Rates of chronic absenteeism are much higher than pre-pandemic levels; Indiana is among the states with a new law to address it

The long-term consequences for habitually missing school are numerous.

A student falls behind in reading comprehension during the pivotal early grades. Social-emotional development is diminished. And it becomes more common that a young person will not graduate on time or will drop out of school entirely.

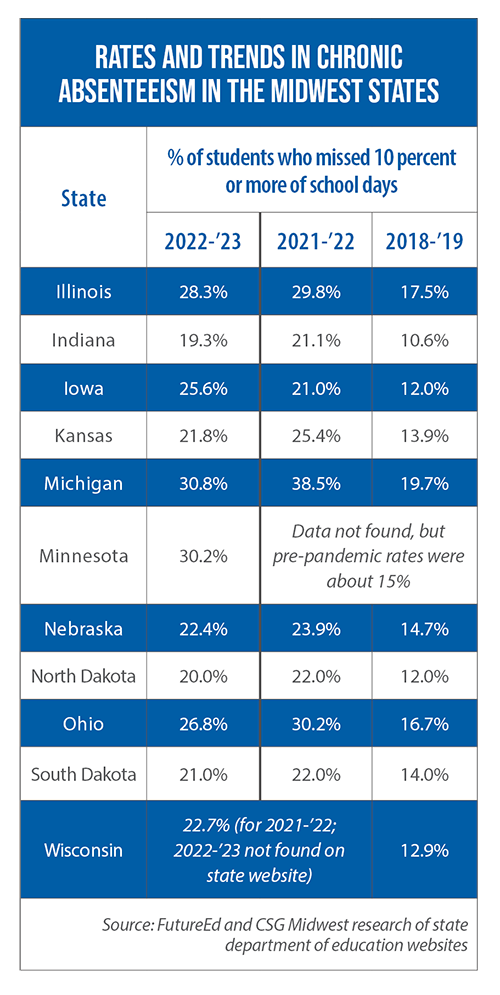

In every Midwestern state, students are considered “chronically absent” if they miss 10 percent or more of the school year. This attendance problem worsened during the pandemic, and despite a return to in-person learning, rates of chronic absenteeism have yet to drop back down to pre-pandemic levels (see table for the Midwest).

Getting to the root causes

The nonprofit initiative Attendance Works categorizes the root causes of chronic absenteeism, placing them into one of four “buckets” (see graphic).

A student’s socioeconomic status can play a role in how many buckets are filled or the severity of the contributing factors that keep them from school — for example, housing insecurity, community violence or a lack of transportation.

But Attendance Works founder and executive director Hedy Chang adds that all young people are susceptible to having attendance impediments, to becoming disengaged with learning, and to possessing a negative association with the school environment.

“Aspects of the buckets changed during the pandemic,” Chang says.

“[Chronic absenteeism is] deeper and more pervasive in some ways among economically challenged communities. And there are more kids who are not economically challenged who are chronically absent than ever before.”

To turn around this trend, Chang stresses the importance of collecting good, timely data. She points to Connecticut as an example of this approach.

During the pandemic, that state not only adopted a universal definition for both in-person and virtual-learning attendance, but also began collecting attendance data monthly instead of annually.

This new trove of data, plus a commitment to making attendance rates public and promptly addressing any reporting inaccuracies, led to the creation of a home-visit model: the Learner Engagement and Attendance Program.

Visits began being made to the homes of a targeted set of chronically absent students in order to make direct connections with students and their families. Though chronic absenteeism in Connecticut remains high, these interventions helped to reduce rates by almost 3 percentage points between academic years 2022 and 2023.

The visits also have led to student placements in after-school, summer school and other learning-enrichment programs.

Chang has said, too, that these visits “improved family-school relationships, increased feelings of belonging, improved access to resources, and [led to] greater gratitude and appreciation” — all of which can improve attendance.

Indiana’s new interventions

Tackling chronic absenteeism was a top priority this year for Indiana lawmakers.

“Almost one in five Indiana students were chronically absent last year,” Sen. Linda Rogers says. “There were 547 schools where a quarter of the students were chronically absent, and 84 schools where half of the students were chronically absent.”

She was a co-sponsor of this year’s SB 282. Signed into law in March, it requires school districts to develop truancy prevention plans while also creating a framework for future state action.

“Absent students,” those missing five days of school within a 10-week span, will be provided with wraparound services to increase the likelihood of attendance and be referred to counseling or mentoring.

The parents/guardians of “absent students” will be required to take part in a school-initiated conference about the attendance problem. They also will be informed about the legal consequences of a student becoming habitually truant, and may be expected to attend counseling or mentoring with their child.

Students with unique attendance barriers — for example, foster care placement, homelessness and life-threatening illness — will receive additional services.

SB 282 also gives Indiana’s attendance officer (who is appointed by the state secretary of education) a new responsibility: regularly collect ideas and recommendations for legislative action from local school officials, and then provide a yearly report to the General Assembly.

Initially, the bill included a more punitive approach: authorizing juvenile courts to impose civil fines of up to $1,000 on the parents/guardians of habitually truant students.

After receiving feedback from various stakeholders, Rogers says, she and her colleagues amended the bill with a “softer approach.”

Chang says she understands and believes in the idea of holding students and families accountable. But she also suggests that lawmakers be wary of punitive approaches, which often don’t take into account the root causes of absenteeism and also can lead to inequitable treatment.

“You have two kids who are both sick: One kid has a doctor and brings in a doctor’s note, and the other kid doesn’t have access to health care and doesn’t bring a note,” she says. “The kid without the note is going to have the unexcused absence.”

Chang also points to a 2020 report by The Council of State Governments Justice Center on findings from South Carolina. In that state, the CSG study found, the involvement of the juvenile justice system for chronically absent students resulted in even worse attendance rates.

Financial ‘nudge’?

This year in Ohio, lawmakers have been debating the efficacy of a new way to boost attendance — financial incentives.

Under HB 348, the state would establish two pilot programs. The first would provide cash transfers ranging from $25 to $500 to a select group of kindergarten and ninth-grade families whose students maintain an attendance rate of at least 90 percent within a two-week, quarterly or yearlong period.

The second pilot program would award selected students $250 for graduating high school, and an additional $250 for maintaining a grade-point average of 3.0.

“My seventh-grade social studies teacher always told us, ‘Always remember this, kids: Money isn’t everything, but it’s way ahead of whatever’s in second place,’ “ Rep. Bill Seitz, one of the bill’s two primary sponsors, said during a committee hearing on previous incentives that schools have offered to improve attendance.

The attendance-specific pilot program would target schools with the highest quartile of chronic absenteeism in Ohio.

For his committee hearing witness slip, the bill’s other main sponsor, Rep. Dani Isaacsohn, referenced a 2016 study by the National Bureau of Economic Research that evaluated the relationship between cash transfers and attendance and academic performance among a group of freshmen in Chicago Heights, Ill. One of the conclusions of that study was that cash rewards were the most effective, at least in the short term, for students just below the performance measure baseline.

Isaacsohn explains one of the variables this pilot would evaluate, if the bill passes, is the extent of cash as an input.

“[What we want to test is] how many people there are who could be nudged or who could be moved with a cash incentive to shift toward a culture of daily and regular attendance,” he says.