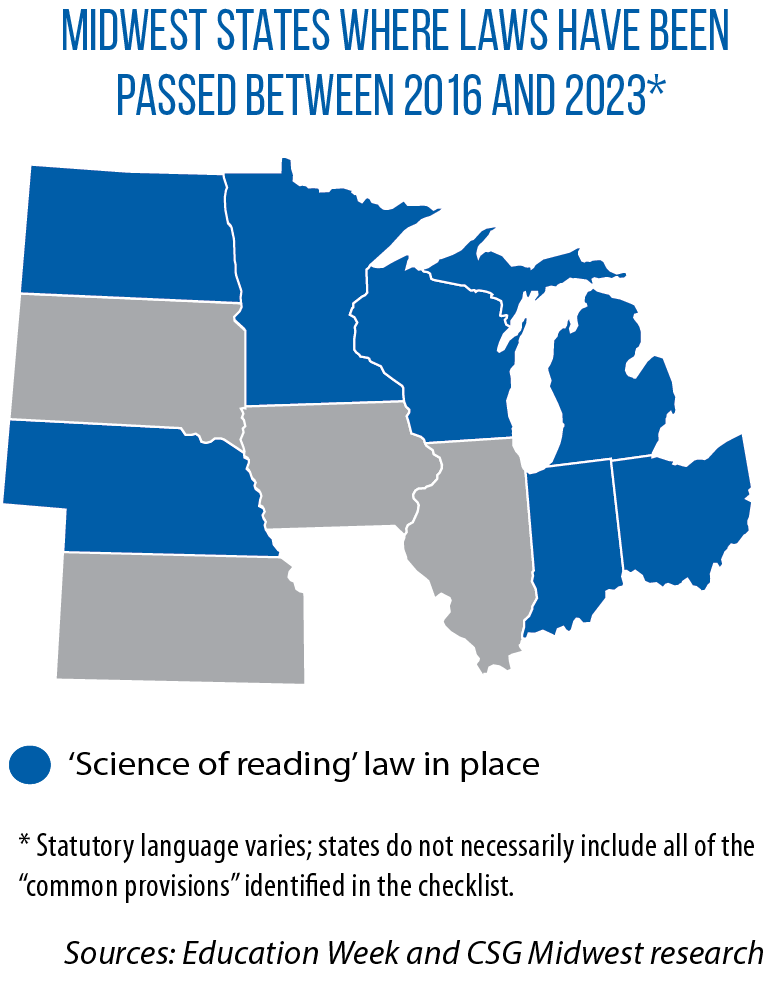

Laws in Indiana, Wisconsin and other states are revamping schools’ reading instructional strategies and promoting (sometimes requiring) approaches that adhere to what is known as the “science of reading,” or SoR.

Context of new laws on reading instruction

Although not comprised of a universally recognized curriculum model, SoR is an approach to reading instruction that emphasizes phonetic learning, the sounding out of letters and words. For the last few decades, a “reading war” of sorts has waged throughout academia regarding reading instruction.

Is phonics the best approach? Or do other strategies work best for students?

For example, with the “three-cueing” model, an emphasis is placed on students using context clues and analyzing syntax in order to understand written language. In practice, a teacher using this method would prompt students, or “cue” them, to ascertain the meaning of a word in a sentence by asking a series of questions: Does it make sense? Does it sound right? Does it look right?

For example, with the “three-cueing” model, an emphasis is placed on students using context clues and analyzing syntax in order to understand written language. In practice, a teacher using this method would prompt students, or “cue” them, to ascertain the meaning of a word in a sentence by asking a series of questions: Does it make sense? Does it sound right? Does it look right?

The problem with this method, according to critics, is this style of instruction simply makes students better guessers. It’s more akin to the strategies used by people who have difficulty reading, they say.

Proponents of the recently enacted state laws say SoR is more closely aligned with the tenets of cognitive science. That’s because lessons built on phonemic awareness and phonics better connect how children auditorily learn how to speak, a primal ability of humans, to how they learn to read, a more complex and relatively modern skill.

“We have tangible physical evidence as far as the way that the brain works and the way that orthographic mapping works and the way that we commit words to memory,” Teshka says. “And the process by which we do that is all encompassed in this body of research called ‘science of reading.’ ”

Teshka’s goal with this year’s HB 1558 (signed into law in May) is to make sure evidence-based instruction from that research is used in Indiana classrooms.

The SoR movement has also gained traction in part because of recent progress in Mississippi, a state that traditionally has had among the nation’s lowest reading scores. A turnaround has occurred in that state over the past decade, since passage of the Literacy-Based Promotion Act and the Early Learning Collaborative Act.

With those laws in place, money started going toward SoR-based professional development for all early-grade teachers and school administrators.

Mississippi schools also received new resources from the state, including literacy coaches — individuals with advanced degrees who work with teachers as well as one-on-one with students.

“[The] coaches were put through a rigorous interview process to make sure they had the right background knowledge and knew how to work with adults,” former Mississippi State Superintendent Carey Wright said during an interview earlier this year with McKinsey & Company.

“We were strategic in how we deployed these people and how we built capacity for teachers and leaders.”

Between 2013 and 2019, average fourth-grade reading scores in Mississippi increased significantly. Additionally, 65 percent of students in this grade were reading at a basic level or higher, up from 53 percent in 2013. These advances were also seen across multiple racial and ethnic groups.

Spread of new reading laws in Midwest

Mississippi’s success story has given rise to new SoR laws in other states, including three in the Midwest this year alone: Indiana (HB 1558/1590), Ohio (HB 33) and Wisconsin (AB 321).

These laws require classroom instruction and teacher training in SoR methods, and also generally prohibit use of the three-cueing model in the future (with exceptions for students with special needs or English language learners where this method might be preferred and work best).

These states also provide funding for new literacy coaches to help deliver evidence-based reading instruction to students.

In Indiana, the transition to SoR is scheduled to happen rather quickly.

At public and charter schools where fewer than 70 percent of students earn a passing score on a state reading evaluation, an SoR-only curriculum must be in place next school year. A similar timeline applies to Indiana’s teacher-preparation programs, and a new literacy endorsement for teacher-candidate graduates will begin being offered in July 2025.

“It is aggressive and it’s intentionally so,” Teshka says. “If we know what works, we need to go all in.”

“It is aggressive and it’s intentionally so,” Teshka says. “If we know what works, we need to go all in.”

That’s also why he and other lawmakers ultimately rejected the idea of allowing hybrid approaches, which incorporate elements of both SoR and three-cueing. These hybrid methods are sometimes referred to as “blended” or “balanced” literacy. (The new laws in Ohio and Wisconsin also favor SoR alone, rather than a hybrid approach.)

Over the next two years, Indiana is allocating $40 million to train teachers on SoR, to recruit literacy and instructional coaches, and to allow teachers who graduated before 2025 to earn a new literacy endorsement (and earn differentiated pay). This new appropriation builds on big investments in reading instruction in the state in recent years, including a multimillion-dollar Lilly Endowment grant.

Ohio legislators also were able to get a SoR measure passed this year due in part to promised funding.

That state’s new approach to reading instruction came not through stand-alone legislation, but via provisions in the two-year budget. It includes $86 million for professional development, $64 million for curriculum and instructional materials, and $18 million for literacy coaches, according to the Ohio Capital Journal.

Ohio schools will need to transition to SoR-only instruction by next fall, and all teachers and administrators will need to complete training in SoR instructional strategies by June 2025.

Gov. Mike DeWine has been one of the biggest proponents of this new approach to literacy instruction.

“The jury has returned, the evidence is clear, the verdict is in,” DeWine said in his State of the State address earlier this year.

Throughout the spring, he traveled the state to classrooms that were already using the SoR approach, and his office produced a video that included testimonials from teachers, administrators and students.

In addition, the governor also launched the ReadOhio Initiative which seeks to provide free digital resources, a “toolkit” for educators, and promotes existing literacy resources like the Dolly Parton Imagination Library.

The path to a new reading law in Wisconsin was quite different.

In previous years, Gov. Tony Evers had vetoed legislation calling for new assessments of reading proficiency among students in the early grades. Those past differences, Rep. Kitchens says, had resulted in an air of distrust between the legislative and executive branches.

However, bipartisan consensus built for the legislative proposal AB 321 (Kitchens was the chief sponsor) as various K-12 and university leaders voiced support for the SoR model.

“I went to DPI [the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction] at the beginning of the session, and was very surprised that all of a sudden they were kind of on board with me,” Kitchens says.

“Then, I set up an appointment to talk to the governor, and he was very supportive as well.”

Early on in the legislative process, however, bipartisan support for the measure was almost upended over a provision that would have required schools to “hold back” third-graders if they did not pass a newly designed reading assessment.

“The education community, certainly the governor’s office, was vehemently opposed to putting in a policy like that,” Kitchens says.

“Honestly, on my part, that was never an issue. … Very often that is not what’s in the kids’ best interest.”

The provision was taken out, and Evers signed AB 321 in July.

Under Wisconsin’s new law, school districts have until July 2025 to write individualized policies for how they will intervene and help students with low reading scores as they move from third grade to fourth grade.

Like Mississippi, Wisconsin will take a targeted approach in how it deploys new state-funded literacy coaches — they’ll initially be designated for 50 schools with the lowest reading scores and another 50 schools with the greatest gap between proficient and struggling readers.

Kitchens adds that language in the law will ensure that literacy coaches are spread across Wisconsin, rather than concentrated in only a few districts.

Kitchens adds that language in the law will ensure that literacy coaches are spread across Wisconsin, rather than concentrated in only a few districts.

Part of his vision for AB 321 is that schools will work with and learn from each other on what reading strategies and interventions are working best.

“And I think districts will sort of grow their own coaches as well through this process,” Kitchens says.

A new council (appointed by legislative leaders and Wisconsin’s state superintendent of public instruction) will submit recommendations later this year on a new literacy curriculum as well as the instructional materials to be used in kindergarten through third grade.

“It’s going to be a challenge,” Kitchens says about implementation of AB 321 and the law’s quick turnaround time. “I think there will be some hiccups. It’s an ambitious calendar. I wish we had been able to pass the legislation earlier in the session so that we wouldn’t have that problem.”

One unique provision regarding the new council is language that bars individuals from serving in the group if they have a personal financial interest in an entity that sells or markets related reading instructional materials or trainings.

Although maybe not done consciously, this stipulation to try an alleviate any perceived conflict of interest in the curriculum making process will perhaps help to avoid a similar fate to when phonics-focused reading instruction was last strongly advocated for on a national level — by then-President George W. Bush.

Having campaigned on increased federal spending for early reading interventions and having rejected non-phonics instructional approaches, President Bush advocated for his “Reading First” initiative that emphasized curriculum based on SoR.

It was this push for the Reading First initiative that brought Bush to visit an elementary school in Sarasota, Fla., to see a phonics-incorporated reading lesson in-person — on the morning of September 11, 2001.

Support for the federal initiative, however, would eventually wane. One reason was some educators and school districts rejected the new approach simply because it was associated with a controversial president.

Another reason — which connects to the Wisconsin provision — materialized in 2006 when a U.S. Department of Education inspector general report was released and detailed how several federal officials pushed states to use specific instructional materials, assessments and consultants in which they had a personal financial stake.

Risks and pitfalls of ‘pedagogical dogma’

Mark Seidenberg, a cognitive scientist, psycholinguist and professor emeritus at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, is author of the 2017 book “Language at the Speed of Sight: How We Read, Why So Many Can’t, and What Can Be Done About It.”

Although being a supporter of reading instruction that is rooted in cognitive science, Seidenberg has expressed in speeches and blog posts that support for SoR “is at risk of turning into a new pedagogical dogma.”

“We were a little bit too successful,” he says. “We convinced people of the need for change and where to look, but now we have to deal with the fact that there isn’t a lot of understanding of the research in the pipeline.”

“There aren’t any curricula out there that are based on the ‘science of reading’. They’re just ones that are better or ‘less bad.’”

According to Seidenberg, the new laws barring three-cue strategies are a “necessary evil” that transition schools away from unscientific practices. However, he warns that much more research and work needs to be done to refine the SoR model and make it work in the classroom.

Take, for example, the five key skills outlined in Ohio’s SoR approach: phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary, fluency and comprehension. Seidenberg says these five skills are based on a National Reading Panel report first released in 2000.

“It’s focusing attention in the right area; we’re in the ballpark,” he says. “But in terms of methods that will be really effective and do things that really change the landscape, I think that’s still going to take work.”

Connecting the research from cognitive scientists with the programming in teacher-preparation courses can be a slow and complex process, one that could become much more challenging for states with quickly approaching deadlines to adopt SoR.

Although there has been a lot of emphasis on improving reading comprehension before the end of third grade, Seidenberg adds, extraneous factors mean some students may continue to struggle in later grades.

For instance, Mississippi, whose progress inspired change across the country, continues to have eighth-grade reading scores and reading levels well below national averages.

Seidenberg’s advice to legislators and education leaders: Don’t “cast adrift” the needs of these later-grade students; they need specialized reading services and supports as well.

‘Windows’ and ‘mirrors’ for young readers

Seidenberg also supports reading instruction that accounts for the language and vocabulary that students are accustomed to at their homes. This strategy is one part of a comprehensive new statewide literacy plan being developed in Illinois as a result of SB 2243 (signed into law in July).

Unlike other states in the region, Illinois chose not to completely overhaul its reading curriculum or go all in on SoR. One reason may be the lack of support from the Illinois chapter of Stand for Children, whose Executive Director Jessica Handy in a blog post last year advocated for an all-of-the-above approach to reading instruction.

Instead, SB 2243 instructs the Illinois State Board of Education to develop a literacy plan that “shall consider, without limitation, evidence-based research and culturally and linguistically sustaining pedagogical approaches.”

Instead, SB 2243 instructs the Illinois State Board of Education to develop a literacy plan that “shall consider, without limitation, evidence-based research and culturally and linguistically sustaining pedagogical approaches.”

Once in place, the literacy plan will serve as the basis for new training opportunities for teachers, as well as the offering of optional microcredentials in literacy instruction starting in 2025.

“What this bill does is provide an umbrella for districts to be able to evaluate what makes sense for them,” says Rep. Laura Faver Dias, a co-sponsor of SB 2243 and a former teacher herself.

“I agree with Jessica 100 percent. We need an approach that encapsulates it all to meet all students’ needs.”

In part, the new law directs the State Board of Education to develop a literacy plan that considers the most effective methods for teaching reading to students with disabilities, to multilingual students and to bidialectal students.

“Students need windows to the world to see people that don’t live like them, that don’t look like them,” Faver Dias says. “And then they also need to see mirrors so that they can see people who do look like them and who do live like them reflected back at them.”

Common provisions in SOR laws

✓ State invests money to hire instructional coaches and to provide professional development to teachers on evidence-based reading instruction

✓ Teacher-preparation programs must align their instruction with evidence-based practices regarding the teaching of reading in the early grades

✓ Requirements are established for the type of assessments, curricula and instructional materials used by schools to identify reading difficulties among students and to measure student progress

✓ Schools and teachers are directed to use specific instructional methods for reading; they also must provide specific interventions for struggling readers

‘Nation’s Report Card’ shows drop in reading scores across Midwest between 2017 and 2022

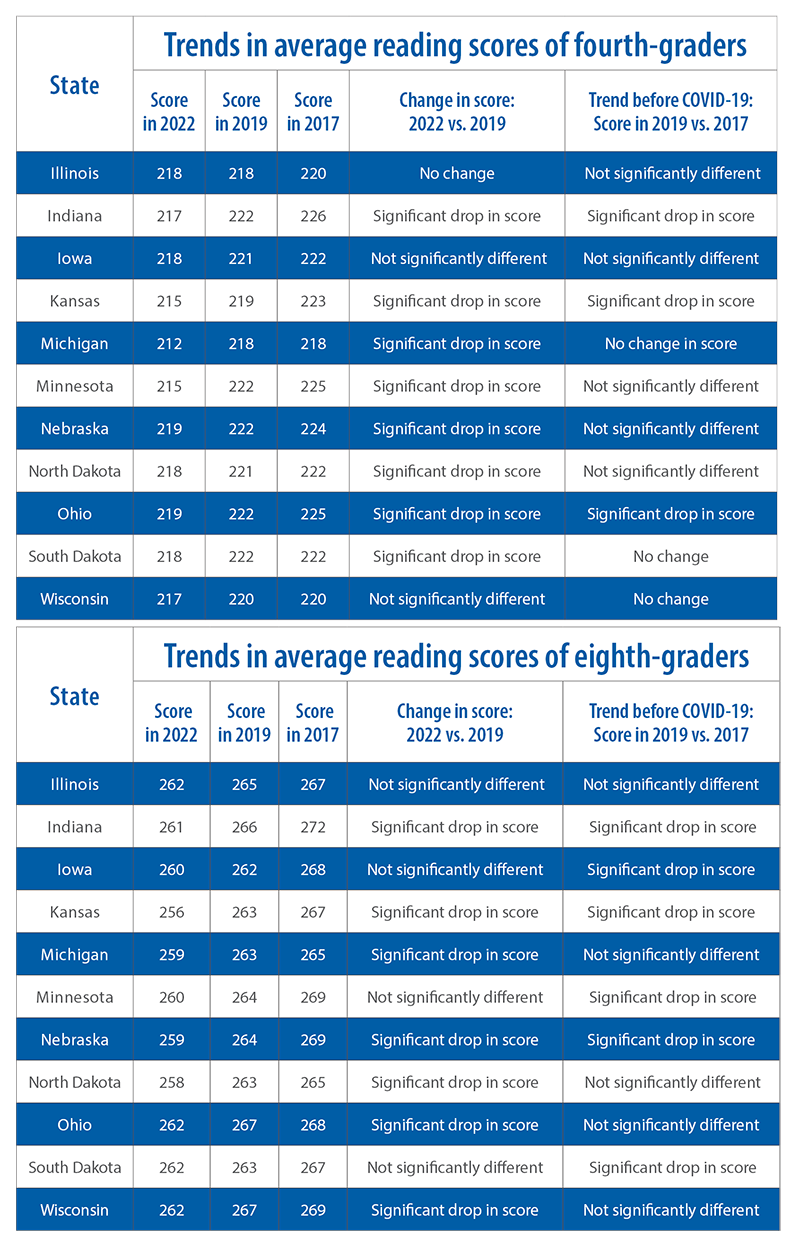

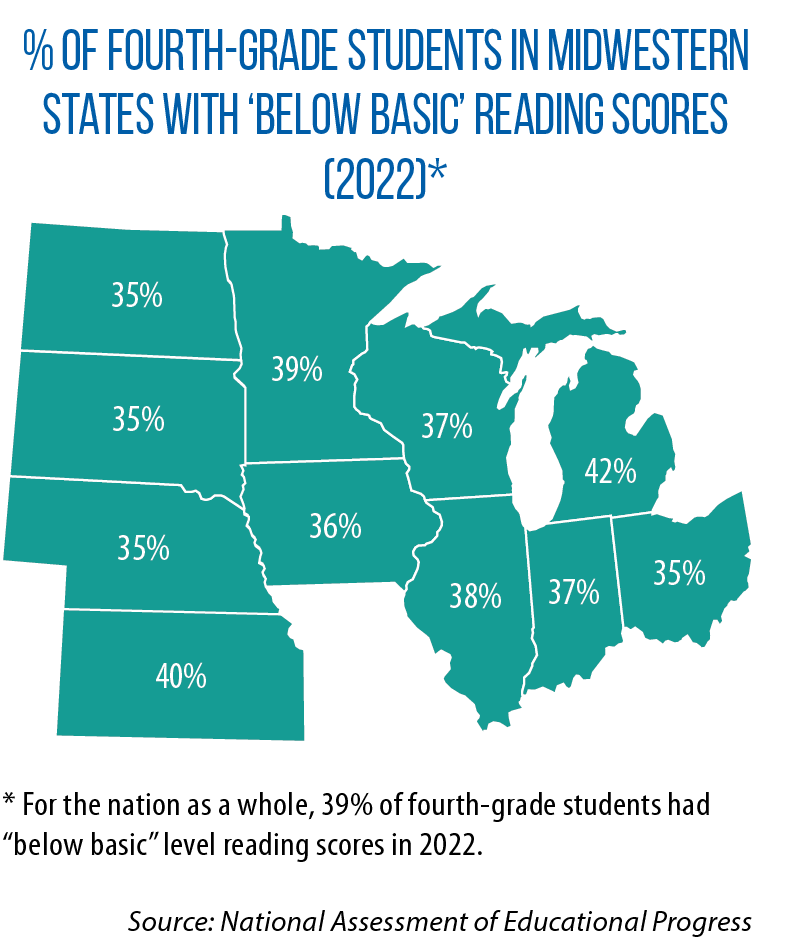

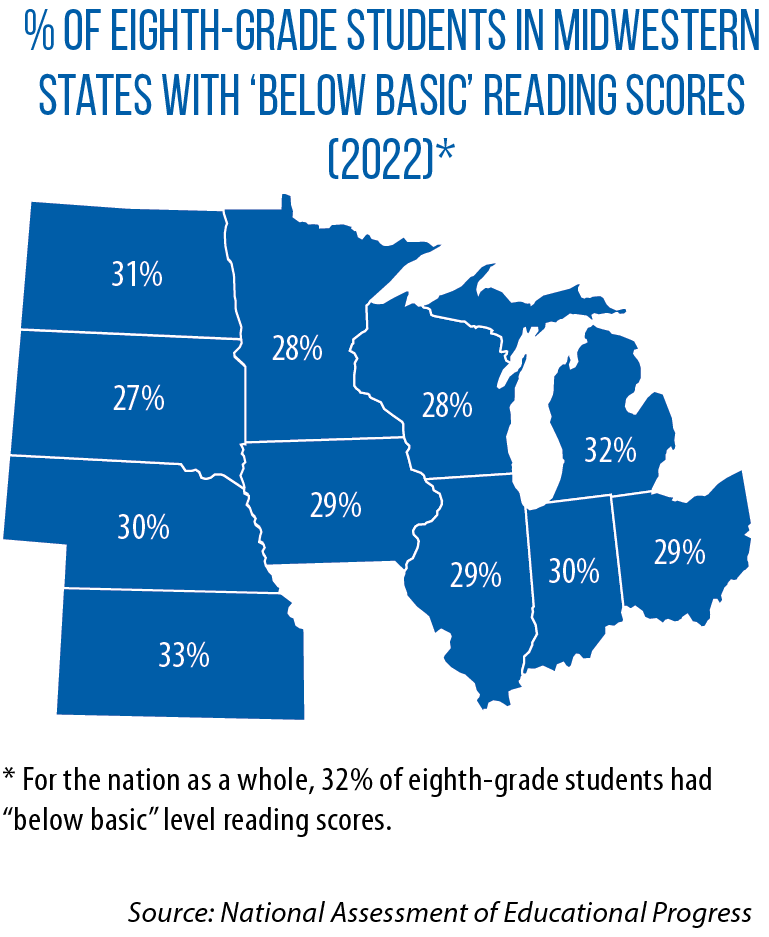

Between 2017 and 2022, average reading scores among fourth- and eighth-graders fell in each of the 11 Midwestern states, according to results from the National Assessment of Educational Progress, also known as “The Nation’s Report Card.” The changes from one test year to the next were not always classified as “statistically significant” (accounting for standard sampling and measurement errors).

However, a regionwide look at NAEP scores shows:

- Between 2019 and 2022, significant drops in the average scores of fourth-graders in eight Midwestern states: Indiana, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio and South Dakota.

- Between 2017 and 2019 (prior to learning disruptions from COVID-19), significant drops in the average scores of fourth-graders in three Midwestern states: Indiana, Kansas and Ohio.

- Between 2019 and 2022, significant drops in the average scores of eighth-graders in seven Midwestern states: Indiana, Kansas, Michigan, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio and Wisconsin.

- Between 2017 and 2019 (prior to learning disruptions from COVID-19), significant drops in the average scores of eighth-graders in six Midwestern states: Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Nebraska and South Dakota.

- For fourth-graders, a NEAP score of 208 is the low end of a basic reading level, while a score of 238 or above marks reading proficiency. Eighth-grade students with scores of between 243 and 280 are considered at a basic reading level; a score of 281 and above shows proficiency.