Issue Brief: Overview of recent laws and investments to combat teacher shortages

New CSG Midwest study focuses on legislative actions from 2021 to 2023

“State Efforts to Combat Teacher Shortages: A look at new laws and investments in the Midwest” ~ PDF

Legislative Tracker: 2023-2024 Bills and Laws

Legislative Tracker: 2023 Enacted Laws

Introduction

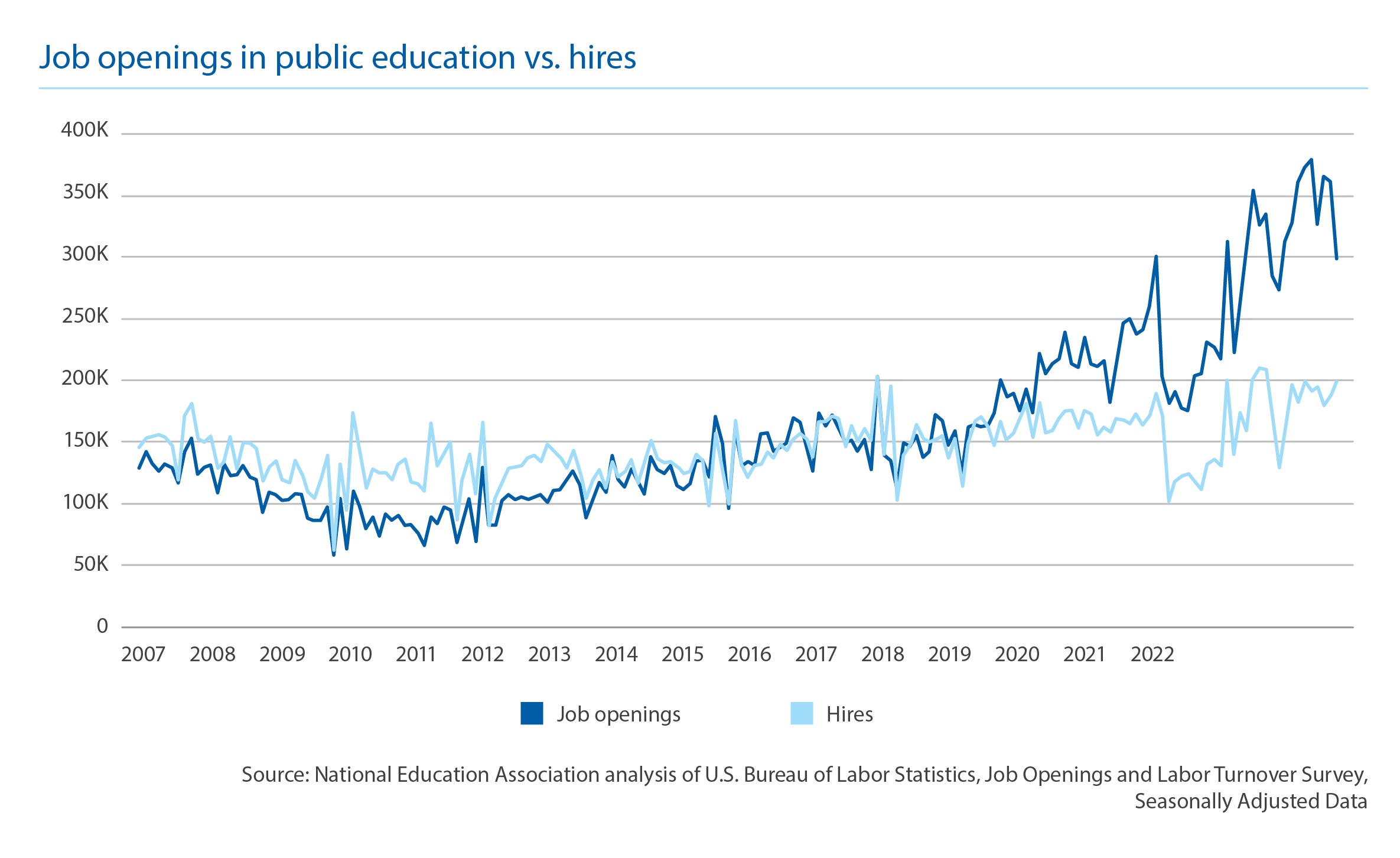

Interest in being a classroom teacher has waned in recent years, and state policymakers are having to confront how best to incentivize qualified applicants to fill long-existing vacancies, keep current educators in the classroom, and encourage more people to enter the profession.

Whether it includes adopting licensure accommodations, offering financial aid, or providing upskilling opportunities, the tactics that Midwestern states are taking to recruit and retain educators are purposely multifaceted.

This issue brief showcases the myriad strategies Midwestern state legislatures and agencies have implemented in recent years, with a focus on the years 2021 through 2023. Among the ideas:

- New or expanded scholarship programs for prospective teachers;

- Loan forgiveness and bonuses for existing teachers;

- State-level changes in licensure requirements and teacher preparation programs;

- Targeted assistance for paraprofessionals to become licensed educators; and

- Help for school districts in expanding their pool of substitute teachers.

The challenges of teacher recruitment

Two years ago, researchers at Kansas State University and the University of Illinois examined the extent of the nationwide teacher shortage following the dramatic impact that the global pandemic had on the education labor market.

The study, “Is There a National Teacher Shortage? A Systematic Examination of Reports of Teacher Shortages in the United States,” identified “at least 36,000 vacant positions along with at least 163,000 positions being held by underqualified teachers.”

The numbers point to the need to attract more people to the profession, and then encourage them to stay.

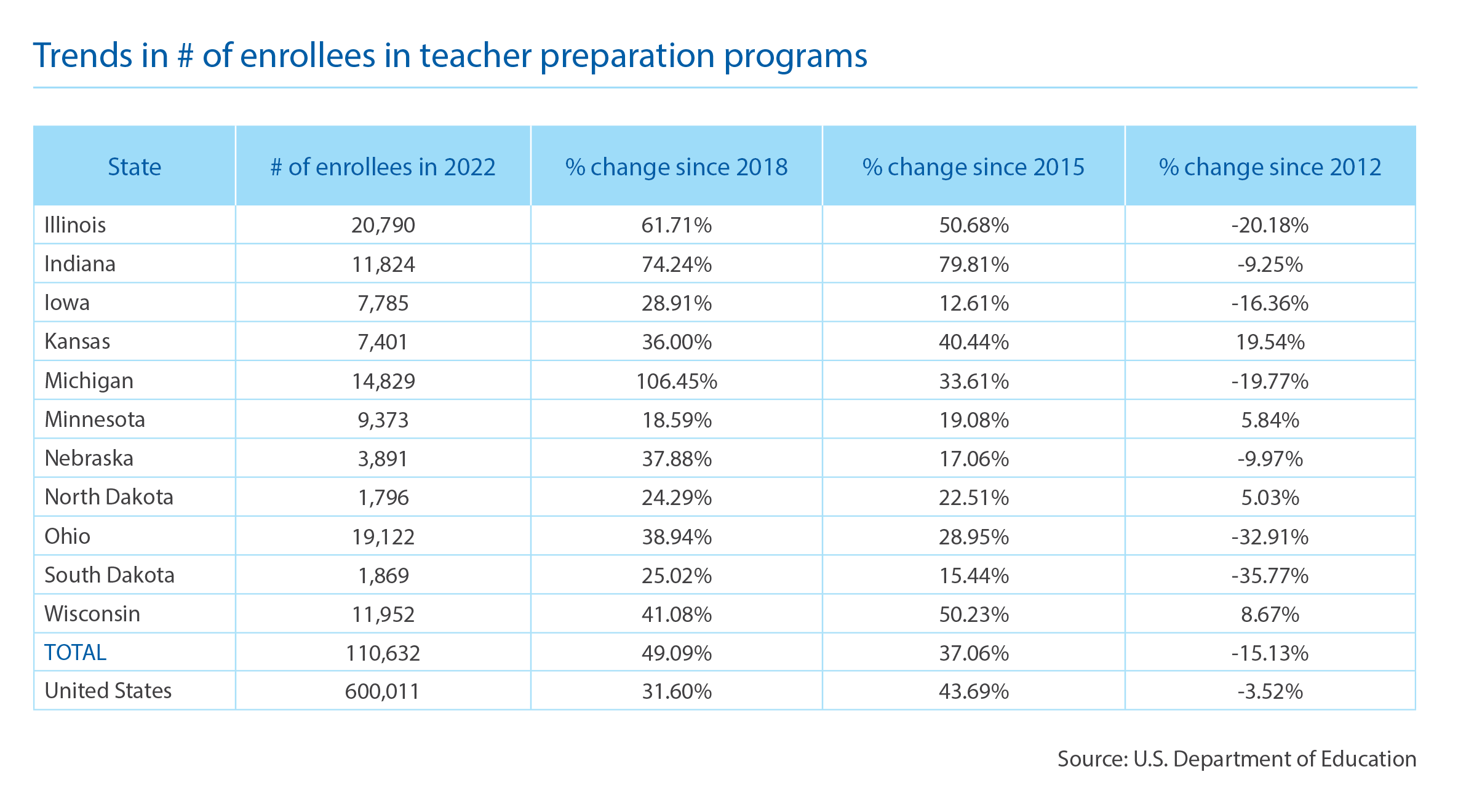

On that first indicator, the challenge became clear during the early part of the last decade, based on data reported annually by the U.S. Department of Education: Nationwide, the total number of enrollees in a teacher preparation program dropped by 33 percent between academic years 2012 and 2015.

Numbers have been going up since then, but as of 2022, there still were fewer individuals in teacher preparation programs than from a decade earlier. Across the 11-state Midwest, the trends look like this:

- 130,000 enrolled in teacher preparation programs in 2012;

- 81,000 in 2015; and

- 111,000 in 2022.

Another 2022 study, “The Rise and Fall of the Teaching Profession: Prestige, Interest, Preparation, and Satisfaction Over the Last Half Century,” takes a multi-generational view of the challenges of teacher recruitment.

In the early 1970s, around one in four college graduates had earned a degree in education. Steep declines in this rate occurred in subsequent years due to a mix of factors: inflation and stagnant wages, plus new career opportunities for women and people of color, who historically made up a disproportionate share of the nation’s teacher workforce.

The study’s authors credit a 1983 report by the National Commission on Excellence in Education (“A Nation at Risk: The Imperative for Educational Reform”) for renewing interest in the teaching profession and policymakers investing in it.

By 1987, the number of college graduates with a teaching degree had rebounded to around 12 percent and would remain constant — before dramatically dropping again in the 2010s following the Great Recession.

“By 2019, only 8.1% of B.A. and M.A. degree completers were education majors, a third of the rate from earlier decades,” the study found.

Other findings:

- “Interest in the teaching profession among high school seniors and college freshmen has fallen 50 percent since the 1990s, and 38 percent since 2010, reaching the lowest level in the last 50 years.”

- “Teachers’ job satisfaction is also at the lowest level in five decades, with the percentage of teachers who feel the stress of their job is worth it dropping from 81 percent to 42 percent in the last 15 years.”

- “Between 2018 and 2022, the percentage of parents who said they would like their children to be teachers dropped from an already low 46 percent to 37 percent.”

Insights from Illinois, Kansas surveys of educators

Getting a better handle on the modern teacher labor market, as well as the extent and impact of shortages, is among the goals of statewide surveys that recently have been done in states such as Illinois and Kansas.

Over the past seven years, the Illinois Association of Regional Superintendents of Schools has released an annual report documenting district struggles with finding teacher candidates. For the association’s 2022 survey, 79 percent of school districts indicated they were experiencing a teacher shortage problem. Forty-five percent of them reported that the shortages were worse than those experienced in the year prior.

Over the past seven years, the Illinois Association of Regional Superintendents of Schools has released an annual report documenting district struggles with finding teacher candidates. For the association’s 2022 survey, 79 percent of school districts indicated they were experiencing a teacher shortage problem. Forty-five percent of them reported that the shortages were worse than those experienced in the year prior.

During the 2022-23 school year, 30 percent of the posted teaching jobs in Illinois either went unfilled or were filled by under-qualified candidates — that was the highest rate ever documented by the association. Some of the hardest-to-fill positions were for elementary-grade, bilingual, gifted and computer science teachers. Across all regions — be it the Chicago area or Downstate Illinois — a majority of respondents reported their schools were not adequately staffed.

The Illinois superintendents cite several reasons for the difficulty in recruiting and retaining teachers. At the top of the list: overdemanding workloads, better compensation in other professions or districts, the political climate, and community perceptions of the teaching profession.

In 2021, several Kansas educator groups launched the Kansas Teacher Retention Initiative. For its second report, more than 24,000 Kansas educators were surveyed. Among the survey findings:

- Fifty-five percent of respondents were categorized as “disengaged” or “actively disengaged” based on their responses. This is up from 46 percent in the 2021 survey.

- Twenty-eight percent of respondents indicated they are more likely than not going to leave their current teaching role — either as the result of retirement or deciding to leave public education for other pursuits.

- Millennial teachers (ages 27 to 42 years old) and teachers who have been in the profession between four and 11 years reported being the least engaged about their profession.

- There is common dissatisfaction with society’s view of the teaching profession, the ability to request and secure a substitute teacher when a teacher absence occurs, and future salary growth potential.

The survey results in Illinois and Kansas lay out the challenges for states in trying to build teacher workforces, but they also point to signs of progress or hope.

For example, survey respondents in Illinois reported positive results from efforts to strengthen supports for student teachers and to help current teachers secure additional endorsements. The superintendents also said recent changes in state law have helped them address persistent shortages in substitute teachers.

In Kansas, the likelihood of turnover for new teachers (those in their first three years) dropped by four percentage points between surveys. In addition, respondents expressed common satisfaction with the relationship they have with their colleagues at school, the opportunity to work with diverse student populations, and their teacher-principal relationship.

Teacher surveys such as the ones in Illinois and Kansas can help state policymakers make better-informed decisions about how to bolster their teacher workforces.

Based on recent legislative actions, states are seeing value in providing additional financial incentives, reforming their licensure systems, and providing new “upskilling” opportunities among non-licensed school employees.

Changes in teacher licensure

One of the most common strategies used by state legislatures in the Midwest has been to provide more flexibility and options through their respective teacher licensure requirements or teacher preparation courseloads.

The goal of these changes has been to encourage individuals to enter or stay in the teaching profession.

Some of these accommodations come in the form of creating alternative licensing pathways for new and veteran educators alike.

- SB 3988, passed in Illinois in 2022, allows 18-year-olds to be issued a paraprofessional endorsement if they are working with students in prekindergarten through eighth grade.

- That same year, Ohio legislators passed HB 554, which authorizes the State Board of Education to issue a nonrenewable, two-year teaching license to any person with an expired teacher’s license who has no disciplinary issues on record. The new license is for teaching the same grades and subject area endorsed under the previous license. Individuals can then earn a permanent license if they complete the required educational coursework.

Another licensure option: simplify the process for prospective teachers who have recently relocated to the state.

- Under Illinois’ SB 2043 (2021), teachers trained in other states and countries no longer need to demonstrate proficiency of the English language in order to obtain a teaching license.

- Also in 2021, the Nebraska Legislature passed LB 528 and LB 389. LB 528 gives the state commissioner of education the authority to grant a temporary teaching certificate to anyone who has completed a teacher preparation program and who has a license from another state. This temporary certificate can also be awarded to anyone who has earned a postsecondary degree and has passed a basic skills test. The second law, LB 389, authorizes the issuance of teaching certificates to military spouses who have had a teaching license from another state for at least one year.

The Nebraska Legislature made additional changes in 2023. LB 705 removes a basic skills test as a requirement for teacher candidates, but keeps in place a requirement for applicants to pass relevant content tests. In addition, individuals who have a bachelor’s degree and who were certified through an alternative teacher pathway can obtain Nebraska certification if they agree to participate in a clinical experience at a school district for one semester.

Under Illinois’ SB 808, passed in 2021, teacher candidates no longer need to videotape themselves facilitating a classroom lesson during their semester of student teaching as part of a previous requirement under the Education Teacher Performance Assessment (edTPA).

And in 2023, Kansas lawmakers adopted SB 66, which authorizes the state to join the Interstate Teacher Mobility Compact. According to The Council of State Governments’ National Center for Interstate Compacts, this compact allows “teachers to use an eligible license held in a compact member state to be granted an equivalent license in another compact member state, lowering barriers to teacher mobility and getting teachers back into the classroom more seamlessly.”

Teacher mentorships

In recognition of how invaluable mentoring opportunities can be for newer teachers, a number of Midwestern states — particularly at the state education agency level — provide opportunities and resources that help novice educators feel better supported.

The goal is to improve retention rates among teachers new to the profession.

- In Iowa, the State Department of Education operates the Teacher Leadership and Compensation System, a program established and funded by the Legislature. According to the department’s website, “Through the system, teacher leaders take on extra responsibilities, including helping colleagues analyze data and fine-tune instructional strategies as well as coaching and co-teaching.” In addition to paying for teacher professional development opportunities, TLC funds also go toward supplementing the salaries of veteran teachers who take on various leadership roles. The goal for participating school districts is to have at least 25 percent of their teacher workforce serving as teacher leaders.

- The Illinois State Board of Education partners with the state chapters of the National Education Association and the National Federation of Teachers to pair teachers in their first three years with in-school mentors and virtual instructional coaches. In addition, participants receive a $500 stipend and gain access to an online database of teaching resources.

- In South Dakota, the Department of Education offers a two-year mentoring program for teachers in their first or second year of teaching. Selected participants are paired with a veteran teacher mentor who has been in the classroom for at least five years to observe their instructional style and offer coaching advice. New teachers also learn through attending webinars and a summer academy retreat that hosts teachers from across the state. Participating teacher mentors earn an annual stipend of $1,500.

State-funded scholarships and loan forgiveness

Given the high costs of college, and often relatively low starting pay in the profession, several states are bolstering financial assistance for prospective teachers.

- Kansas’ SB 66 expanded an existing, last-dollar-style scholarship program that helps teacher candidates as well as others pursuing degrees in high-demand professions. The income-based Kansas Promise Scholarship can be used in community colleges, technical colleges, and certain private institutions. It can be used for up to 68 credit hours of coursework or $20,000 of school costs.

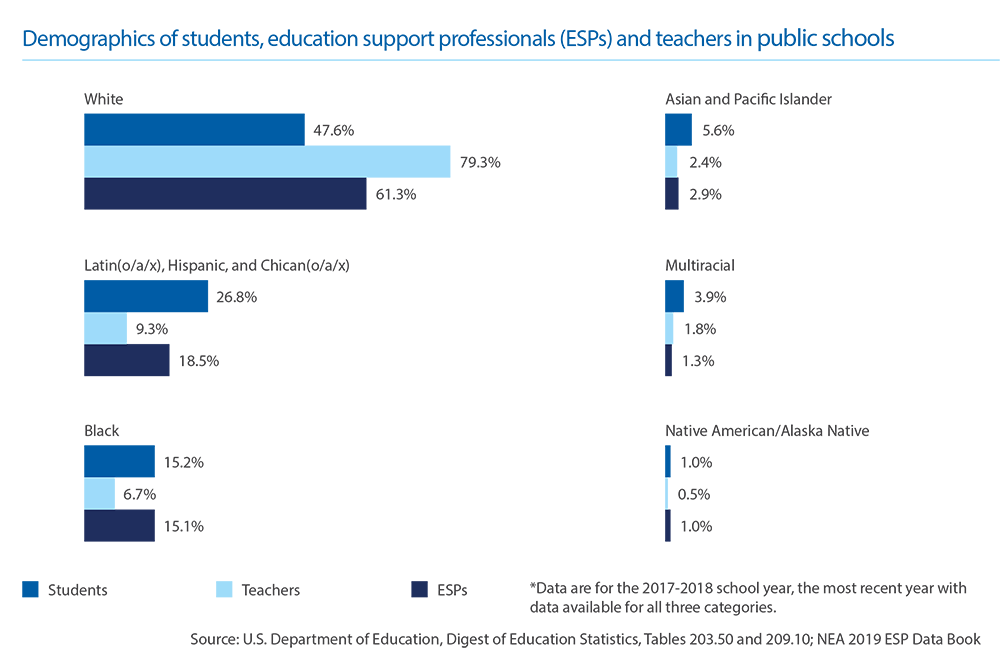

- In Minnesota, a scholarship program (HF 7 of 2021) is focused on recruiting a more diverse pool of teacher candidates. The Aspiring Teachers of Color Scholarship Pilot Program supports undergraduate and graduate teacher candidates who are American Indian or persons of color. Total financial aid is limited to $25,000, with a maximum allotment of $10,000 in a single year. HF 7 also provides stipends for low-income, underrepresented student teachers and low-income student teachers who intend to teach in a rural area or a high-demand subject area. Additionally, loan-repayment opportunities are made available for student teachers from groups that are ethnically and racially underrepresented in the teaching profession. Loan repayments also can go to student teachers who intend to work in either a rural district or a high-need subject area.

- Michigan has for years committed financial resources to the state’s MI Future Educator Fellowship. Under the program, certain college juniors with a grade-point average of at least 3.0 are eligible to apply for this $10,000 scholarship, which can go toward tuition and fees while they earn a degree in teaching. Recipients commit to teach at a Michigan school upon graduation for a determined number of years, based on how long they receive fellowship funding. For example, one year of fellowship funding equates to a commitment to teach in Michigan for at least three years.

Upskilling and expanding the pool of teachers

States in the Midwest also have been investing more in programs that target assistance for individuals who are already in the education profession, but who are not licensed teachers. This state support allows for the “upskilling” of paraprofessionals by removing financial barriers.

- Under Nebraska’s LB 705, paraprofessionals and individuals who have completed two years of college can receive a temporary certificate to teach full-time. In addition, paraprofessionals wanting to obtain a teaching permit can participate in a yearlong apprenticeship experience. For this program, the Legislature directed a transfer of $1 million from the state’s newly established Education Future Fund.

- In North Dakota, state lawmakers in 2023 passed SB 2032, which appropriates $3 million in grants for paraprofessionals who are in a program to become a licensed teacher.

- In South Dakota, the new Teacher Apprenticeship Pathway helps teacher aides and paraprofessionals achieve full teaching degrees. This two-year program, which had an inaugural class of 90 participants, offers online evening classes and culminates with a student teaching experience. The cost for participants is kept to a minimum.

Lawmakers in Indiana and Kansas provide financial incentives for adult learners who possess no previous background in education, but who are interested in joining the teaching profession.

- Indiana’s HB 1528 (2023) establishes a one-time scholarship of up to $10,000 to applicants enrolled in a transition-to-teaching program. Qualified applicants must possess a bachelor’s degree and agree to teach for five years after graduation.

- The Kansas Adult Learner Grant program (SB 123 of 2023) provides up to $3,000 per semester to qualified adult learners pursuing a postsecondary degree in certain subject areas, including general education and early-childhood education and development.

Financial assistance for veteran teachers

Other financial assistance-based strategies enacted by Midwestern states include loan forgiveness and bonuses for existing teachers.

- Nebraska’s LB 1218 (2022) created the Teach in Nebraska Today Program. It offers student loan repayment assistance for full-time teachers — up to $5,000 per year for up to five years. The overall statewide allotment for this program is up to $5 million in any fiscal year. In addition, LB 705 (2023) authorizes some money from the newly created Education Future Fund to go toward bonuses and grants for newer teachers. At the start of their second, fourth, and sixth years in the classroom, teachers can apply for a $2,500 bonus. Those with certification in a high-need area are eligible for a one-time grant of $5,000.

- Come Teach in Minnesota (the result of HF 2, passed during a 2021 special session) prioritizes the hiring of teachers from other states and countries who are either American Indian or persons of color. Those selected must belong to a racial or ethnic group that is underrepresented among the other teachers in the district where they are hired. Schools can offer a bonus ranging from $2,500 to $5,000 to a teacher who meets these eligibility requirements. Schools can also offer a bonus ranging between $4,000 and $8,000 to those who meet the aforementioned eligibility requirements and have a license in a high-need subject area. Selected teachers receive half the bonus when they start, and the other half either after four years of teaching or after demonstrating classroom effectiveness. The same Minnesota law also requires schools to develop mentorship programs for new teachers and provides funding for “grow your own” programs (for example, helping paraprofessionals become teachers) that emphasize diverse hires.

- Illinois lawmakers adopted two bills in 2023 that reward educators who are certified by the National Board for Professional Teaching Standards. Through HB 3801, $4,000 bonuses are awarded for up to two consecutive years to National Board-certified teachers employed at a “hard-to-staff school” — defined as a school where at least 30 percent of students are low-income. HB 1291 increases the annual pay incentive cap from $1,500 a year to $2,250 for National Board-certified teachers who engage in 45 hours of professional development mentoring.

Flexibility for substitute teachers

Lawmakers also are removing licensing and other hurdles to increase the pool of prospective substitute teachers for school districts.

- In Illinois, SB 3907 (2022) allows a substitute teacher to be in the same classroom for longer stretches of time in place of an absent teacher — up to 15 consecutive days, compared to five consecutive days under the previous law. HB 3442 (2023) goes even further and allows for a substitute teacher filling in for a vacant teaching position to teach for a period of 90 days.

- Wisconsin’s AB 975 (2022) expanded the eligibility of individuals who can receive a substitute teacher permit from the state. Under the law, someone who is at least 20 years old, is enrolled in a teacher preparatory program, and has completed at least 15 hours of classroom observation can be a substitute teacher.

- Illinois’ HB 4798 (2022) allows a teacher candidate who has earned at least 90 hours of college credit to obtain a substitute teacher license.

- Ohio’s HB 583 (2022) temporarily permitted the issuance of substitute teaching licenses to people who don’t possess a postsecondary degree; this provision was only in place for academic years 2022 through 2024.

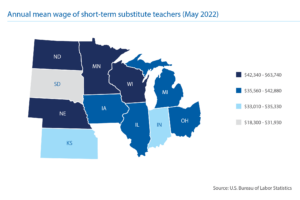

- In Minnesota, HF 2497 (2023) created the Short-Call Substitute Teacher Pilot Program. This two-year licensing avenue is for individuals who possess a high school equivalency degree or the equivalent of an associate degree. They must undergo a background check and take substitute-teacher training.

State reports and teacher pay

In recognition of how paramount teacher pay is to whether many educators enter and/or stay in the profession, at least one state in the Midwest formally tracks this data on an ongoing basis.

The South Dakota Teacher Compensation Review Board was established in state statute nearly a decade ago and releases a report every two years. One of its metrics is to compare actual average teacher salaries against the state’s established “target teacher salary.” That target is set by the Legislature and is based on several factors, including the amount of state aid, inflationary changes, and the state’s education finance formula.

The actual average salary was a little more than $51,000 during the 2022-23 school year, more than $4,000 below the target.

The “target teacher salary” increased 8.45 percent between academic years 2017 and 2022. Actual salaries rose 7.69 percent over this time.

In addition to assessing in-state salary trends, the board compares teacher wages in South Dakota to other states in the region. Despite continued salary increases, South Dakota still lags behind in average teacher salaries compared to neighboring Montana, North Dakota, Nebraska, Iowa, Minnesota and Wyoming. In 2022, even if the average in-state teacher salary had met the target salary of $52,600, South Dakota would still have had the 47th lowest average teacher salary level in the country.

To better understand the scale of teacher salaries going forward, the board included the following recommendations in its 2023 report:

- Direct the South Dakota Department of Education to craft an updated teacher salary/compensation accountability model that enhances average teacher salaries at the district and state levels.

- Recommend that the legislative and executive branches carefully monitor the ongoing impact of inflation when setting changes in the state education finance formula.

Conclusion

Attracting new and former educators to the classroom is only part of the solution. The real test is being able to keep teachers wanting to return for a new school year.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, one of the most prominent factors that influences an educator’s decision to leave a school or the profession altogether is salary. According to a 2021 report by the Institute of Education Sciences, a survey of thousands of former Michigan educators found that 33 percent of respondents were no longer teaching because of a want for a higher salary.

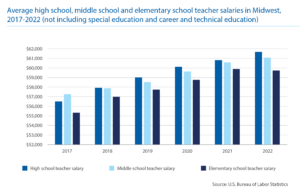

Available national and state data (such as the information being collected and reported by South Dakota) show that average teacher salaries are increasing on a yearly basis. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, in May 2017, the average teacher salary among primary- and secondary-school teachers in the Midwest (excluding special education and career and technology education instructors) was over $56,000 a year. By May 2022, this average annual salary had increased to nearly $61,000.

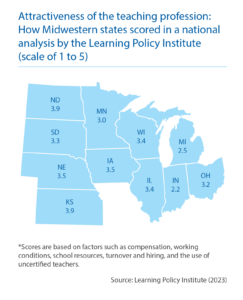

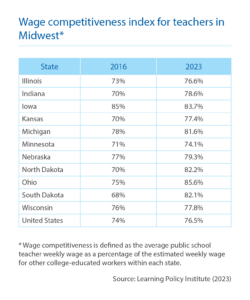

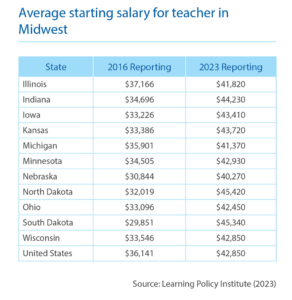

The starting salary for teachers also has increased. In 2016, the Learning Policy Institute reported (based on data from 2012 through 2014) that the average starting salary in the Midwestern states was about $33,000. The average “wage competitiveness index” for the Midwest — which compares the average public school teacher salary against the salaries of non-teachers with a similar level of educational attainment — was 73.9 percent.

In 2023, the Learning Policy Institute reported that this gap had closed somewhat. Based on data from 2017 through 2022, the average starting salary for teachers in Midwestern states had grown to more than $43,000, with an average wage competitiveness index of 79.9 percent.

Despite this growth, groups such as the National Education Association argue national salary increases are being offset by higher living costs.

When adjusted for inflation, the NEA found the national average starting salary for teachers in 2022 was $4,552 below 2009 levels.

As was pointed out in an October 2023 report by the education group Advance Illinois — a report that found the state was experiencing an increase in teacher and paraprofessional hires, a greater supply in principals, and an increase in diverse teacher hires — the work is not yet done and further improvements can be made.

“It is critical that we make every effort to understand what is working, and what is not, and that we be prepared to deploy additional state resources to continue programs with a promising or proven track record.”