States, provinces in region have new plans to build immigration workforce

North Dakota and Minnesota are establishing and funding state-level offices, while Saskatchewan is pursuing more autonomy under Canada’s ‘economic immigrants’ system

For every 100 open jobs in North Dakota, about 27 people are available to fill them.

No other state had a worker shortage as severe as North Dakota’s, according to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce’s analysis of October data on the nation’s labor force.

The legislative response to this persistent workforce challenge has included a lengthy set of initiatives to build North Dakota’s homegrown talent pool and attract workers from other states.

This year, lawmakers added another tool — funding for a new Office of Legal Immigration.

“While we have done good work to promote policies that build up our own pipelines here with North Dakotans and put [individuals] into open positions, our workforce crisis also doesn’t have time to wait just for those solutions to come to fruition,” North Dakota Rep. Zachary Ista said earlier this year on the House floor, pushing for a bill to create the office.

That measure, SB 2142, became law in April.

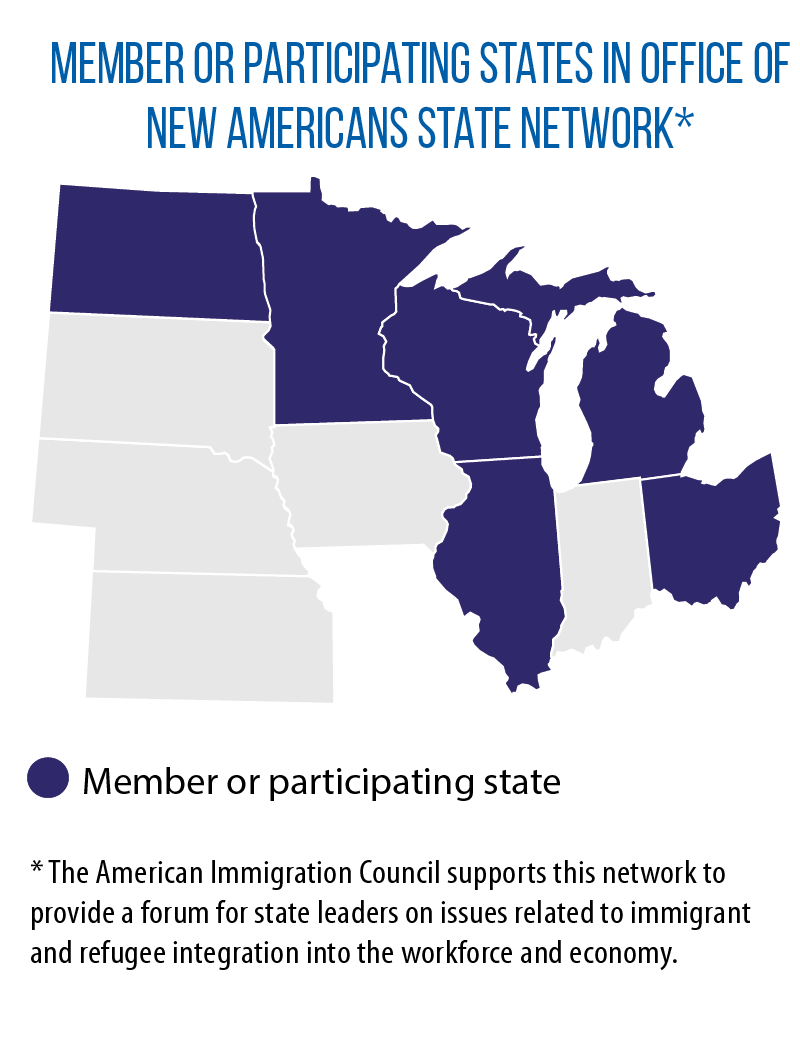

One month later, legislators in neighboring Minnesota were making permanent an Office of New Americans within that state’s Department of Employment and Economic Development.

These two new state-funded offices in the Midwest go by different names and have been given somewhat different statutory missions.

However, they share at least one common goal: help address the workforce needs of the state and its employers.

Across the border in Canada, meanwhile, a shortage of workers in provinces such as Saskatchewan is causing leaders there to seek more autonomy over immigration policy.

State will help businesses find, retain ‘foreign labor’

North Dakota’s new Office of Legal Immigration is embedded within the state’s Department of Commerce and staffed by two full-time employees (with funding for contract work as well).

Before this kind of designated team was in place, inquiries from businesses about how to obtain immigrant workers or how to navigate federal rules were handled by department staff in an ad hoc fashion.

“It’s a little bit of a phone tree that gets started,” Katie Ralston Howe, the department’s workforce director, said in a legislative committee hearing prior to passage of SB 2142. “It’s not helpful to businesses, and it’s not helpful to us either.”

Although the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services does have field offices to answer these questions, Sen. Tim Mathern says local employers don’t always find the assistance they need — not to mention that the closest office is in Minneapolis.

“We have some very large employers who are very astute about [hiring immigrant labor],” explains Mathern, author of SB 2142. “They hire attorneys, they hire other people to work the federal process.

“But small employers do not have that ability. A state office [creates] a focus of expertise that a small, local business could use.”

The initial concept for this office was to address workforce needs in the health care sector. Mathern, who represents parts of the Fargo area, is cognizant of the many African nurses working in the city and even traveled to Nigeria to see firsthand the process it took to immigrate to the United States.

In an effort to get the bill passed, however, the scope of the measure was expanded to include all industry sectors, thus helping secure support from other business groups.

The final version of SB 2142 calls for the new Office of Legal Immigration “to implement a statewide strategy to support businesses in recruiting and retaining foreign labor.” The office is also tasked with helping communities in North Dakota develop immigration integration plans.

Over the next two years, the state will appropriate $485,000 to fund the work of the office and track its progress. By 2025, the legislature wants a fee-based structure in place to help fund the office.

Mathern stresses his motivation for creating such an office was also humanitarian-based, wanting to make it easier for people fleeing oppression and violence to be able to settle in North Dakota for the long term.

“We don’t just want a worker; we want the family, we want their children, we want their descendants,” he says.

Minnesota establishes Office of New Americans

Until legislative action this year, Minnesota’s Office of New Americans (ONA) was only a temporary entity, but as part of this year’s SF 3035, legislators established the office in statute and provided state funding.

“Immigration, in my mind, should be very boring. … It should be, ‘What are the demographic needs and workforce needs?’ ” says Minnesota Rep. Sandra Feist, who also works as an immigration attorney.

“Nonetheless, it’s a very emotional, polarizing topic. Advancing bills that are explicitly about an immigration-related issue can be politically challenging.”

Early in the year, she introduced a stand-alone bill (HF 330) to make the ONA permanent; that measure ultimately got rolled into the omnibus SF 3035.

Under the new law, the office will create a strategy “to foster and promote immigrant and refugee inclusion in Minnesota so as to improve economic mobility, enhance civic participation, and improve receiving communities’ openness to immigrants and refugees.”

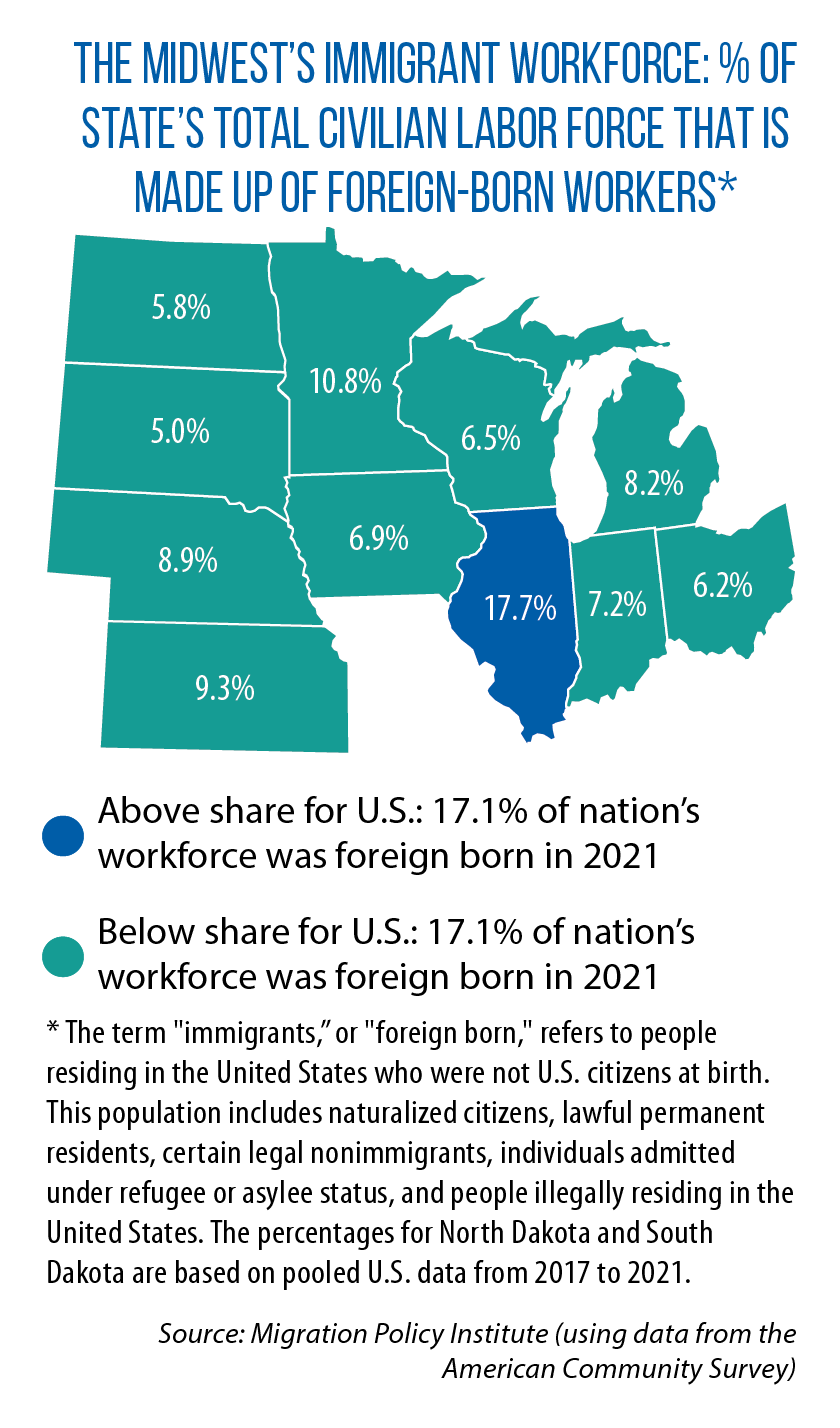

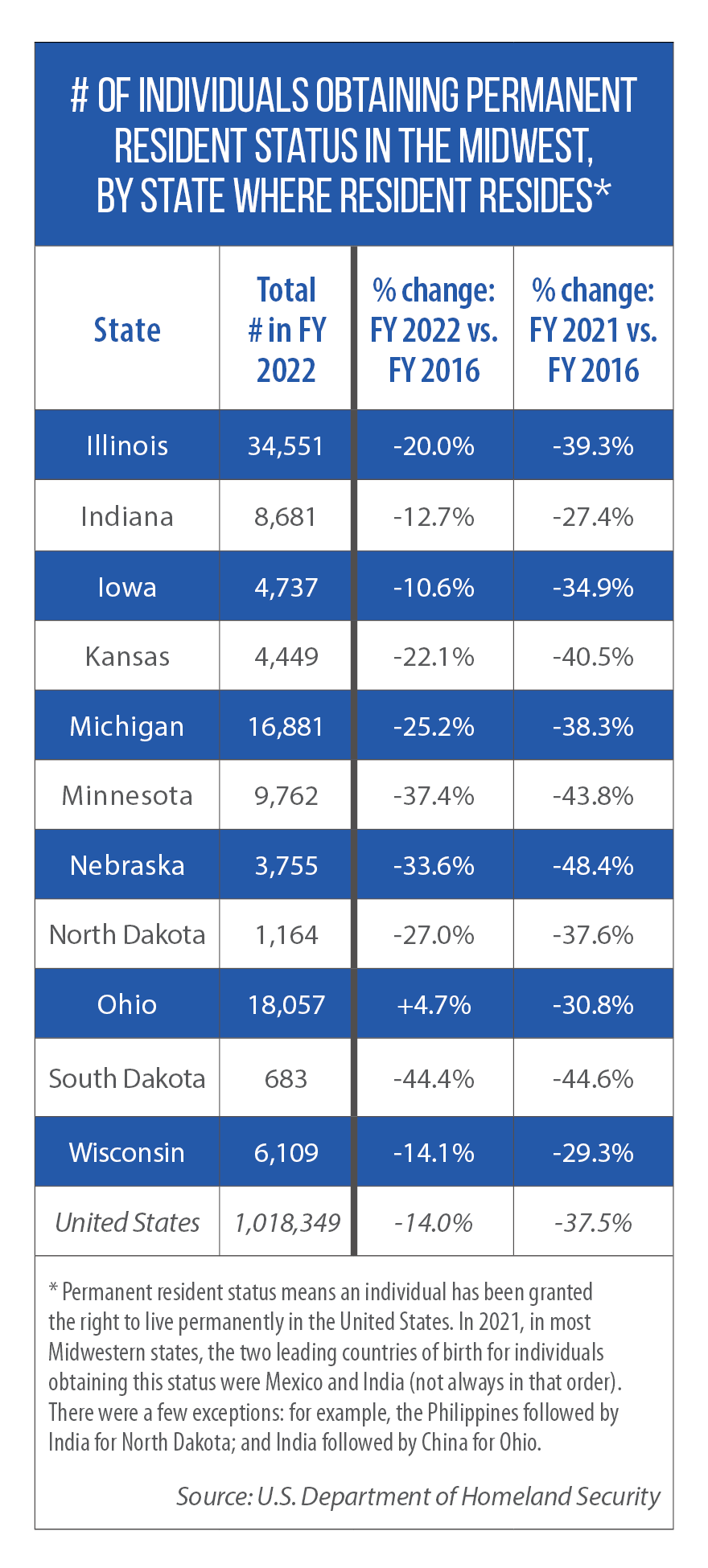

According to American Community Survey data, immigrants made up 8.5 percent of Minnesota’s population and 10.8 percent of its workforce in 2021. After Illinois, these are the highest percentages in the Midwest.

According to American Community Survey data, immigrants made up 8.5 percent of Minnesota’s population and 10.8 percent of its workforce in 2021. After Illinois, these are the highest percentages in the Midwest.

Feist describes the workforce-related purpose of the ONA as creating a network among stakeholders to address issues relating to, for example, professional licensure, language barriers, and improving access to economic development grants.

Minnesota’s ONA also will continue collaborating with on-the-ground partners such as the Neighborhood Development Center, a Twin Cities-based operation whose services include entrepreneur training and business incubators, and “ethnic councils” that provide supports for specific demographic groups.

“I want [the ONA] to have this really comprehensive understanding of the collective needs of our immigrant and refugee communities rather than just understanding what are the very specific needs of the Afghan community, or of the Ukrainian community, or the Hmong community,” Feist says.

“What I see this office doing is taking a lot of efforts that are going on at the city level, at the ethnic council level, at the charitable level, and bringing all of those threads together and creating a systematic way forward.”

“What I see this office doing is taking a lot of efforts that are going on at the city level, at the ethnic council level, at the charitable level, and bringing all of those threads together and creating a systematic way forward.”

Saskatchewan seeks more control of process

North of the U.S.-Canada border, provincial leaders are seeking greater autonomy over management of parts of that country’s immigrant system, a change being sought to help them address workforce challenges.

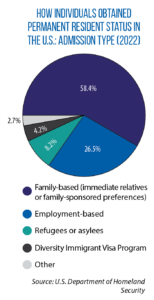

In terms of skilled-worker immigration, there currently are two pathways to obtain permanent resident status in Canada beyond the federal Express Entry route.

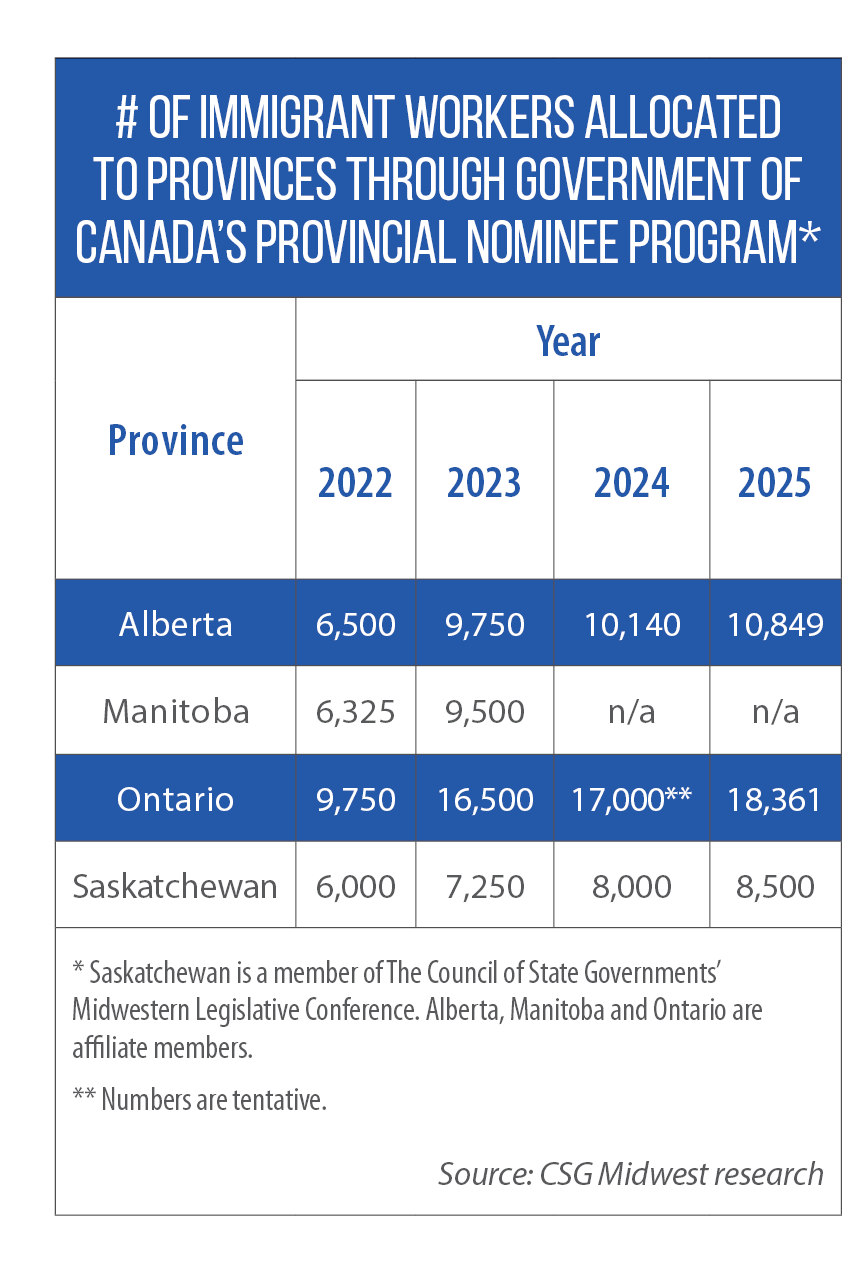

One of them is the Provincial Nominee Program (PNP), under which provinces are allotted a certain number of immigrants they can nominate for visas in a single year. In this system, applicants earn points based on their language abilities, previous job experiences, postsecondary education, available finances and other factors.

Qualified nominees with high enough scores are then eligible to have their names selected in draws throughout the year.

Another point of entry is immigrating through Québec, which has a system separate from the PNP and sole responsibility for the selection of “economic immigrants” (those who aren’t refugees or sponsored by a family) destined to that province.

In July 2022, a group of immigration-related ministers from Alberta, Manitoba, Ontario and Saskatchewan sent a letter to Canada’s Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship seeking changes to the current system.

“Provinces best know the needs of their local economies,” the letter said, noting the challenge of addressing “unprecedented labour shortages.” “We need the flexibility to respond to the rapidly evolving needs of specific areas and communities, with a flexible system that we can adapt to changing economic and humanitarian needs.”

In Saskatchewan, the province’s proposed Immigration Accord, modeled in part after Québec’s existing system, calls for an agreement with the Government of Canada that would allow for a greater number of immigrant nominees. That number would be based on the province’s population as a percentage of the whole country, and allow Saskatchewan to exceed this total by 5 percent “for demographic reasons.”

Also under the proposed accord, Saskatchewan would gain sole authority over the selection of economic immigrants to the province, while still recognizing Canada’s authority to determine foreign admission standards and maintaining a shared commitment to reuniting families and promoting multiculturalism.

Saskatchewan leaders said earlier this year that they were continuing to negotiate with the Canadian government over the proposed accord. They also hailed the federal government’s decision to increase Saskatchewan’s allotment of immigrant nominees via the current PNP. That number will reach 8,500 by 2025, an increase of 42 percent from three years earlier.

“Saskatchewan is seeing record-high population growth numbers, and immigration to the province has played a significant role in that,” Saskatchewan Immigration and Career Training Minister Jeremy Harrison said in March.

More recently, the CBC reported that the province was launching a pilot program that will reserve 10 percent of its PNP nominations for applicants from eight specific countries — seven European states (the Czech Republic, Germany, Ireland, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia, and Ukraine) and India.

Immigrants from these countries are most likely to retain permanent residency and stay in Saskatchewan over the long term, provincial officials said. Critics argue this policy will diminish the chances of entry for individuals from non-select countries and harkens back to a restrictive, pre-1967 approach to immigration.

New law accelerates credentialing process

Saskatchewan, meanwhile, also has been changing some of its own, province-specific policies.

A workforce development bill passed last year by the Saskatchewan Legislative Assembly (Bill 81) includes provisions to simplify and accelerate the credentialing process for skilled workers relocating to Saskatchewan from other provinces or countries.

By reducing barriers that prevent new arrivals from working in their profession, Government of Saskatchewan officials told CSG Midwest, the province can help “maximize the benefits of immigration.” Part of the province’s new efforts include creation of a Labour Mobility and Fair Registration Practices Office, which officials say “will provide navigation and financial support to newcomers looking to work in regulated occupations.” Additionally, the office will work with professional regulatory bodies “to speed up and streamline foreign qualification recognition pathways.”

Canada providing visas for tech jobs

Efforts to boost foreign immigration in order to address workforce shortages in high-demand sectors is also being seen on the federal level in Canada. This past June, the country introduced a visa program known as the the Tech Talent Strategy in an effort to poach from the United States H-1B immigrants working in STEM fields.

The success of this program was recently featured by CNBC.

Julia Gelatt, a researcher at the Migration Policy Institute, explains this targeted program is in recognition of how certain immigrant groups in the U.S., particularly those from China and India, face “untenable backlogs in order to get permanent residence.”

“Canada is not offering them permanent residence, but Canada does have many ways for temporary workers to adjust to permanent status over time, whereas in the U.S. we have kind of a temporary system and a permanent system, and they weren’t designed to work together,” explains Gelatt.

This disconnect between the economic benefits of long-term and short-term immigration harken to another angle of immigration policy explored by the MPI — the potential overreliance countries and states have on foreign labor to close labor gaps.

Increased immigration as a short-term solution

In the MPI policy brief “What Role Can Immigration Play in Addressing Current and Future Labor Shortages?” published in April, author Kate Hooper presents the argument that it’s important for policymakers to understand what exactly constitutes a true, long-term workforce shortage, and that an overreliance on immigrant labor — particularly for jobs susceptible to automation — could result in unintended, increased unemployment rates in the future.

“In the United States, immigrants make up a disproportionate share of the workforce in key industries such as health care, agriculture, logistics, and retail, working in jobs across the skill spectrum,” writes Hooper.

“Relying on immigration to address shortages can lead to employers and governments putting off necessary investments, such as upskilling local workers for hard-to-fill or newly emerging jobs or improving productivity in sectors through mechanization and restructuring jobs.”

Both Hooper and Gelatt raise the point that widespread automation will not necessarily take hold in every industry sector in the near future, but that the possibility exists.

“I’m from Wisconsin, so I think about the dairy industry,” says Gelatt. “There are severe challenges in recruiting workers for the dairy industry, and that’s a place where the H-2A, our existing farm worker visa, isn’t available. And so dairy farmers have more recently turned to milking machines.”

“There’s more use of robots in the service industry [in countries like Japan] than there is in the United States because we have a lot of people who are willing to accept the wages that employers are willing to pay for those jobs,” she adds. “The presence of lots of immigrants in the United States who lack a college education means that we might be slower to automate some of those jobs that are more susceptible to automation, but at the same time, if it really is cheaper to invest in a machine than to continue to employ workers, even at the depressed wages that might exist because of immigration, that that could happen.”

Recognizing that greater economic flexibility and international competition also means more and more immigrants no longer feel obligated to stay in low-paying professions, the April policy brief suggests that immigration workforce solutions should embrace such flexibility.

This includes attracting candidates adept at using greater critical thinking skills for jobs less prone to automation, creating non-employer sponsored visas for high-skilled applicants, and creating “sector work permits” that allow immigrants to work in a particular industry field while not being tied to a single employer and thus helping to avoid exploitative working conditions.